by Matthew L. Kroll

To say that readers need a roadmap to guide them through the prolific, often perplexing work of American poet Charles Olson (1910–1970) perhaps edges too close to cliché — the kind of bland and general statement which Charles Olson successfully and adamantly avoided throughout his career. But it is, I think, true. As is the fact Charles Olson spent much of his career making ‘maps,’ of one kind or another. Olson’s interest in cartography and archival maps, and his almost ontological understanding of geography, manifest his acute thinking of and through space and place. But Olson also created ‘maps’ of thought across his writings and lectures: uncovering and connecting people, places, languages and literatures across various eras of human history, including his own. The work of the Olson scholar involves tracing these ‘thought-maps,’ if you will, to the benefit of readers and students of Olson.

To add clarity and depth to the scholarly exploration of Olson’s idiosyncratic thinking and writing, a researcher will surely benefit from the vast and varied Olson material available at the Archives and Special Collections in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut. Thankfully, this carefully curated collection has a detailed finding aid, and the staff has a wealth of knowledge to further help visitors navigate the collection. But all that guidance could not fence me from the inevitable sense of disorientation I felt after my first day engaging with the Olson archives during my research trip.

Suffice to say, the breadth of Olson’s knowledge can make his readers’ head spin, leaving us grasping for a sense of direction. The archived material available in Storrs attests to the immense range of thinkers and writers of various fields and genres with which Olson engaged. The unpublished material there can help us fill in the gaps and make our own pathways through his dense thought. The Olson scholar must, I think, (paraphrasing his line) “find out for him-/herself” a way to orient oneself to Olson’s mind.[1] For my own research purposes, this has been to focus on Olson and early Greek thought.

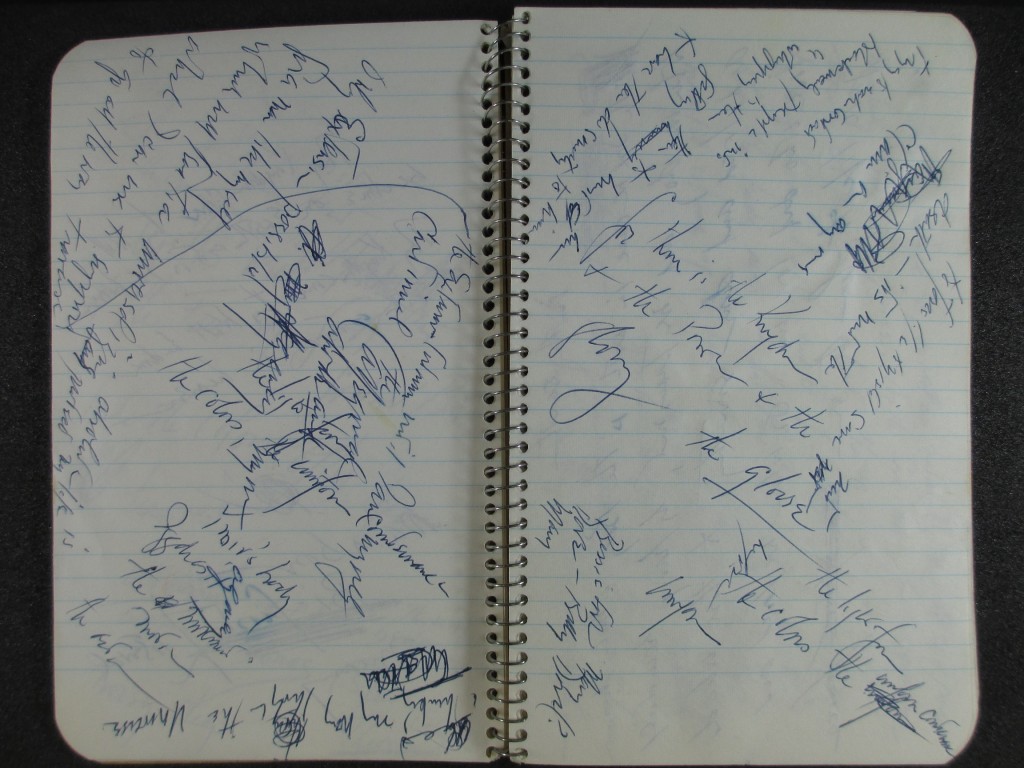

Before arriving in Storrs I was confident I had a good plan of research going in. Within only a few minutes of arriving at the Charles Olson Research Collection, however, I realized the most important, and unexpected, task of my week: orienting myself to Olson’s often unintelligible handwriting! The image below demonstrates both the difficulty in reading Olson’s handwriting, and offers us a glimpse of how his mind worked. Note the multiple directional orientations of his handwriting across these two pages from a notebook dated 11 November – 13 December, 1964 (Box 56, folder 103).

