The UConn Archives & Special Collections podcast d’Archive will release it’s 50th episode on April 24th, 2023 with a live broadcast at 10am EST on 91.7fm WHUS. Beginning in August of 2017, the Archives staff began expanding its outreach program to the airwaves by training on sound engineering and radio protocols in order to effectively bring its collections to new audiences. Since then the radio program and podcast has featured weekly episodes drawing from countless collections held by the Archives & Special Collections and amplifying the expertise of over 60 collaborators ranging from past and present archives and library staff, artists, journalists, curators, faculty, graduate and undergraduate students, high school students, visiting fellows and international students, activists, alumni, collectors and donors, family, and friends.

Continue readingCategory Archives: Archives in Action

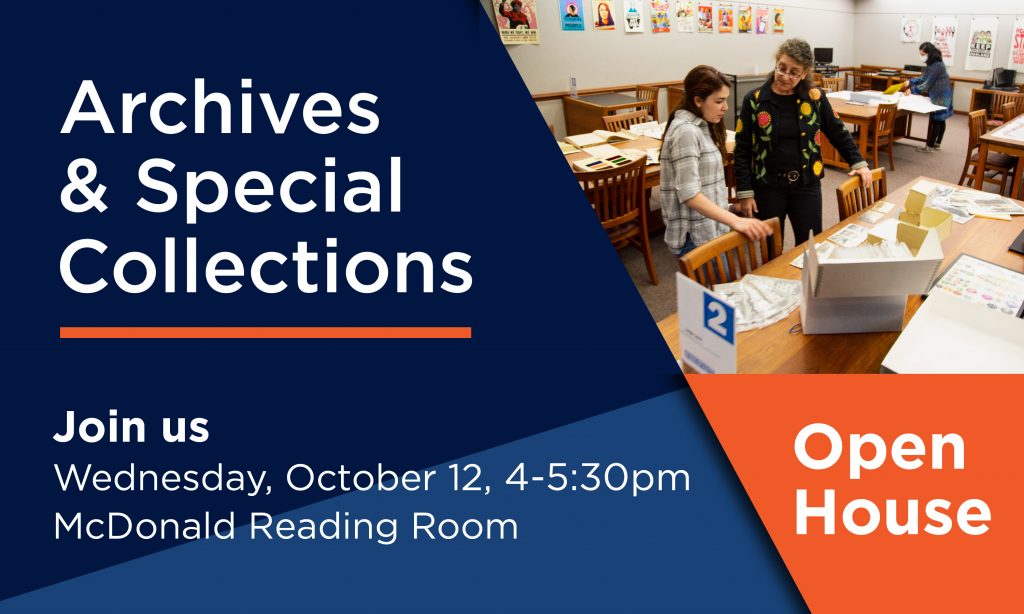

Celebrate American Archives Month with Archives & Special Collections at an Open House on October 12, 2022

Dodd Center for Human Rights from 4:00-5:30pm

Join us for a curated celebration of American Archives Month, behind-the-scenes tours, zine-making, giveaways, refreshments, and more!

Free and open to the public. All are welcome.

American Archives Month gives archives around the nation the opportunity to highlight the importance of records of enduring value. At UConn Archives we believe that archives reveal by enabling people to examine and better understand the past, that archives inspire by being useful for many purposes, and that archives are for everyone!

This is also the closing event for the exhibition Days and Nights of Prints and Punk in the Schimmelpfeng Gallery, providing your last chance to see the evolution of the punk rock scene over 4 decades.

October 12 is also #AskAnArchivist Day.

Archivists around the country will take to Twitter to answer your questions about any and all things archives. This day-long event, sponsored by the Society of American Archivists, will give you the opportunity to connect directly with archivists in your community—and around the country—to ask questions, get information, or just satisfy your curiosity. No question is too silly . . .

#AskAnArchivist Day is open to everyone—all you need is a Twitter account. To participate, just tweet a question and include the hashtag #AskAnArchivist in your tweet. Your question will be seen instantly by archivists around the country who are standing by to respond directly to you. Have a question for a specific archives or archivist? Include their Twitter handle with your question.

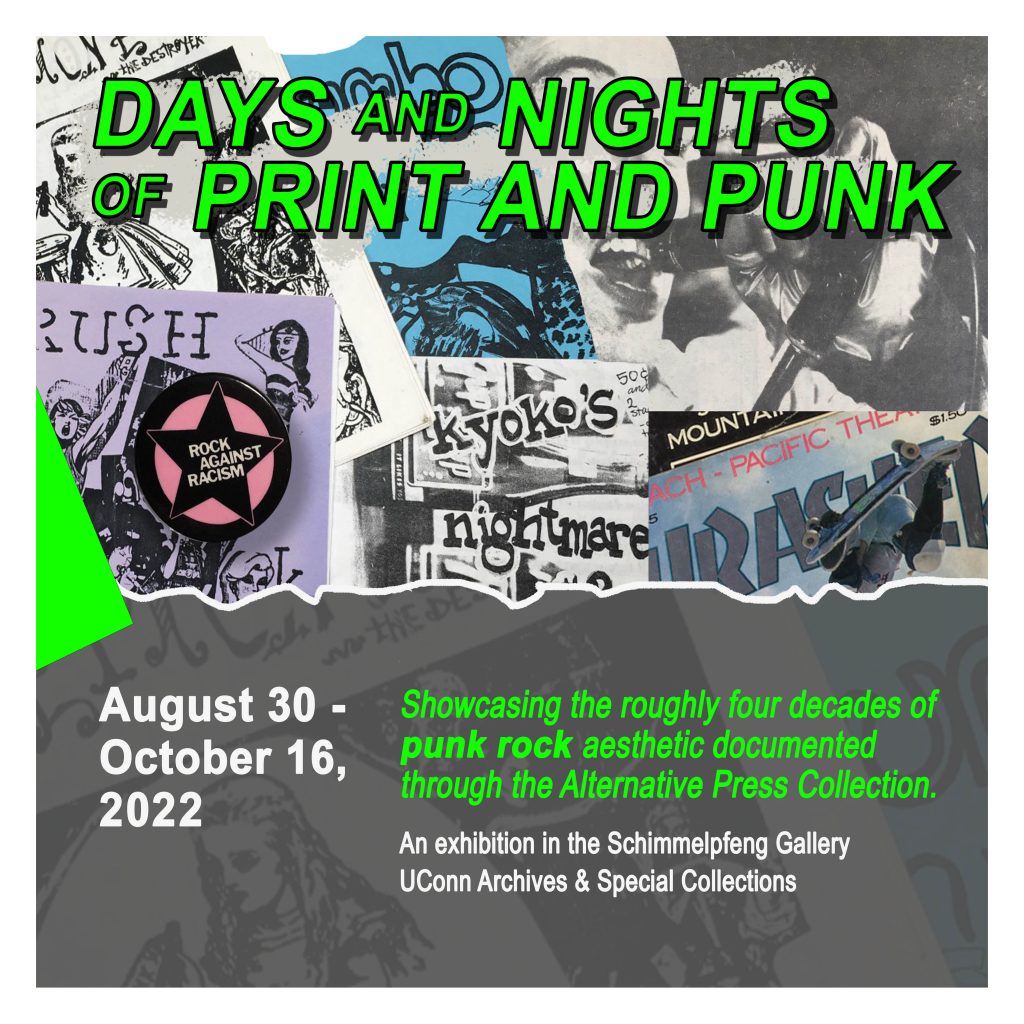

Days and Nights of Print and Punk

Exhibition on view August 30 – October 16, 2022

Monday through Friday, 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m

Schimmelpfeng Gallery, UConn Archives & Special Collections

Virtual Zine Workshop September 29, 12:30-1:30pm

Closing Event & Archives Open House October 12th, 4 – 6 pm.

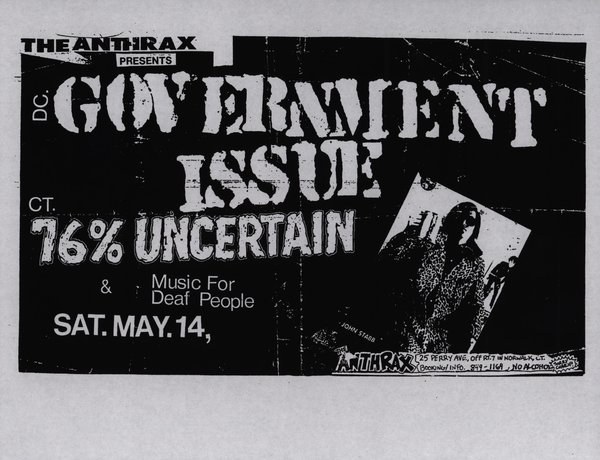

The UConn Archives & Special Collections presents Days and Nights of Print and Punk, showcasing the roughly four decades of punk rock aesthetic documented through the Alternative Press Collection. From the 1970s punk rock of bad attitudes and discontent in England and the U.S., seeds were sown to propagate a unified front of thumbed noses to the status quo. Those same attitudes of youth rebellion were reinterpreted from problems into solutions by each successive generation drawing from positive mental attitude, feminism, DIY socioeconomics, animal rights, and anti-racism. Through show flyers, riot grrrl and skate zines, t-shirts, stickers, vinyl, cassettes, and posters, the evolution of the scene has demonstrated its adaptability for youth movements from the late 1970s to the present day. This exhibition also features selections of performance photographs from the traveling exhibition Live at The Anthrax from the Joe Snow Punk Rock Collection. Joe photographed the thriving Connecticut Hardcore Punk (CTHC) scene in the late 1980s during the final years of The Anthrax club in Norwalk, CT (’86-’90). Shot on 35mm black and white Kodak film, these images represent historical documents that bring the viewer as close to the action as possible, providing an intimacy into this subcultural space from 35 years ago. The photographs were selected and reprinted with the intent to highlight the primacy of analog at that time as well as the aesthetics of the not-so-distant past illuminated by a sweat tinted flash bulb.

This exhibition is drawn from the following archival collections:

Andrews Punk Rock Collection, Fly Zine Collection, Kauffman Zine Collection, King Alternative Press Collection, Noelke-Olson Button Collection, and Snow Punk Rock Collection.

This exhibition is programmed in conjunction with the William Benton Museum of Art exhibition Wild Youth: Punk and New Wave from the 1970s and 1980s running concurrently.

D-I-Y Zine Basics September 29, 12:30-1:30pm via Zoom

Zines are DIY publications that have served as modes of expression as well as communication for underrepresented subcultures and social movements, including punk. They are analog and use a collage aesthetic to combine image and text in visually engaging ways. In this virtual workshop, learn about DIY publications with Archivist Graham Stinnett and Metadata Librarian Rhonda Kauffman to get started making your own zines. Held in conjunction with the exhibitions, Days and Nights of Print and Punk at UConn Archives’ Schimmelpfeng Gallery and Wild Youth: Punk and New Wave from the 1970s and 1980s at the William Benton Museum of Art.

