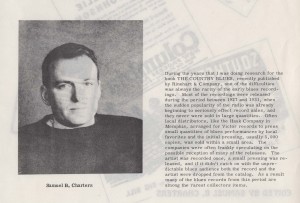

The series A Language of Song features the words of Samuel Charters and the recordings he produced as preserved in The Samuel and Ann Charters Archives of Blues and Vernacular African American Musical Culture at the University of Connecticut. The series is a tribute to the great Samuel Charters – poet, novelist, translator of Swedish poets, and renowned scholar of the blues, jazz, and musical culture of the African diaspora. Samuel Charters died on March 18 at the age of 85.

In the second post in the series, together with a personal remembrance by friend and UConn Libraries staff member Nicholas Eshelman, Mr. Charters describes his recording sessions in Louisiana with Cajun and Zydeco musicians including the great accordion player Nathan Abshire.

In the second post in the series, together with a personal remembrance by friend and UConn Libraries staff member Nicholas Eshelman, Mr. Charters describes his recording sessions in Louisiana with Cajun and Zydeco musicians including the great accordion player Nathan Abshire.

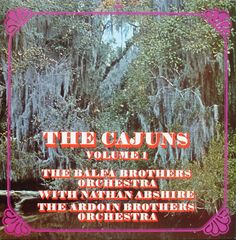

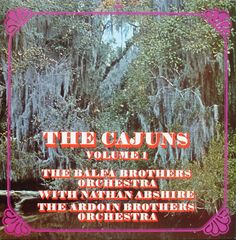

The sessions were released on a series of record albums including The Cajuns – Vol.1: Balfa Brothers Orchestra With Nathan Abshire (SNTF 643 Sonet, 1973). All of the recordings were done at the La Louisianne Studio, Lafayette, Louisiana. The Charters Archives holds the recordings and documents relating to the recordings, such as the studio log sheets.

Sonet Grammofon was interested in a wide range of American music, and over a period of several years I recorded a number of Cajun groups. The trips were usually in connection with other recordings that I was doing western Louisiana – often Rocking Dopsie – but also Bill Haley and the Comets, since I traveled to Nashville or Muscle Shoals for his albums. There was an initial double album set titled The Cajuns, and a number of individual Cajun albums, including a documentary of the famed Mamou Cajun Hour radio broadcasts from Fred’s Lounge on the main street of Mamou.

In December, 1972 I finished a session with Haley in Nashville and traveled on to Lafayette, Louisiana to do a broad documentation of the musical scene there. I worked with four groups, and rounded out the sessions with instrumental duets by talented accordion player Bessyl Duhon and a guitarist. The sessions captured exciting music that could not be duplicated, though I was able to record several other excellent groups a few years later. For this album the Balfa Brothers recorded with the great accordion player Nathan Abshire and the superb two violin team of Dewey Balfa and Merlin Fontenot, and on later recordings with the group neither Abshire or Fontenot took part. The Ardoin Brothers recorded with young Gus Ardoin playing the accordion, and he was tragically killed in a road accident only a few months later.

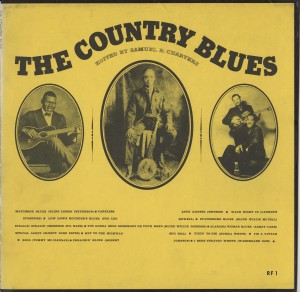

I first met Sam Charters in 2001 when my wife, Kristin, took a job at UConn that included curatorship of the Samuel and Ann Charters Archives of Blues and Vernacular African American Musical Culture. Meeting Sam was a big deal for me because my brothers and I had grown up listening to the records he produced, pouring over his liner notes and learning more from his great book, The Country Blues. This was in the 1970’s when finding the blues, jazz and folk LPs we loved in a small Pennsylvania town was nearly impossible, as was finding any good information on how the music came to be. This made every record we did scrounge up something precious, to be listened to over and over, so for this I felt I owed him a great debt and was more than a little nervous about meeting him.

I first met Sam Charters in 2001 when my wife, Kristin, took a job at UConn that included curatorship of the Samuel and Ann Charters Archives of Blues and Vernacular African American Musical Culture. Meeting Sam was a big deal for me because my brothers and I had grown up listening to the records he produced, pouring over his liner notes and learning more from his great book, The Country Blues. This was in the 1970’s when finding the blues, jazz and folk LPs we loved in a small Pennsylvania town was nearly impossible, as was finding any good information on how the music came to be. This made every record we did scrounge up something precious, to be listened to over and over, so for this I felt I owed him a great debt and was more than a little nervous about meeting him.