A dizzying experience, indeed. This image is particularly relevant here as it shows us Olson working through Whitehead’s concept of the ‘extensive continuum’ (from Process and Reality), essentially, the spatio-temporal extensiveness of the world. This is vintage Olson: working through a philosophical concept which is fundamental to how human beings orient themselves in the world, doing it with such freedom and instantaneous changes of direction that he actually writes along several different axes across the page.

A dizzying experience, indeed. This image is particularly relevant here as it shows us Olson working through Whitehead’s concept of the ‘extensive continuum’ (from Process and Reality), essentially, the spatio-temporal extensiveness of the world. This is vintage Olson: working through a philosophical concept which is fundamental to how human beings orient themselves in the world, doing it with such freedom and instantaneous changes of direction that he actually writes along several different axes across the page.

But for all the frustration readers and researchers may find in Olson— his layered and obscure allusions, his frequently challenging syntax, his penmanship—there are some constants in Olson’s writing, especially in his magnum opus, The Maximus Poems. Olson’s modern verse epic is populated with many historical and geographical explorations of his adopted hometown of Gloucester, MA. We see through Maximus’ (Olson’s?) eyes Stage Fort Park, Dogtown, the waters and islands off Cape Ann and its surrounding environs, the settlers and early inhabitants of the area, its fishermen, its modern inhabitants, its poets…we even get a sense for life inside his 28 Fort Square apartment and the very desk he enveloped with his physical and intellectual magnitude. The early published versions of each of the three volumes of Maximus featured maps on their covers, maps which would later feature as the first pages of the volumes in the collected edition (ed. George F. Butterick, 1983). This was not merely a decision by Olson and his publishers to add cover art to the Maximus volumes. These maps serve to orient the reader to the directions which the subsequent poetry will take: from Gloucester out to the sea; from Gloucester back through deep and mythological history; and finally from Gloucester toward the West.

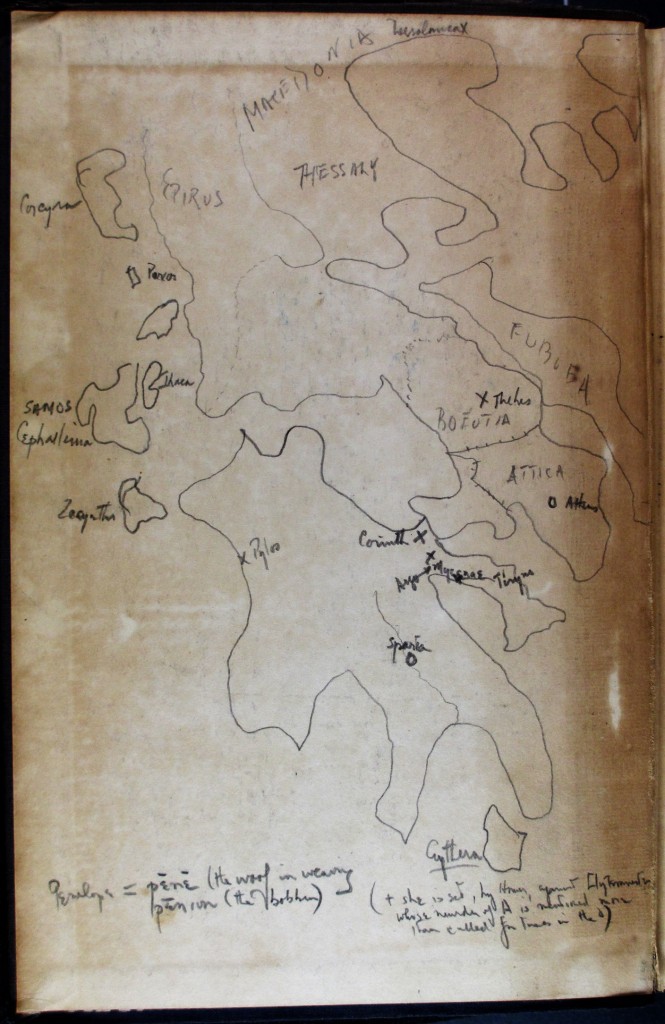

As I came to “find out for myself,” Olson himself mapped out the geography present in his favorite literature. I couldn’t help but laugh when I came across Olson’s Modern Library Edition (1935) of The Complete Works of Homer (Olson #710). Upon opening the front cover, I found a rather impressive freehand map of Greece which Olson drew in pencil.