Suggested materials list: • 1 sheet of letter sized paper • Magazines, newspapers, stickers to collage with, preferably images with high contrast. • Glue stick or tape • Sharpie fine and ultra fine permanent markers • 1-inch and ¾ inch alphabet stickers in various colors • Patterned Washi tape

Level Up materials list: • Label maker • Plastic bone folder • Alphabet stamps w/ink pad • Long arm stapler • Typewriter • Photocopier

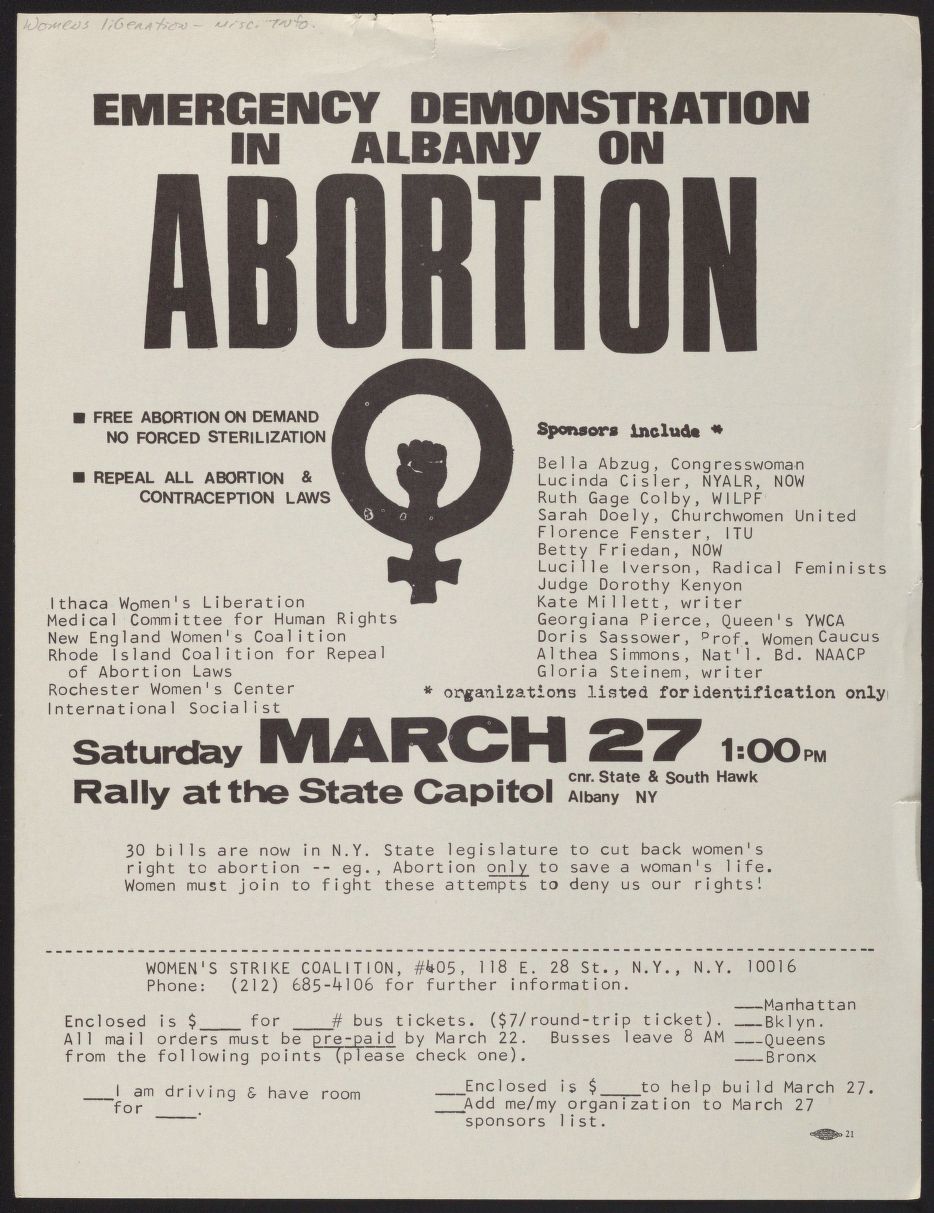

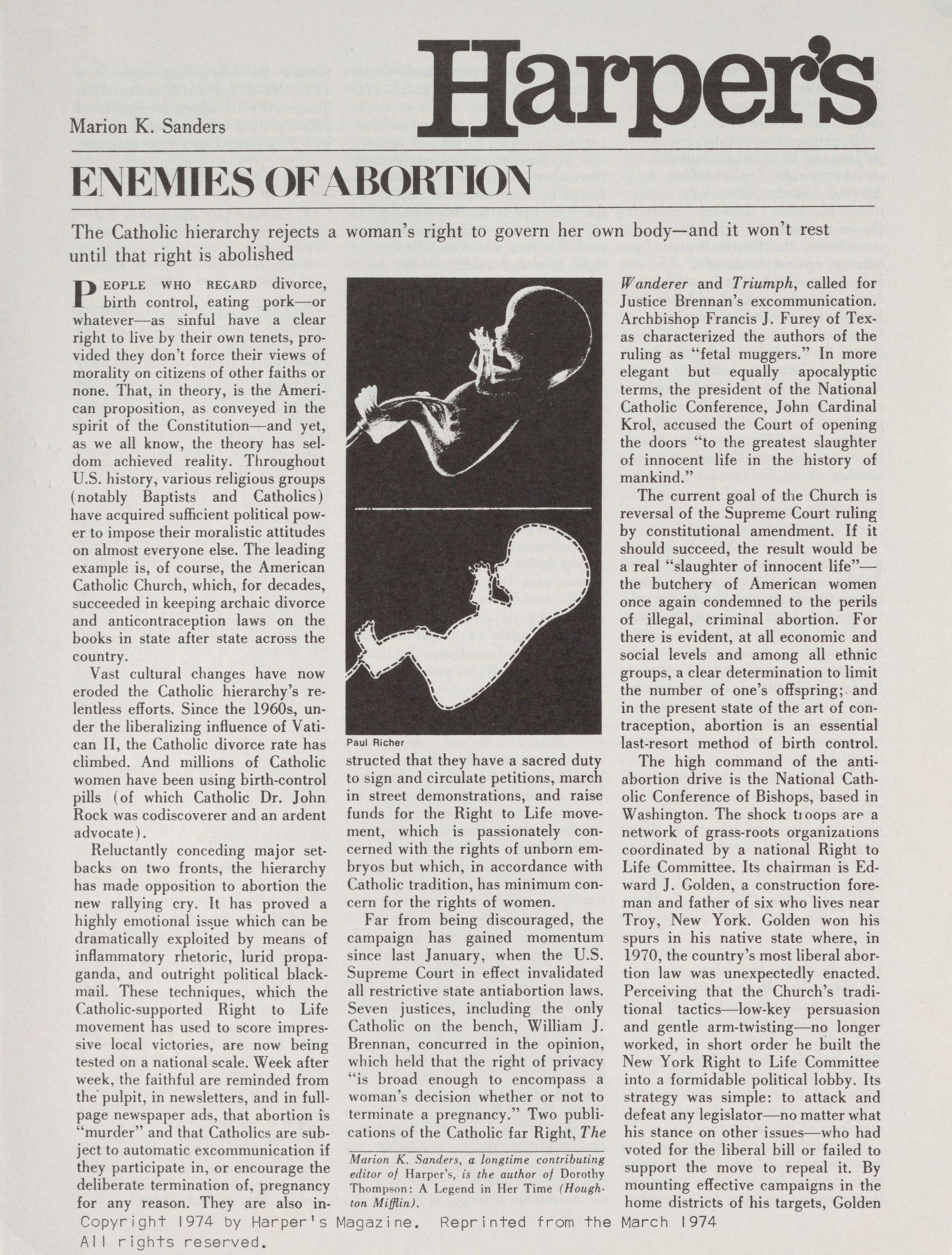

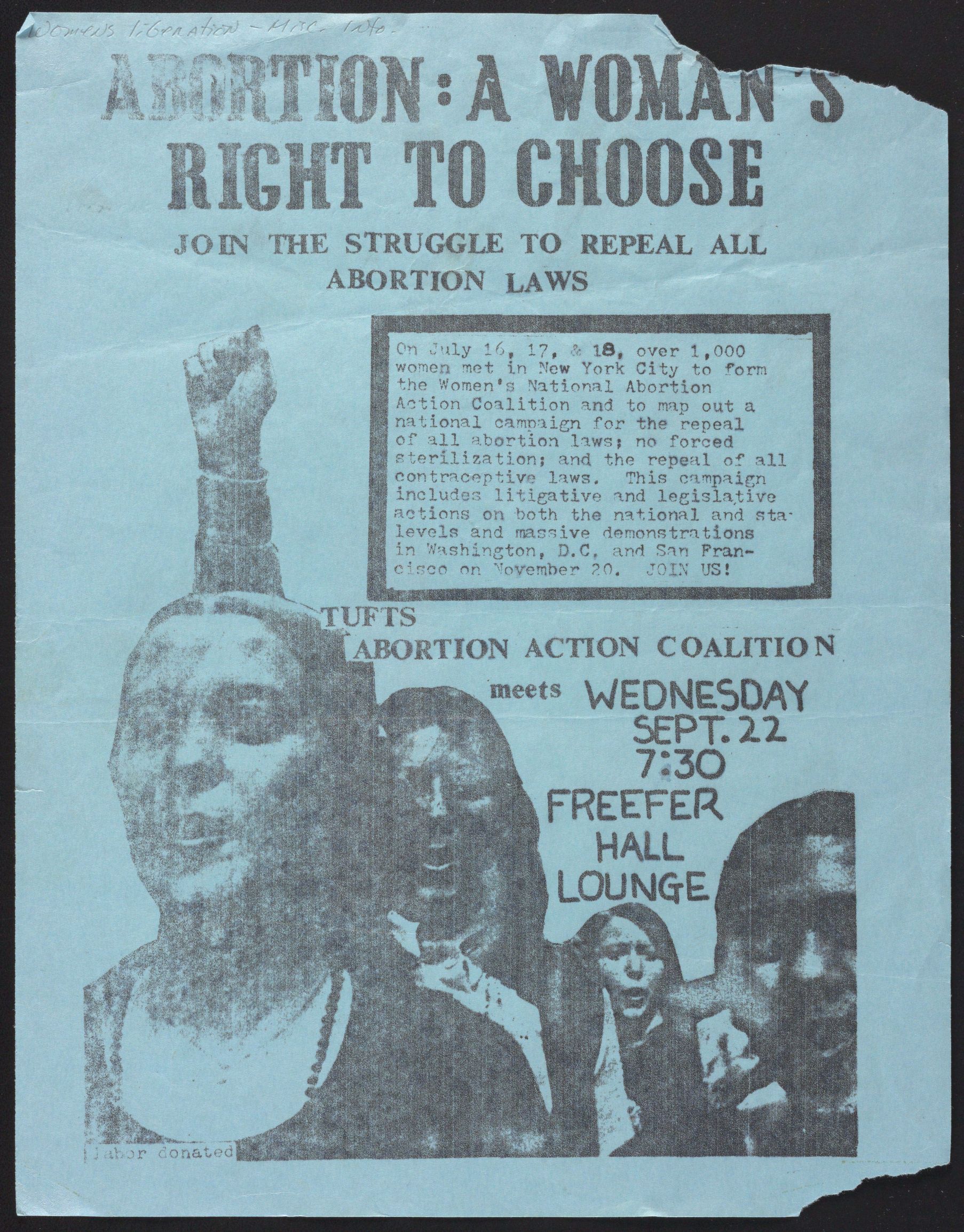

Resources in the Archives Related to Reproductive Rights and Abortion

In light of the June 24, 2022, United States Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overruled previous decisions Roe v. Wade (1973) and Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), Archives & Special Collections here provides a list of materials related to reproductive rights and abortion that are held in our collections.

The landmark decision in Roe in 1973 stated that “the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provides a fundamental “right to privacy” that protects a pregnant woman’s liberty to abort her fetus,” while the 1992 decision in Casey modified Roe by holding that requiring spousal awareness in order to get an abortion put undue burden on married people seeking abortions.

As of the 2022 decision in Dobbs, abortion is no longer a constitutionally guaranteed right in the United States, leaving the decision to individual states.

For those conducting research projects about reproductive rights, abortion, or related topics, Archives & Special Collections holds resources related to the topic in various media, both from pro-choice and anti-abortion perspectives. These materials range from polling information, correspondence, political documents, organizational literature, and much more. Among some of our archives’ relevant items are:

Connecticut Women’s Educational and Legal Fund Records. Connecticut Women’s Educational and Legal Fund (CWEALF) was founded in 1973. Related to reproductive rights, one major point in the collection is the Pregnancy Rights Project/Program, which took place in the 1980s, but CWEALF continues its work in advocacy, education, and empowerment to this day. Within the collection are publications, press releases from the organization, various writings, educational texts, administrative files, and more. Alongside reproductive advocacy, the records also include information on work CWEALF has done for LGBTQIA+ people. For more information on how to navigate this collection, a finding aid can be found online here: Connecticut Women’s Educational and Legal Fund Records

National Organization for Women, Connecticut and Rhode Island Chapters Records. Founded in 1966, the National Organization for Women is a feminist organization, with currently around 500,000 members. The organization advocates for women’s rights across many fronts, including reproductive health. This collection includes informational literature, meeting minutes, newspaper clippings, and more from both the Connecticut and Rhode Island chapters of NOW. For more information on how to navigate this collection, finding aids can be found online here: National Organization for Women, Connecticut Chapter Records and National Organization for Women, Rhode Island Chapter Records

Connecticut Civil Liberties Union Records. The CCLU was founded in 1949 as the New Haven Civil Liberties Council, and is now the Connecticut affiliate of the American Civil Liberties Union (it currently goes by the name ACLU of CT). This collection includes records from the original NHCLC, as well as administrative records from the CCLU from 1958-90. On the subject of reproductive rights, the collection includes legal documents from two cases: Women’s Health Services v. Maher (1979-1981) and Doe v. Maher (1981-90). Both deal specifically with Connecticut law surrounding abortion. For more information on how to navigate this collection, a finding aid can be found online here: Connecticut Civil Liberties Union Records

Alternative Press Collection Files. The Alternative Press Collection consists of publications created by various people, groups, and organizations. There are many items in the collection that cover the topics of reproductive rights and abortion, both in digitized online form and solely in the physical stacks. Below are a few links that will help to navigate the collection.