Sam and Ann had invited us to their home, and we were privileged for this to happen many more times over the years. I realized I could spend all evening asking him questions like “Did you know Gary Davis?” “What was Moe Asch / Dewey Balfa / John Fahey like?” And not just because he always graciously answered but also because there was no end to the list of remarkable people he’d known, produced, helped or counted as friends. But by then he’d given enough interviews in his life that he’d grown weary of them and I certainly didn’t want to pester him, in his own living room, with questions he’d been asked thousands of times before. Besides, it was just as fun to talk to him and Ann about other things, such the differences between national styles of aquavit (with samples!) or to hear stories about his hunting caribou in Alaska (for subsistence, not sport) or of the colorful artistic and literary types he and Ann knew in Sweden.

I had only known of Sam as a record producer and scholar of folk music and jazz. I soon learned that he was also a novelist, poet, translator, excellent classical pianist, jug,  washboard, banjo and clarinet player, Korean war veteran, art collector, jazz musician and literary scholar. And I’ve probably left some things out. He was also tireless.

washboard, banjo and clarinet player, Korean war veteran, art collector, jazz musician and literary scholar. And I’ve probably left some things out. He was also tireless.

Into his 70’s and 80’s he traveled extensively and seemed to never stop working or finding new additions to the Charters’ Archive. Crazy things would happen to him in his travels. On a trip to Scotland to visit his ancestral home town, he stopped to admire the sights and was approached by a local who recognized him. She was the co-owner of Document Records, a company that publishes meticulously documented collections of rare American music. She and her husband, the other co-owner, had been inspired by Sam and were great admirers. They invited Sam in to chat and the result was the UConn Archives receiving the huge full catalog of the Document label for inclusion in Sam and Ann’s collection.

It was a tremendous honor to know Sam Charters. I’ve never met anyone else like him and certainly never will again. His contribution to music, especially American music, is enormous and invaluable. And even though Sam is gone, his work and the music he loved, studied and recorded will be with us forever. One of the last things I wrote to Sam was that the Charters’ archive is in good, loving hands. I know someone who will see to that.

– Nicholas Eshelman

At 5:00pm (EST) today, tune in to WHUS Radio 91.7 FM to hear music produced and recorded by poet, novelist, and renowned scholar of the blues, jazz, and musical culture of the African diaspora Samuel Charters. Featuring our own Kristin Eshelman, Archivist for The Samuel and Ann Charters Archives of Blues and Vernacular African American Musical Culture at the University of Connecticut in Archives and Special Collections, the much-anticipated radio program is a tribute to the friendship, life and legacy of Samuel Charters. Samuel Charters died in March of this year at the age of 85.

At 5:00pm (EST) today, tune in to WHUS Radio 91.7 FM to hear music produced and recorded by poet, novelist, and renowned scholar of the blues, jazz, and musical culture of the African diaspora Samuel Charters. Featuring our own Kristin Eshelman, Archivist for The Samuel and Ann Charters Archives of Blues and Vernacular African American Musical Culture at the University of Connecticut in Archives and Special Collections, the much-anticipated radio program is a tribute to the friendship, life and legacy of Samuel Charters. Samuel Charters died in March of this year at the age of 85.

the same kind of thing but the record was interesting. John has never forgiven me for my note, and even if I’m not sure if we ever would really have become friends I have always been angry at myself for my insensitivity. John sent out a few copies of the record, which he had pressed for himself on his own Takoma label, and sold more through mail orders.

the same kind of thing but the record was interesting. John has never forgiven me for my note, and even if I’m not sure if we ever would really have become friends I have always been angry at myself for my insensitivity. John sent out a few copies of the record, which he had pressed for himself on his own Takoma label, and sold more through mail orders.

washboard, banjo and clarinet player, Korean war veteran, art collector, jazz musician and literary scholar. And I’ve probably left some things out. He was also tireless.

washboard, banjo and clarinet player, Korean war veteran, art collector, jazz musician and literary scholar. And I’ve probably left some things out. He was also tireless.