As I came to “find out for myself,” Olson himself mapped out the geography present in his favorite literature. I couldn’t help but laugh when I came across Olson’s Modern Library Edition (1935) of The Complete Works of Homer (Olson #710). Upon opening the front cover, I found a rather impressive freehand map of Greece which Olson drew in pencil.

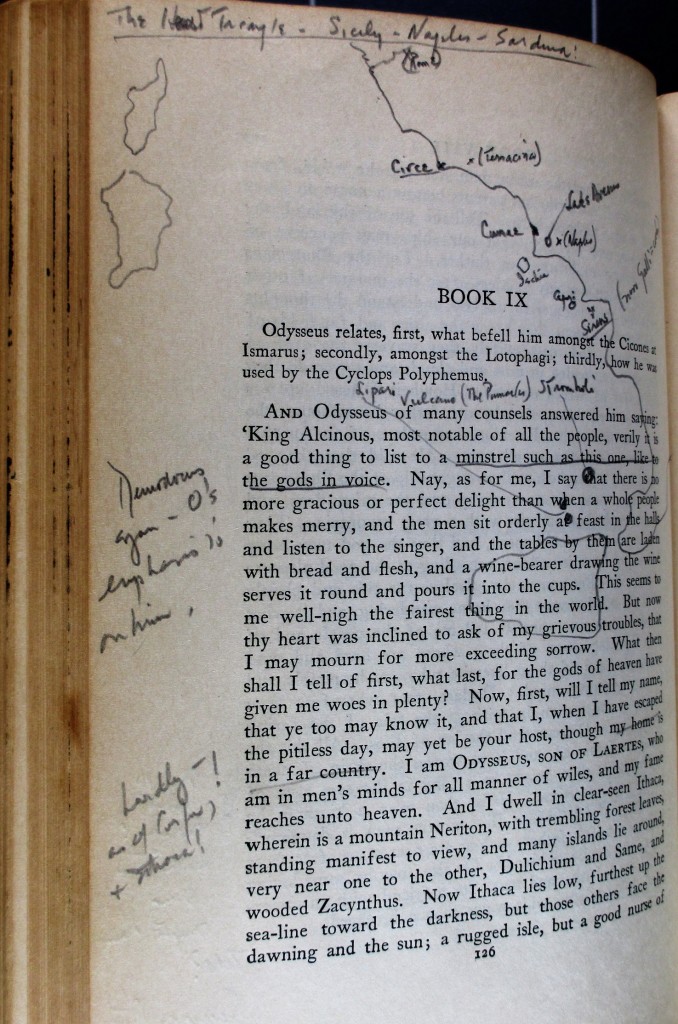

And later in the volume, on the first page of Book IX of The Odyssey, Olson again appears to be orienting himself to his reading, this time drawing a map of the west coast of Italy and the Tyrrhenian Sea. In his challenging fashion, the map is drawn right through the type!

This kind of interaction with his books is apparent throughout his library—as if Olson were responding to the text in his own hand in live time, creating a sort of interactive textual dialogue with whatever he was reading.

To conclude, Olson’s work is if nothing else rooted in place. It expresses particular locales with an energy that, for me at least, few poets have been able to transfer “all the way over to the…reader” as successfully as he does.[2] Fitting that a particular place exists—the University of Connecticut, where Olson taught briefly during what became the last year of his life—where Olson scholars can enact the very “prospecting” which his projective verse calls for, digging through his archived material to, hopefully, uncover some new place on the map of his thought—a new connectivity between his writing, his life, and the places, peoples, histories, and literatures which live in his work. Thanks to the generous support of a Strochlitz travel grant, I was able to at least begin the digging for my own research project. The Charles Olson Research Collection reinforced the aspect of his work which I think most gives it a unique vitality: it emanates a multiplicity of intense localities he’s “prospected”: places (physical, literary, and psychological) he inhabited, studied, and mapped.

Matthew Kroll is a PhD candidate in the Department of Philosophy at Purdue University working on his dissertation titled “The Poet and the Polis: Early Greek Thought in Charles Olson’s The Maximus Poems.” Mr. Kroll was awarded a 2015 Strochlitz Travel Grant from Archives and Special Collections at the University of Connecticut to support his ongoing research.

Notes:

[1] Olson’s line is in “A Later Note on Letter # 15” [Maximus, 249 (II.79)], in reference to Herodotus’ “concept of history”, ‘istorin, which Olson tells us “was a verb, to find out for yourself.” This understanding of the term is largely informed by J.A.K. Thomson’s The Art of the Logos (London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1935). Olson’s copy is in the Charles Olson Research Collection in Storrs, call no. Olson 450.

[2] “Projective Verse”, in Selected Writings, ed. Robert Creeley (New York: New Directions, 1966), p. 16.