APC File Inventory – This link goes to a list of all the publications within the APC Files, both digitized and physical.

Connecticut Digital Archive – Various Publications Related to Abortion – This link goes to a digitized collection in the Connecticut Digital Archive titled “ABORTION.” It is made up of over 200 pages of literature.

Abortion Rights Movement of Women’s Liberation Advertisement – This link goes to an advertisement for ARM’s (Abortion Rights Movement) services to aid women in receiving, specifically late term abortions. Also includes a letter from Sandra Sullaway, Los Angeles coordinator of ARM (February 23, 1979).

Archives Batch Search for “APC Abortion” – This link goes to a search result on the UConn Library website that includes 22 results for items in the APC Files related to abortion.

Public Official’s Records. The following list are each their own collections, consisting of papers belonging to political officials, with each collection including text related to reproductive rights or abortion. For more information on how to navigate these collections, finding aids can be found online at the links with each name.

Audrey Beck Papers – Audrey P. Beck (1931-1983) was a Connecticut politician and professor. She served in the Connecticut House of Representatives from 1967 to 1975, followed by a term in the Connecticut Senate from 1975 until her death in 1983. Prior to her political career, Beck taught Economics at the University of Connecticut.

Barbara B. Kennelly Papers – Barbara B. Kennelly (born 1936) is a former U.S. Representative from Connecticut’s 1st District, where she served from 1982 to 1999. Prior to this, she served as Connecticut Secretary of State from 1979 until 1982.

Chase Going Woodhouse Papers – Chase G. Woodhouse (1890-1984) was a U.S. Representative from Connecticut’s 2nd District, where she served two terms, from 1945 to 1947 and then from 1949 to 1951. Prior to this, she served as Secretary of State of Connecticut from 1941 to 1943.

Nancy L. Johnson Papers – Nancy L. Johnson (born 1935) is a former U.S. Representative, where she served both Connecticut’s 6th District from 1983 to 2003 and its 5th District from 2003 to 2007. From 1995 to 1997, she chaired the House Ethics Committee. She served in the Connecticut Senate from 1977 to 1983.

Prescott S. Bush Papers – Prescott S. Bush (1895-1972) was a U.S. Senator from Connecticut, serving from 1952 to 1963.

Robert N. Giaimo Papers – Robert N. Giaimo (1919-2006) was a U.S. Representative from Connecticut’s 3rd District, where he served from 1959 to 1981.

Robert R. Simmons Papers – Robert R. Simmons (1943-) is a former U.S. Representative from Connecticut’s 2nd District, serving from 2001 to 2007. He served in the Connecticut House from 1991 to 2001, and after he left office he served as First Selectman of Stonington, Connecticut from 2015 until 2019.

Sam Gejdenson Papers – Sam Gejdenson (1948-) is a former U.S. Representative from Connecticut’s 2nd District, where he served from 1981 to 2001. He served in the Connecticut House of Representatives from 1975 to 1979.

Stewart B. McKinney Papers – Stewart B. McKinney (1931-1987) was a U.S. Representative from Connecticut’s 4th District, where he served from 1971 until his death in 1987. He served in the Connecticut House of Representatives from 1967 to 1971.

William R. Cotter Papers – William R. Cotter (1926-1981) was a U.S. Representative from Connecticut’s 1st District, where he served from 1971 until his death in 1981.

Connecticut State Labor Council, AFL-CIO Records. This collection consists of the records of the Connecticut branch of the AFL-CIO, the United States’ largest labor union federation. Relating to the issues of reproductive rights and abortion, one item that the collection has is a group of letters from people commenting on whether or not the union should take a pro-choice stance. This debate took place in the early 1990s, and since then, the AFL-CIO currently is a pro-choice organization. For more information on how to navigate this collection, a finding aid can be found online here: Connecticut State Labor Council, AFL-CIO Records

American Association of University Women, Connecticut Division Records. Founded in the 1880s by Marion Talbot, a graduate of Boston University, and Ellen Swallow Richards, an MIT graduate, what began as the Association of Collegiate Alumnae has been supporting women who have graduated from college ever since. This collection includes information on the organization’s history, programs it has run, legal activity, information on specific branches within Connecticut, and more. Information on what the AAUW has done regarding reproductive rights can be found mostly in the legislative information section. For more information on how to navigate this collection, a finding aid can be found online here: American Association of University Women, Connecticut Division Records

Laurie S. Wiseberg and Harry Scoble Human Rights Internet Collection. The Human Rights Internet consists of materials related to human rights organizations from across the world, including newspapers, reports, NGO literature, books, journals, correspondence, and more. The collection began in 1977, with Drs. Laurie Wiseberg and Harry Scobie as its founders. It includes human rights documents in many languages, including “English, French, Spanish, Dutch, German, Swedish, Chinese and Japanese (among many others),” according to the finding aid. Within the collection are materials belonging to Human Rights Watch, the International Council on Human Rights Policy, Amnesty International, and Anti-Slavery International. For more information on how to navigate this collection, a finding aid can be found online here: Laurie S. Wiseberg and Harry Scoble Human Rights Internet Collection

Connecticut Citizens Action Group Records. Founded in the early 1970s by Ralph Nader and Toby Moffett, CCAG states that its goal is to empower citizens of Connecticut in their roles as “consumers, workers, tax payers, and voters.” Information on reproductive rights may be found within the “Health Project” series of the collection, as well as in Director Marc Caplan’s files. For more information on how to navigate this collection, a finding aid can be found online here: Connecticut Citizens Action Group Records

Samuel Lubell Papers. Samuel Lubell (1911-1987) a journalist and public opinion pollster. This collection includes notes, manuscripts, correspondence, and reports belonging to Lubell. One portion of this collection that is relevant to reproductive rights is public opinion polling he did of students in the 1960s, with abortion being one of the topics polled about. More broadly, he also worked on studies related to women’s issues in the 1940s and 1950s. For more information on how to navigate this collection, a finding aid can be found online here: Samuel Lubell Papers

Stephen Thornton Papers. Stephen Thornton (born 1951) is a community organizer in Connecticut. Since his days at UConn organizing student protests of the Vietnam War, Thornton has been advocating for various causes, with groups such as the Peoples Bicentennial Commission, the Anti-Racist Coalition of Connecticut, and more. This collection includes newspapers, alternative press, flyers, correspondence, notes, writings, and other forms of paraphernalia. Within the collection are some items related to reproductive rights. For more information on how to navigate this collection, a finding aid can be found online here: Stephen Thornton Papers

This post was written by Sam Zelin, formerly a UConn undergraduate student in the Neag School of Education who was a student assistant in Archives & Special Collections.

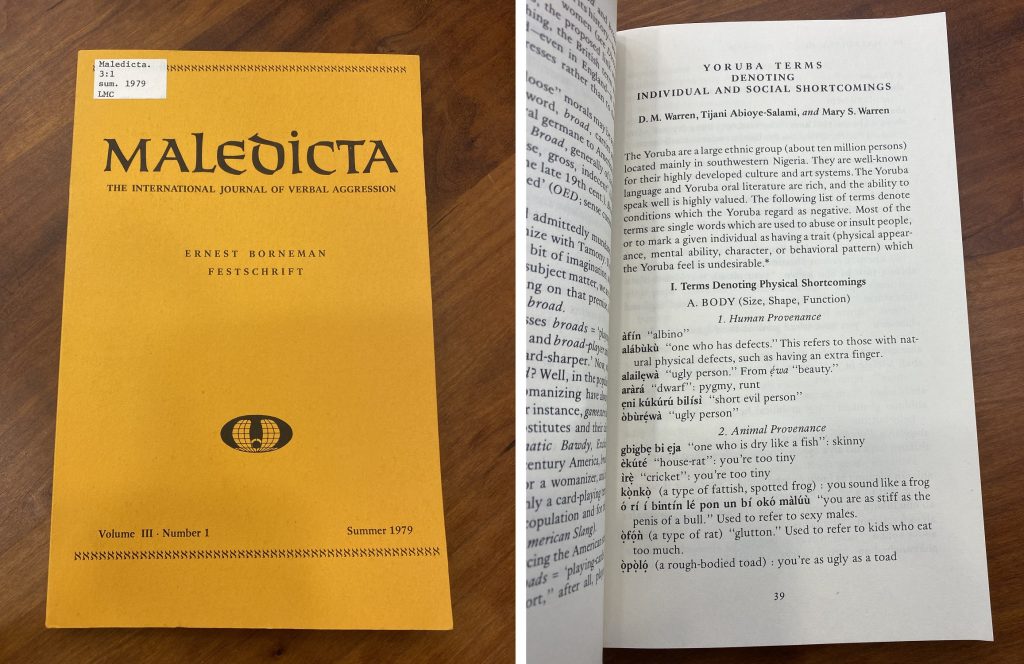

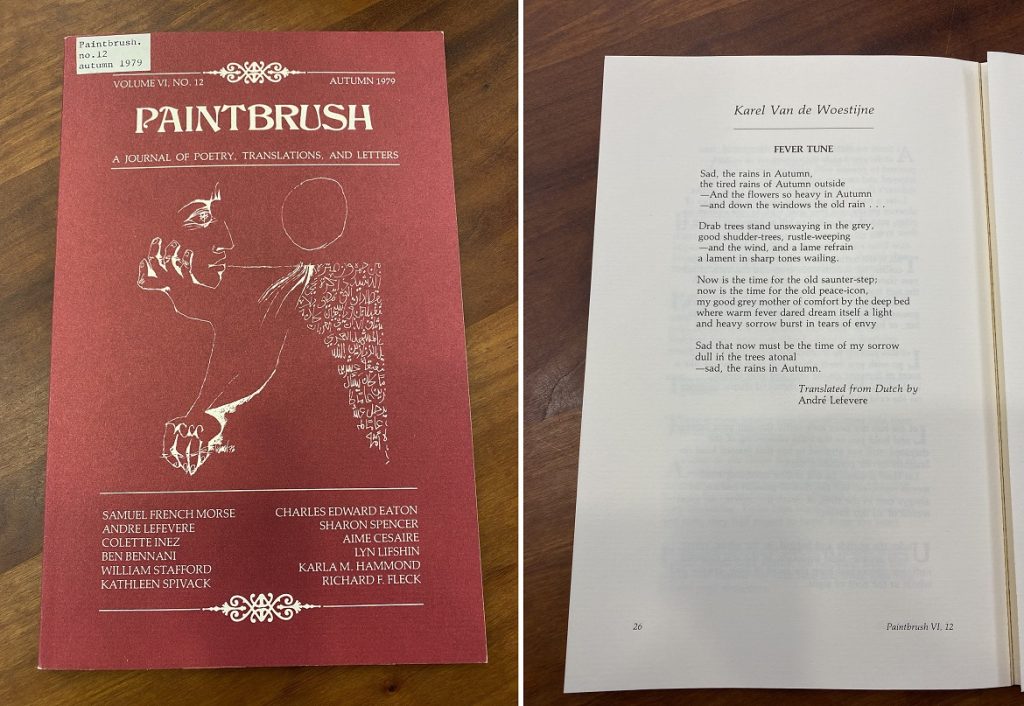

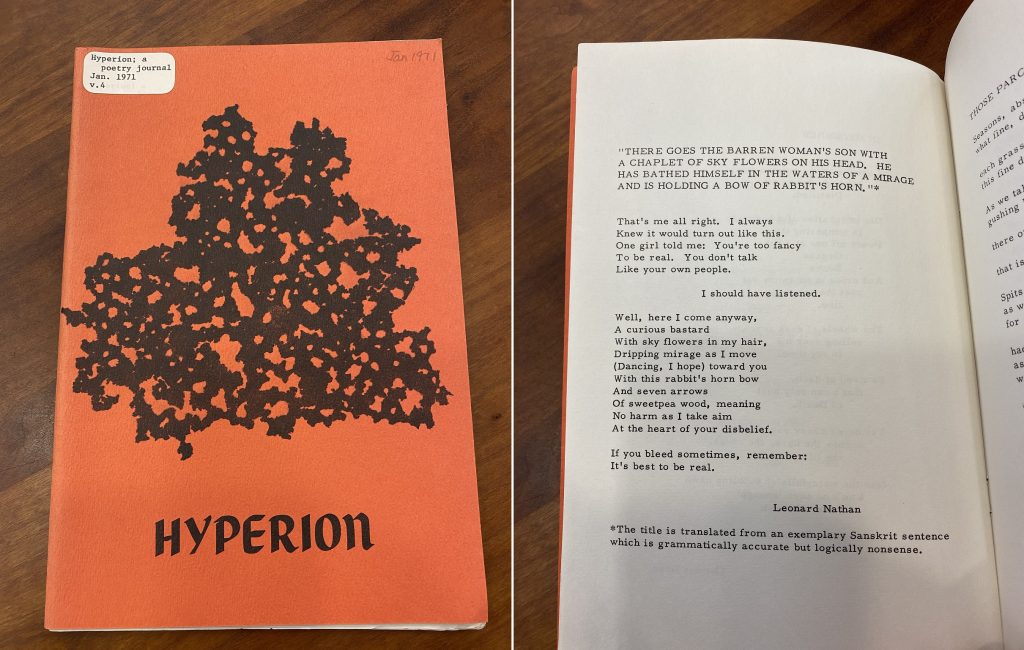

Poetry in Translation in the Little Magazines Collection

A project by Nicole Catarino, UConn English Department Writing Intern, Spring 2022. Background by Melissa Watterworth Batt, Archivist

Project Background

Literary periodicals of the 1900s exerted a strong influence on the poetics and shifting literary trends of the twentieth century. Many of these periodicals were edited by writers themselves and deliberately circulated outside, or on the margins, of popular media.

With the introduction of the personal computer and new offset printing technology in the 1970s, independent presses, often short-lived and with small budgets, thrived. Non-profit publishing organizations of the period assisted with distribution, providing grants to establish presses and distribution networks internationally.

Ironically, small print runs, while less profitable, enabled independent presses to stay afloat during the economic turmoil of the 1980s when many corporate, commercial publishing companies cancelled or suspended operations in the literary marketplace. By the mid-1980s, a diversifying publishing industry offered new writers, including non-English language writers, expanded opportunities for publication.

Bibliography

My name is Nicole Catarino, an English major and literary translations minor here at the University of Connecticut, graduating with the Class of 2022, and for the length of the Spring 2022 semester, I have been an intern at UConn’s Archives and Special Collections Department working with Archivist Melissa Watterworth Batt. My internship project revolved around the Archive’s collection of little magazines and the published translations one can find in these literary journals.

“Little magazines” are defined as periodicals produced with small budgets and a limited team, and experienced small print runs and limited distribution. These publications were often short-lived. Today, the Little Magazine collection here at UConn is comprised of over 700 titles from the 1920s to the 2000s, representing a wide array of writers and writing styles, experimental works, graphic novels, zines, and artists books.

However, despite the Little Magazine Collection’s diverse grouping of literary journals and other periodicals, Archivist Watterworth Batt and I realized that very little research had been conducted for the genre of literary translations. That’s when we arrived at the initial idea for my internship project. My goal was to create a cohesive bibliography of little magazines in the collection that published translated works in their journals.

We decided to set our focus on the little magazines that were founded or running in the 1980s because that was the era in which publication started to become cheaper and more accessible. As a result, independent writers and editors began to create journals that stepped away from the themes and content of mainstream publications and instead focused on experimental styles, forms, and genres while also providing a space for new and emerging writers. Archivist Watterworth Batt and I agreed that if there was ever a time for translations to become more popular in the world of little magazines, it would be the 1980’s.

Ultimately, the reason why I chose to focus on literary translations, of all genres, was for two purposes. One was because as a student minoring in literary translations, I knew that a detailed bibliography about where to find translation-focused literary journals would be a fantastic resource for both students and professors alike. My second reason, however, stemmed from my own love for translations and my frustration that this genre of literature is frequently not given the same credit and valor as other literary genres. Translations are complicated and elegant facets of literature that allow us to share cultural stories, folklore, and perspectives on the human experience that otherwise would go unnoticed or unheard due to the language barrier. For this reason, I wanted to highlight these kinds of creative works and find how many resources there are for this genre of literature here at UConn.

The bibliography I created for this project contains six main categories in the spreadsheet: the title of the little magazine that published the translation, the original language the piece was written in, the writer who wrote the original piece, the translator who wrote the translation, the volume and number of the corresponding issue and when it was published, and then any other interesting writers of note or extra information about the journal that I may have discovered. The purpose of this last section was to emphasize just how important little magazines are for writers by listing many famous authors and poets who got their start by publishing in little magazines—like Margaret Atwood, Joyce Carol Oates, and Adrienne Rich, among others.

My hope is that, aside from providing a useful resource to translators and researchers, this bibliography will help stir more interest in the Archives’ magnificent collection of little magazines, so if you have the chance to browse the collection, I highly encourage you to do so!

Strengthening UConn’s Presence on Wikipedia

The post was contributed by Michael Rodriguez, Collections Strategist at the UConn Library.

The University of Connecticut has a strong presence on Wikipedia, which goes under the tagline “the free encyclopedia that anyone can edit.” In a personal summer project, I wrote thirty new encyclopedia articles and expanded seven others about influential figures in UConn’s history. For sources, I drew on texts and images from Archives and Special Collections, as well as other UConn Library resources that brought to life the university’s remarkable history and people.

Background

Wikipedia is one of the world’s most-viewed websites. Founded in 2001, Wikipedia has over 6 million articles and 3.5 billion words in English alone. Edits happen at a rate of 1.9 per second. Wikipedia is the first stop for millions of people seeking a quick fact, a topic overview, or links to other sources. But because Wikipedia is 100% crowdsourced, articles exist only if someone cares enough to write them and then navigate Wikipedia’s maze of rules to publish them.

When I began editing, eleven of UConn’s twenty-one presidents and principals lacked Wikipedia articles about them. Notable scholars such as Henry P. Armsby and Nathan L. Whetten had zero representation. Wikipedia had little coverage of influential faculty and philanthropists whose names we see on campus buildings. Not a single woman who had a campus building named after her was represented on Wikipedia, reflecting Wikipedia’s longstanding gender gap.

Wikipedia cautions against editing where editors may have a conflict of interest. I wrote my contributions off the clock, but even so, I generally avoided writing about living people. I wrote about no one I knew. I consulted a range of sources, citing not only university publications, for instance, but also the Hartford Courant and other sources unaffiliated with UConn.

Who did I write about?

First, I wrote about UConn women with buildings named in their honor. Did you know that Josephine Dolan—the first nursing professor at UConn—built the school’s Dolan Collection of Nursing History? Did you know that the namesake of the M. Estella Sprague Residence Hall served as UConn’s first dean of home economics in the 1920s? Did you know that the Frances Osborne Kellogg Dairy Center is named for one of Connecticut’s earliest female business executives? Her home is a state museum on the Connecticut Women’s Heritage Trail.

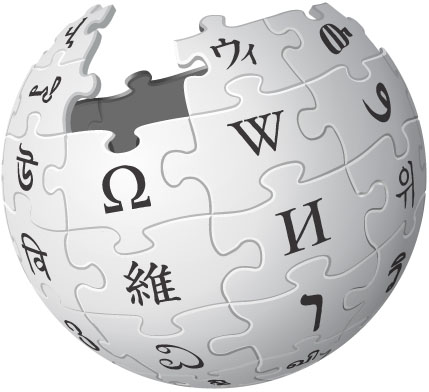

Second, I wrote about UConn presidents. Did you know that the college’s first leader, Solomon Mead, patented a special plough? Or that Harry J. Hartley was named Man of the Year by the Daily Campus student newspaper in 1978? Or that Charles L. Beach commissioned Ellen Emmet Rand to paint a posthumous portrait of his beloved wife, Louise? Or that Benjamin F. Koons fought in 17 Civil War battles and ran an Alabama freedman’s school during Reconstruction?

Third, I wrote about the chroniclers of UConn’s history. Did you know that Jerauld Manter, who served as UConn’s unofficial photographer for half a century, has a gnat named after him? Or that forty-eight erstwhile Daily Campus student editors attended the retirement party of their mentor Walter Stemmons, chronicler of UConn’s first semicentennial? Or that Bruce M. Stave, who literally wrote the book on UConn, was president of the Federation of University Teachers during the campaign that brought collective bargaining to the university in 1976? Stemmons and Stave wrote authoritative histories, including Connecticut Agricultural History: A History (1931) and Red Brick in the Land of Steady Habits (2006). These chroniclers were such key sources for so many articles that I had to celebrate them with articles of their own.

Fourth, I wrote about influential faculty. Sidney Waxman brought along his .22 rifle on car trips, shooting down pinecones to augment his dwarf conifer collection. Henry Ruthven Monteith’s daughter, Marjorie, scored the second goal at UConn’s first women’s basketball game. George Safford Torrey played the organ and carillon at Storrs Congregational Church. Albert E. Waugh, provost for decades, was the only American member of a German group called Friends of Old Clocks. While I necessarily focused on getting facts right, the humanity of these figures, as well as their remarkable contributions to science and to the school, shone through my sources.

Finally, I wrote about figures who, while not faculty members or presidents, nevertheless exerted a powerful influence on the university’s history. Charles and Augustus Storrs donated land and money to start the university in 1881. T. S. Gold was godfather of the school from its inception, shepherding it through its infancy and ensuring it remained viable and appropriately resourced. The Ratcliffe Hicks School of Agriculture was named for an industrialist up the road in Tolland. Ratcliffe’s daughter, Elizabeth Hicks, has a UConn residence hall named in her honor.

Using the archives

UConn Library’s Archives & Special Collections (ASC) were an incredible resource. ASC collects the papers of presidents, prominent faculty, and other figures associated with the University. To inventory materials and guide researchers, archivists write finding aids, which often include biographical information. Finding aids proved a valuable source, as well as helping me assess who was notable enough to merit Wikipedia articles about them. I linked to finding aids in the “External links” section of most of my Wikipedia contributions, ensuring bibliographical depth.

For each article I wrote, I searched the Connecticut Digital Archive (CTDA), a UConn-sponsored statewide repository for digital cultural heritage materials. I searched the CTDA for digital scans of old photographs, newspapers, Nutmeg yearbooks, and booklets such as Three Pioneers and Handbook of Connecticut Agriculture. I combed past issues of UConn Today and its forerunner, UConn Advance, looking for commemorative essays. Mark J. Roy’s charming series A Piece of UConn History, which ran from 1997 to 2005, was especially useful. In addition, I drew on posts by archivists and graduate students on UConn’s Archives & Special Collections Blog.

Finally, I drew on the expertise of archivists. I requested high-resolution images from University Archivist Betsy Pittman when scanned online copies proved too pixelated for Wikipedia. Betsy even found me a never-before-digitized photo of UConn coach and acting president Edwin O. Smith. I am grateful for both archives and archivists—the collective memory of the university.

In addition to contributing text, I contributed images to Wikimedia Commons and Wikipedia. I took photos of various named campus buildings—and a European larch dwarf conifer cultivated by Sidney Waxman—and released the images for unlimited public use on Wikimedia Commons. I downloaded pre-1925 portrait photographs from the CTDA and uploaded them to Wikimedia Commons too, maximizing their discoverability and linking back to the CTDA. Where no portrait existed online, I tracked down group photos in yearbooks or newspapers, took screen captures, and cropped them. When the only extant photos were not clearly uncopyrighted, I used one of the very few fair use exceptions permitted by Wikipedia, in which historic portraits of deceased persons may be uploaded solely to illustrate their Wikipedia biography. I sourced most images from UConn’s archival collections, as well as from UConn Today and various books and serials in HathiTrust Digital Library. Contributing images to Wikipedia is a great way to boost visibility of those images while driving traffic to UConn’s digital archival content in the CTDA.

What’s next?

UConn’s people, places, and unique resources are better represented on Wikipedia than ever. But this work is hardly done. I plan to monitor the in-memoriam section of UConn Today—what better way of acknowledging a prominent professor’s passing than ensuring that they get the most widely read Who’s Who-equivalent entry on the planet? In fact, one of my most recent articles was on Roger Buckley, founding director of the Asian and American Studies Institute, who died in August 2020. I will continue to create articles for UConn people with landmarks named in their honor, such as puppeteer Frank W. Ballard and cellist J. Louis von der Mehden.

On Wikipedia, the editing never ends.

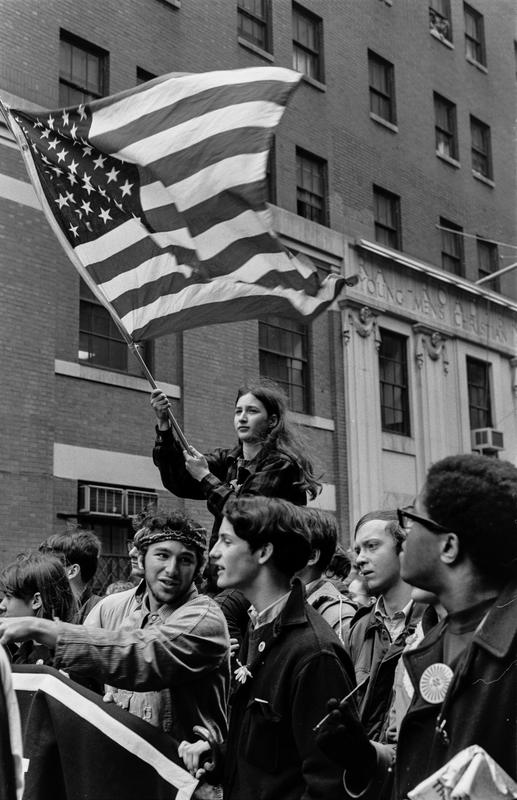

Student Unrest Photography in 4D

New York Peace March, April 15, 1967

In the Spring semester of 2020, an exciting use of historical photographs by UConn Digital Media and Design students brought to life the images of student protest in the 1960s and 1970s held by the University of Connecticut Archives. In collaboration with Assistant Professor Anna Lindemann and MFA graduate Instructor Jasmine Rajavadee of the Digital Media and Design Department, the Motion Graphics 1 class (DMD 2200) spent a portion of their semester in the archives to understand the context of photographic collections and practice their skills on digital collection items. This exploration led to the creation of new uses for the recorded past. The class assignment drew on digitized 35mm negatives, Kodachrome color slides, and black&white photographic prints to demonstrate a 4D animation process of still images to bring static subjects to life. Collections utilized for this project ranged from the Cal Robertson Collection of anti-nuclear demonstrations in New London, Howard S. Goldbaum’s Photography for the Daily Campus newspaper documenting anti-Vietnam War demonstrations in Storrs, New York, and Washington D.C., and University of Connecticut Photography Collection images of the 1974 Black Student sit-in at Wilbur Cross Library. To view a selection of the Student Unrest Photography in 4D project, follow this link to our Youtube page.

This project was a timely and innovative use of a subject matter that was re-energized through Storrs campus demonstrations around racism, global climate change and mental health advocacy throughout the 2019-2020 academic year. In addition, UConn Archives exhibitions Day-Glo & Napalm: UConn from 1967-1971 on student life and activism of the Vietnam War Era and UConn Through the Viewfinder: Connecticut Daily Campus Photographs from the Howard Goldbaum Collection at the William Benton Museum of Art reminded the community of it’s involvement during times of national change.

This is the second time that the UConn Archives has worked with Prof. Lindemann and the DMD department to utilize photographic collections for class projects, the first drew on child labor images from the U. Roberto Romano Collection which can be viewed here.

Musicology in the Archives

The Spring 2020 semester is off to a roaring start with curricular engagement in the Archives & Special Collections. In addition to several classes visiting the archives for introductory sessions, return visits for collections use, and weekly sessions about memory and the recorded past, the UConn archives is taking part in teaching a School of Music seminar for the first time this semester. Currently, Archivist Graham Stinnett is co-teaching Music 3410W on Archives, Music, Memory and Culture with Prof. Jesús Ramos-Kittrell, Assistant Professor in Residence of Music History and Ethnomusicology in the UConn School of Fine Arts.

Students have engaged with assigned readings from popular culture scholars to critical theorists, amateur historians and archivists, as well as producers in the record business and public librarians. The course works with three major musical genres, the Country Blues, Psychedelic Rock, and Punk Rock drawing from the respective collecting areas at the UConn Archives: Samuel and Ann Charters Archives of Blues and African American Vernacular Musical Culture; Alternative Press Collection; Joe Snow Punk Rock Collection. Students are asked to engage with primary sources to investigate the production of a musical culture through its recorded past. As a writing class requirement the students will produce a research project and presentation drawing on topics found in the archives as well as their personal experiences with music in the digital age and notions of their own personal archives as far as the materialist commodity of music is concerned.

We look forward to working with students this semester to develop their critical learning skills through archives and producing unique and engaging projects that shed light on how young adults engage with music and make it their own.

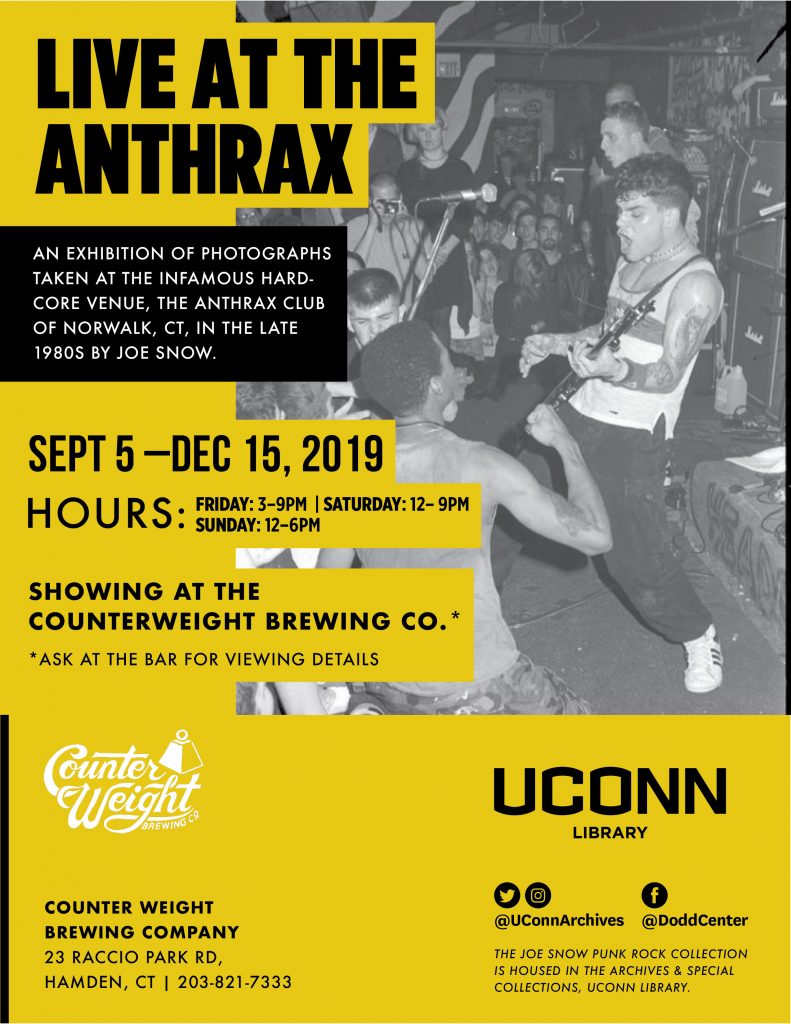

UConn Archives Punk Photography at Counter Weight Brewing Co.

The next installation of the traveling exhibition, Live at The Anthrax, is currently hosted at Counter Weight Brewing Co. in Hamden, CT and will run from September 5th-December 15th, 2019. This exhibition features 20 black & white photographs from the Joe Snow Punk Rock Collection, taken by Joe in the late 1980s during the final years of The Anthrax club in Norwalk, CT. Bands featured in the selection include local CTHC staples such as Wide Awake and NY Hardcore bands Up Front and Absolution to seminal acts such as Fugazi. This curated exhibition highlights the dedication, energy and lived values of those who formed the hardcore scene and turned it into a community. This exhibit seeks to expose the public to archival collections outside of a traditional archives setting in order to promote access to rich cultural materials like those of the Joe Snow Punk Rock Collection in everyday spaces like record stores, breweries and community spaces. This exhibition is free and open to the public.

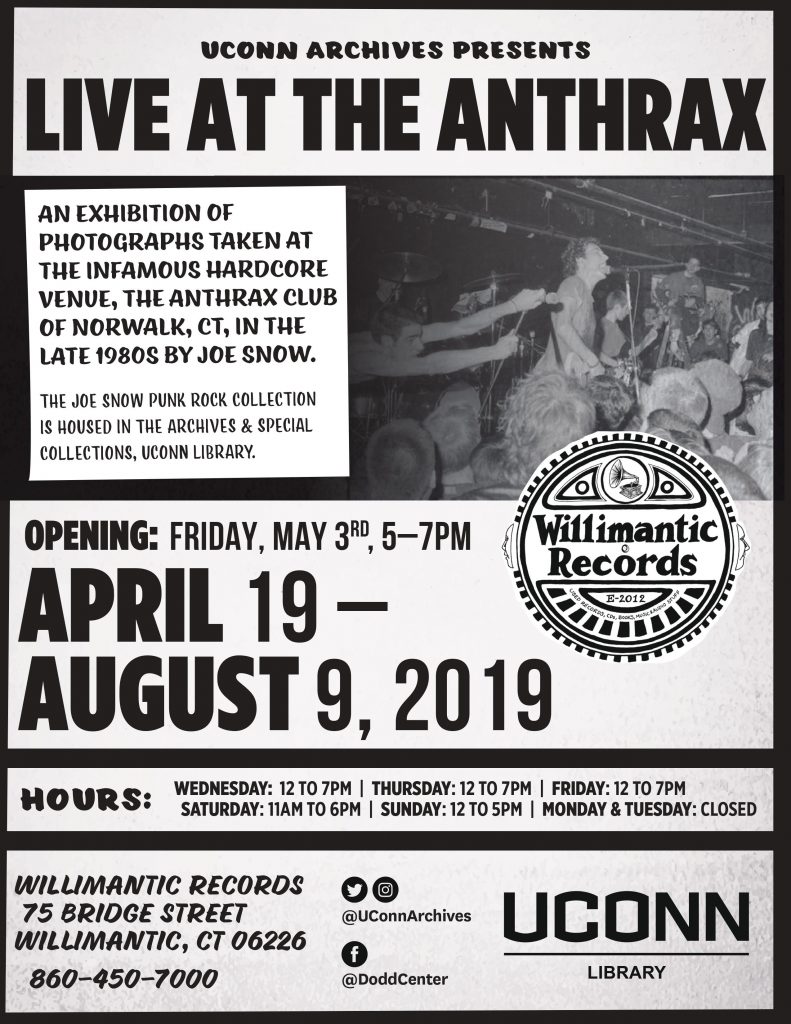

Punk Rock Photography Exhibition: Live at the Anthrax

The UConn Archives presents Live at the Anthrax, an exhibition of performance photography from the Joe Snow Punk Rock Collection, on display for the first time. Joe photographed the thriving Connecticut Hardcore Punk Rock (CTHC) scene in the late 1980s during the final years of the Anthrax club in Norwalk. Bands featured in the selection include local CTHC staples such as Wide Awake and NY Hardcore bands Up Front and Absolution to seminal acts such as Fugazi. This curated exhibition highlights the dedication, energy and lived values of those who formed the hardcore scene and turned it into a community. On display at Willimantic Records from April 19 – August 9, 2019 with a featured opening event on May 3rd from 5-7pm. This event is free and open to the public.

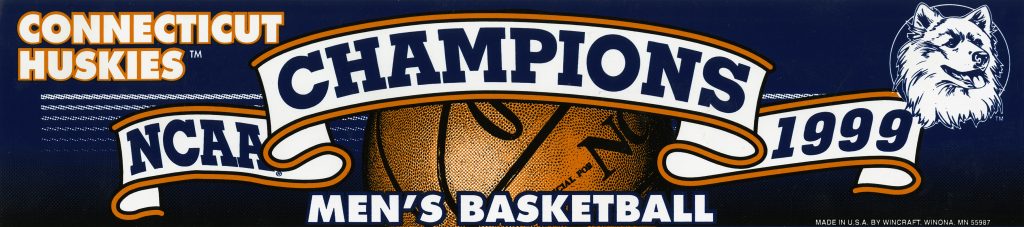

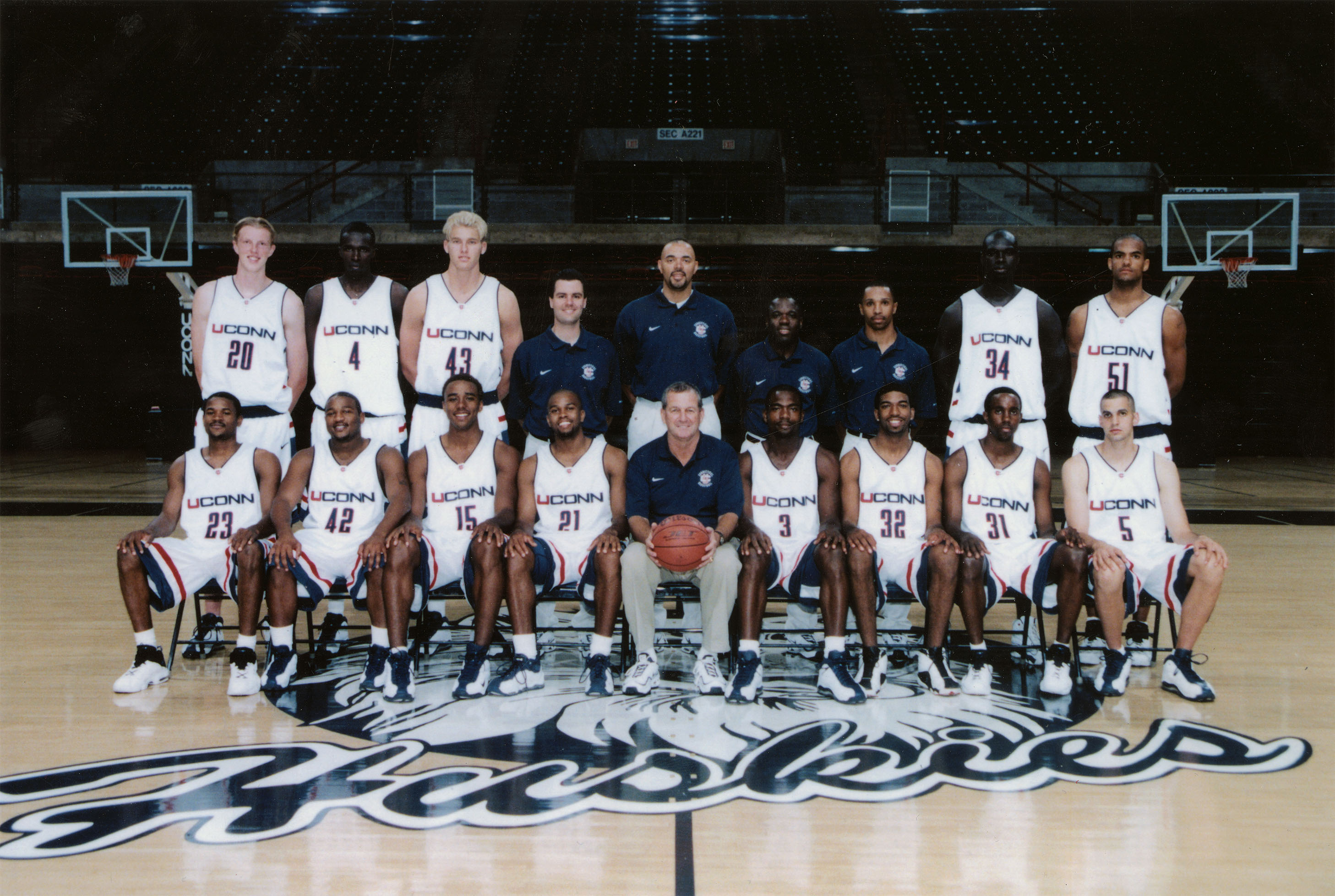

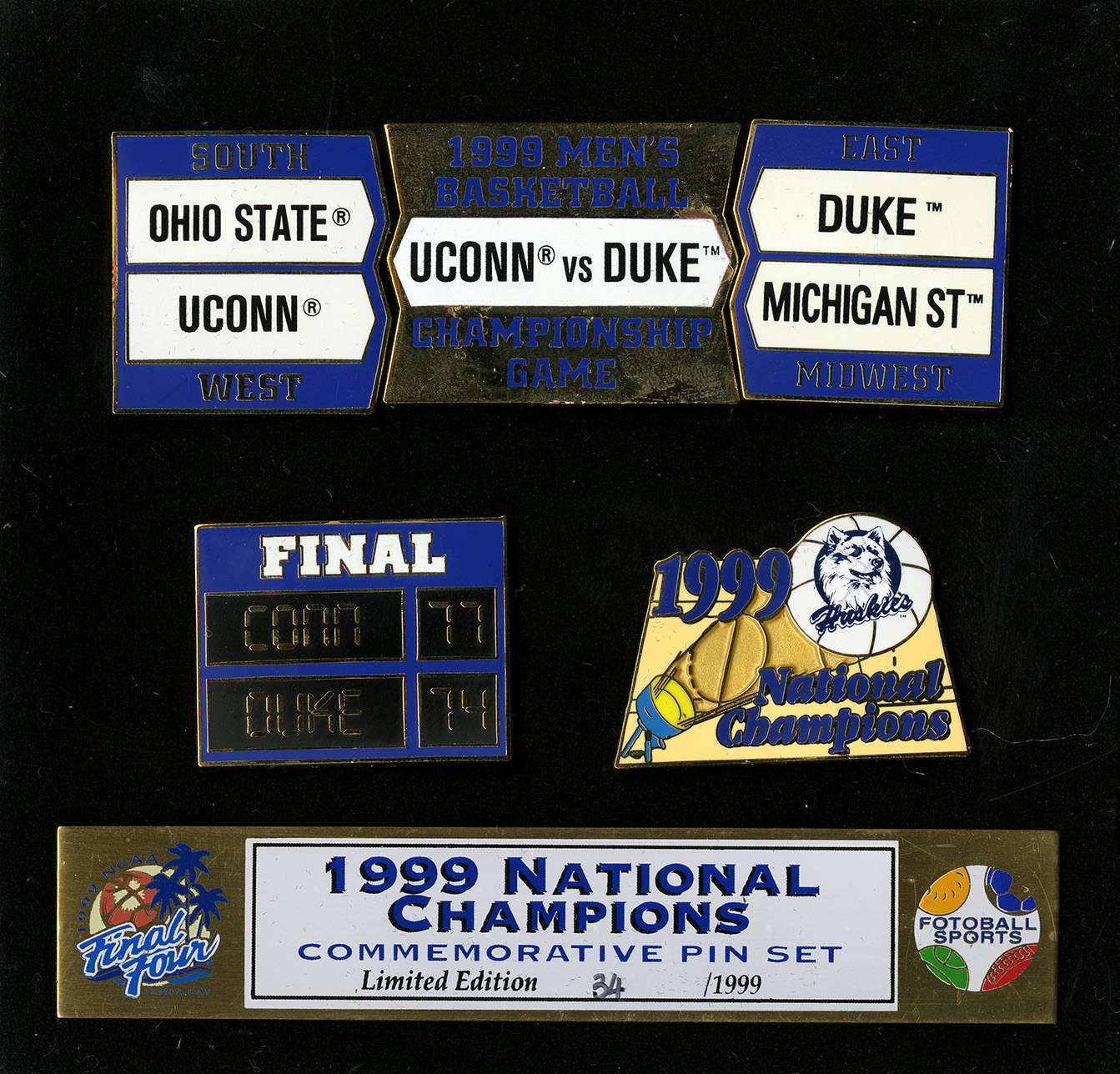

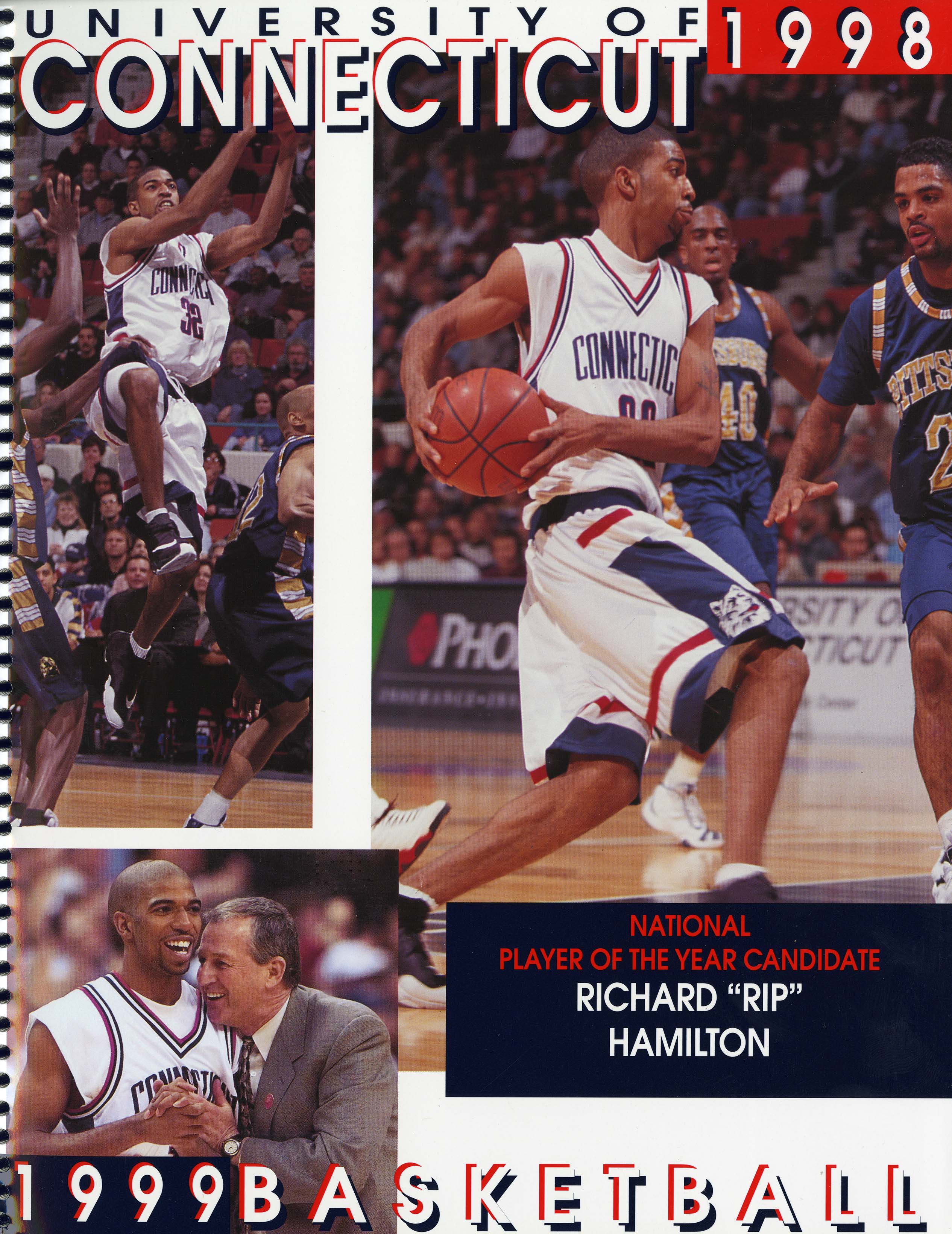

A Great Moment in UConn Athletics History: The Men’s Basketball Team’s 1999 NCAA Championship

The 1998-1999 men’s basketball season at the University of Connecticut was unlike any other. Since the arrival of Coach Jim Calhoun in 1986, the team had grown by leaps and bounds, winning an NIT title in 1990 and achieving great success thereafter. But the Huskies had yet to capture the biggest prize of all—the NCAA national championship.

From the beginning, though, the 1998-99 season looked different. The Huskies started off with a 19-0 winning streak, though injuries tripped the team up in February 1999 with losses to Syracuse and Miami. But the Huskies would remain undefeated for the rest of the season. And many of the team’s victories were hard won—nine wins came only after the team had been trailing at half-time.

Personnel was key. While college teams tend to lose players after only a few seasons, the Huskies began the 1998-99 season with its full starting line-up from the previous year: senior Ricky Moore, juniors Richard “Rip” Hamilton, Kevin Freeman, and Jake Voskuhl, and star sophomore Kahlid El-Amin. Remarkably, this line-up almost never returned. Rip Hamilton was tempted to leave UConn for the NBA after two seasons, potentially motivating his close friend Kevin Freeman to move on as well.

Yet a discussion with Coach Calhoun convinced Hamilton to change his mind, and Freeman decided to stay too, not wanting to leave his friend and teammate behind. The whole team even had a chance to strengthen their camaraderie on and off the court with an overseas trip to London and Israel during the summer.

By the time spring rolled around, the Huskies were ranked number three in the nation, and were a top seed in the West, playing the opening round of March Madness in Denver. Yet the team to beat was Duke’s Blue Devils, the top-ranked team in men’s basketball and a strong favorite to win the championship.

The UConn players got a sense of the long odds in their hotel room the night before the final game. Gathered around the television, they saw images beamed in from Durham, North Carolina, where throngs of Blue Devils fans were already adorned with championship gear. The premature victory lap pulled the team together, steeling them for the big day.

Coach Jim Calhoun, however, arrived at the championship game feeling calm and confident. While Duke’s team was impressive, Calhoun sensed his player’s experience and determination would carry them to a win. Nevertheless, things did not look so serene on the court. Duke took an early 9-2 lead and bested the Huskies at half-time with a score of 39-37.

Yet the Huskies fell into an old pattern—pushing forward during the second half toward victory. After a series of before the buzzer free-throws delivered by El-Amin, UConn ultimately beat Duke 77-74 under the dome of Tropicana Field in St. Petersburg, Florida. Many have named the March 29, 1999, championship game as one of the greatest match ups in college basketball history.

But the real show may have been the adoring crowds that greeted the Huskies when they returned home to Connecticut. A day after the final game, adoring fans lined the state’s bridges and roads to cheer as the team traveled to campus from Bradley International Airport and made the bus trip back to Storrs to greet waiting fans in Gampel Pavilion.

A victory parade around Hartford, a trip to the White House, and many other celebrations would cement the 1999 NCAA championship as an event to remember in the history of UConn sports.

For those interested in learning more about that historic season, Archives and Special Collections holds a range of materials related to the championship game, along with other collections on UConn sports. We invite you to view these materials in our reading room and our staff is happy to assist you in accessing these and other collections in the archives.

This post was written by Shaine Scarminach, a UConn History Ph.D candidate who is a student assistant in Archives & Special Collections.

“Thinking with my hands” in the Archive: Second Generation New York School Gems

Currently a postdoctoral fellow in the School of Literature, Media and Communication at Georgia Institute of Technology, Dr. Nick Sturm is an Atlanta-based poet and scholar. His poems, collaborations, and essays have appeared in The Brooklyn Rail, PEN, Black Warrior Review, The Best American Nonrequired Reading, and elsewhere. His scholarly and archival work on the New York School of poets can be traced at his blog Crystal Set. He was awarded a Strochlitz Travel Grant in 2018 to conduct research in the literary collections, including the Notley, Berrigan, and Berkson Papers, that reside in Archives and Special Collections.

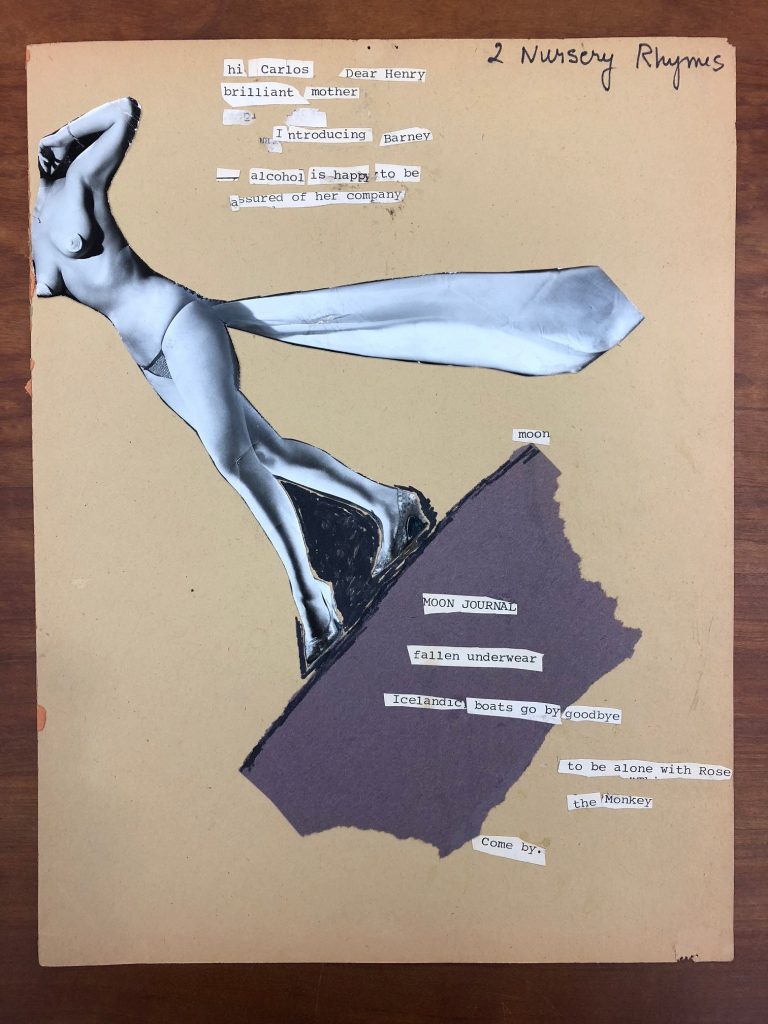

In my first-year writing course at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta where I teach as a Marion L. Brittain Postdoctoral Fellow, my students are reading books by Second Generation New York School poets to critique and creatively reimagine concepts of youth, coming-of-age narratives, and the overlap between do-it-yourself and avant-garde aesthetics. We already read Joe Brainard’s I Remember and Ted Berrigan’s The Sonnets, two versions of youth, memory, and selfhood constructed by male poets of the New York School, and were beginning to read Alice Notley’s Mysteries of Small Houses (1998) to extend this intertextual conversation about youth through the perspective of a female poet. While re-reading Mysteries, a book of autobiographical poems that tracks Notley’s “I” through the prismatic complexities of life and writing, I returned to her poem “Waveland (Back in Chicago)” in which Notley, challenged by the responsibilities and strictures of living inside concepts like motherhood and femininity in the mid-’70s, describes her process of collage-making, a practice Notley continues to be devoted to.

Frozen collection of world—this is “art” I don’t

write much poetry;

I’m thinking with my hands—a ploy against fear—

I have a pile of garbage on the floor

The poem then catalogs a series of collages with titles like “WATERMASTER” and “DEFIES YOU THE RHYTHMIC FRAME,” and also describes a collage composed of “a photo of a stripper I’ve named / Barney surrounded by cutout words she / dances to poetry.” Reading these lines, I remembered that I had actually just seen this collage in Notley’s papers at the University of Connecticut. Among a couple dozen collages by Notley, there was Barney herself, headless, cape trailing behind her, walking across a fragment of moon. After discussing this poem in class, I was able to show my students  the collage to talk about how seeing an example of Notley’s visual art helped us think about her critiques of femininity, motherhood, and aesthetics. Students were surprised that I had such an example to show them—what had seemed like a passing reference in a poem suddenly become material. They immediately started to describe the effects of juxtaposing the collage’s title “2 Nursery Rhymes” with the presence of a nearly-nude woman. They asked what it might mean for Notley to be a “brilliant mother” in association with the mythological feminine connotations of the moon. And they noted how the epistolary gesture that opens the collage’s text, “hi Carlos Dear Henry,” resonated with Berrigan’s The Sonnets, which is riddled with salutations like “Dear Marge,” “Dear Chris,” and “Dear Ron.” Seeing Notley’s collage projected in front of them, pairing the material evidence of the poem’s description with a conversation about how the visual medium supplemented their reading of the text, students said they felt a different connection to the poem, to Notley’s work, and to our entire discussion that day.

the collage to talk about how seeing an example of Notley’s visual art helped us think about her critiques of femininity, motherhood, and aesthetics. Students were surprised that I had such an example to show them—what had seemed like a passing reference in a poem suddenly become material. They immediately started to describe the effects of juxtaposing the collage’s title “2 Nursery Rhymes” with the presence of a nearly-nude woman. They asked what it might mean for Notley to be a “brilliant mother” in association with the mythological feminine connotations of the moon. And they noted how the epistolary gesture that opens the collage’s text, “hi Carlos Dear Henry,” resonated with Berrigan’s The Sonnets, which is riddled with salutations like “Dear Marge,” “Dear Chris,” and “Dear Ron.” Seeing Notley’s collage projected in front of them, pairing the material evidence of the poem’s description with a conversation about how the visual medium supplemented their reading of the text, students said they felt a different connection to the poem, to Notley’s work, and to our entire discussion that day.

Of course, none of this would have been possible without my recent visit to the archives at the University of Connecticut. Thanks to the generosity of a Rose and Sigmund Strochlitz Travel Grant, I spent a week in the papers of poets and artists like Notley, Ted Berrigan, Bill Berkson, and Ed Sanders, among others, reading voluminous correspondence with Joe Brainard, Anne Waldman, Bernadette Mayer, Lewis Warsh, Ron Padgett, and a litany of other Second Generation New York School writers. Well-known for its Charles Olson Research Collection, the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center is also home to a wealth of materials associated with the New York School and is a necessary destination for any scholar of 20th century American poetry. And though a week of nonstop work in the archive allowed me to read and assess a lot of material, the sheer amount of New York School material stored at UConn, much of which has only barely begun to be utilized by scholars, meant that I was inevitably rushing through stacks of papers, quickly unfolding and refolding letters, swiftly scanning folder titles, and scratching my own nearly incomprehensible notes in a frenzied, focused attempt to see and catalog as much as possible before having to return to Atlanta. Like Notley’s description of collage-making in Mysteries, the archive is a place where I’m also “thinking with my hands” as I arrange, photograph, and order material in “a ploy against [the] fear” of overlooking or not knowing the full extent of what’s present in the archive. Every piece of material, like in Notley’s collage, is necessary and meaningful. This is how “a pile of garbage” becomes both art and scholarship. Starting with what you touch, a life and intelligence are animated.

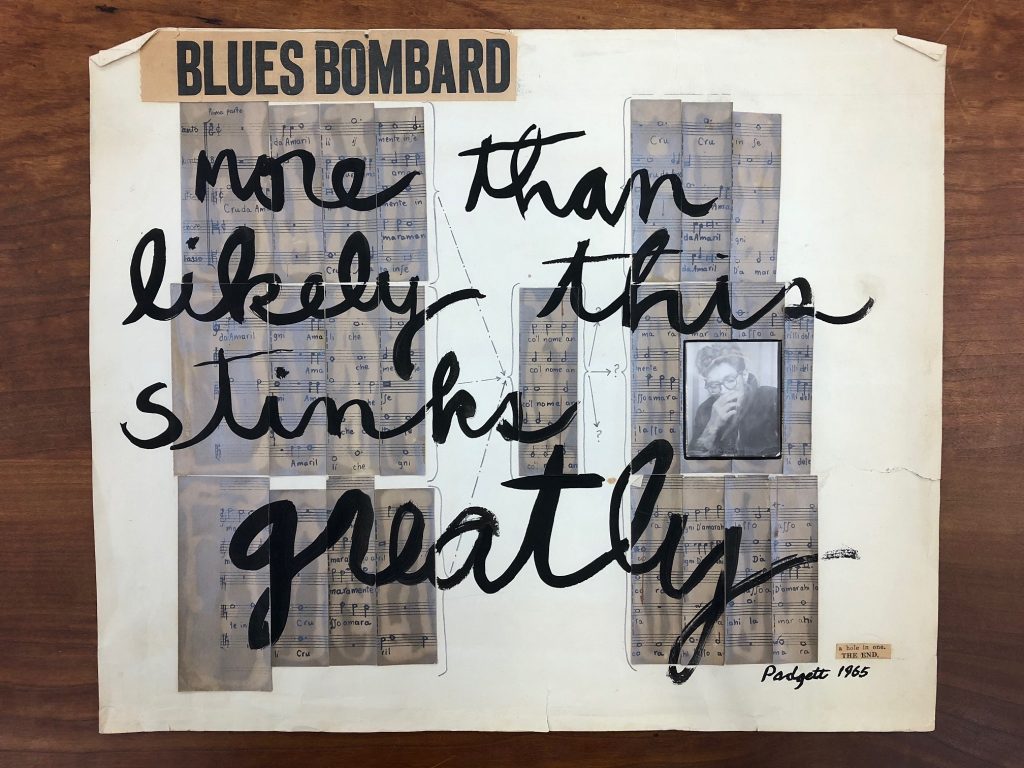

Notley wasn’t the only poet whose visual artwork is held at the University of Connecticut. Take this incredible poster-size collage “Blues Bombard” (1965) by Ron Padgett with the poet’s thick, elegant cursive painted over sliced fragments of sheet music that frame a photo booth portrait of Padgett, face half-obscured, cool, and mysterious. It’s rare to find visual artwork by Padgett that isn’t a collaboration with friends like Brainard or George Schneeman, and this piece is particularly astounding both for its size and the quick, pleasing, and humorous visual narrative that follows from the newspaper clipping-title, down across the rhyming and chiding main text ”more than likely this stinks greatly,” the arrows and question marks that logically and quizzically suggest a set of correspondences, the appearance of the artist mid-gesture, and the small, humorous, non sequitur conclusion “a hole in one. THE END.” It’s a lovely piece, and entirely Padgett in its cartoonish wit and simplicity.

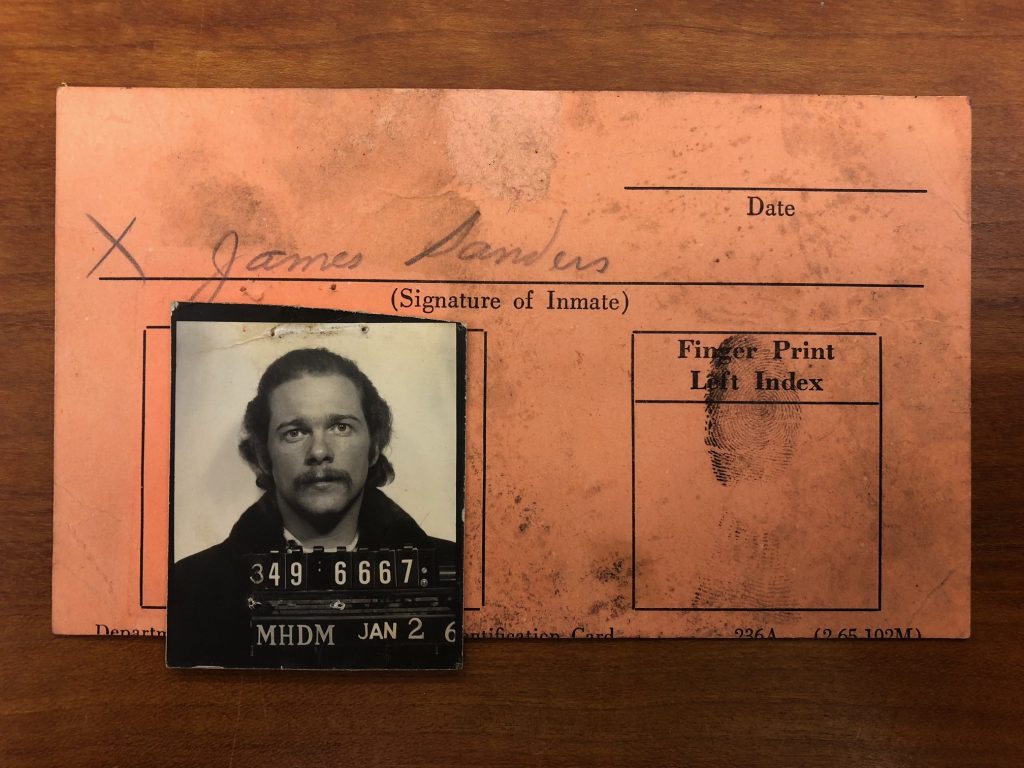

I was also interested to work in Ed Sanders’s papers at UConn, which includes a wealth of material from the Peace Eye Bookstore, the infamous “secret location on the lower east side” where Sanders’s mimeograph magazine Fuck You: A Magazine of the Arts was published from 1962-65 until the store was raided by the NYPD on obscenity charges. Incredibly enough, the collection includes both a handwritten note from 1964 instructing Sanders to call an FBI agent and Sanders’s January 1965 mugshot following his arrest. After Sanders defeated the charges against him, Peace Eye temporarily reopened in 1967 with a Fuck You-style gala event auctioning off “literary relics & ejeculata from the culture of the Lower East Side.” The collection includes the handwritten notecards Sanders used to identify the various items for sale in the auction, like an “iron used by rising young poets to iron the buns of W.H. Auden during the years 1952-1966,” “Allen Ginsberg’s Cold Cream Jars,” and a letter—likely in protest—from Marianne Moore to Sanders in response to receiving a copy of Fuck You in the mail. Some of the material actually confiscated by the NYPD in the raid of the bookstore is in the collection as well, with the police evidence identification slips still attached, like a copy of a Joe Brainard drawing described by police as “Blue colored Headless Superman drawing with private parts exposed.”

I was also interested to work in Ed Sanders’s papers at UConn, which includes a wealth of material from the Peace Eye Bookstore, the infamous “secret location on the lower east side” where Sanders’s mimeograph magazine Fuck You: A Magazine of the Arts was published from 1962-65 until the store was raided by the NYPD on obscenity charges. Incredibly enough, the collection includes both a handwritten note from 1964 instructing Sanders to call an FBI agent and Sanders’s January 1965 mugshot following his arrest. After Sanders defeated the charges against him, Peace Eye temporarily reopened in 1967 with a Fuck You-style gala event auctioning off “literary relics & ejeculata from the culture of the Lower East Side.” The collection includes the handwritten notecards Sanders used to identify the various items for sale in the auction, like an “iron used by rising young poets to iron the buns of W.H. Auden during the years 1952-1966,” “Allen Ginsberg’s Cold Cream Jars,” and a letter—likely in protest—from Marianne Moore to Sanders in response to receiving a copy of Fuck You in the mail. Some of the material actually confiscated by the NYPD in the raid of the bookstore is in the collection as well, with the police evidence identification slips still attached, like a copy of a Joe Brainard drawing described by police as “Blue colored Headless Superman drawing with private parts exposed.”

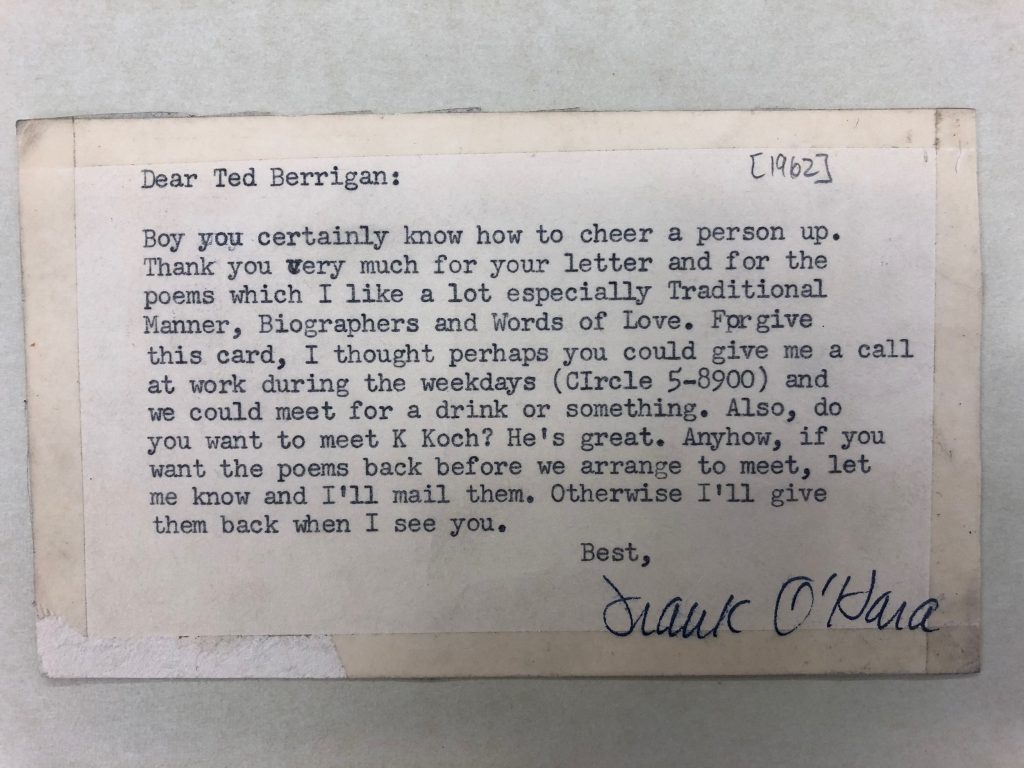

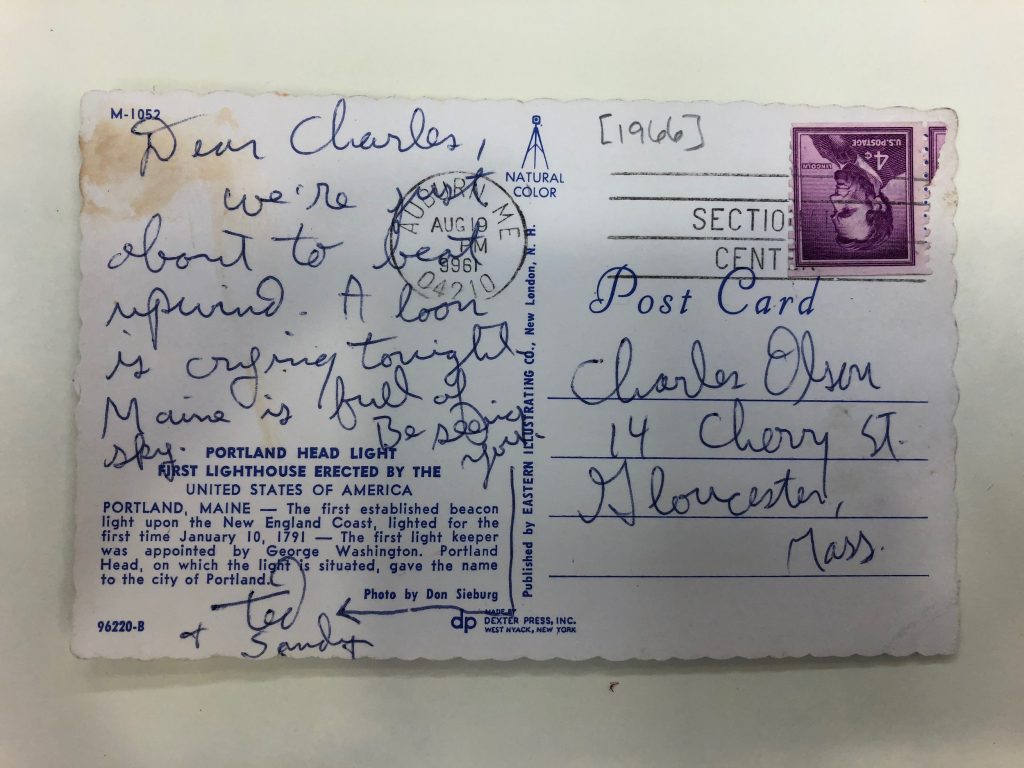

Among collages and obscenity charges, the New York School material at UConn also runs parallel to and benefits from the archive’s already well-known collections of Frank O’Hara and Charles Olson papers. The resonance of these collections is embodied in two postcards; one from Frank O’Hara to Ted Berrigan and another from Berrigan to Charles Olson. Much can be made of the micro-lineage threads of the New American poetry and New York School that run through these three poets. Not only are Olson and O’Hara canonical energies within Berrigan’s The Sonnets, but Berrigan’s self-described “rookie of the year” arrival in American poetry occurred at the 1965 Berkeley Poetry Conference, over which Olson’s presence loomed large. Additionally, O’Hara’s work had been a guide for Berrigan on how to live as a young poet. What’s great about the 1962 postcard from O’Hara to Berrigan is that it offers a reversal on the standard hierarchical narratives of literary tradition. Here, it’s O’Hara praising Berrigan’s poems as he invites him out for a drink and “to meet K. [Kenneth] Koch,” who would also be a New York School hero to Berrigan. Evidenced by the tape arranged on the edges of the card to harden and preserve it, Berrigan clearly treasured this correspondence from O’Hara, which due to the use of Berrigan’s full name, seems to have been their very first formal exchange. One images Berrigan, then 27 years old and having just moved to New York City the year before, formally expressing his admiration for O’Hara’s poems in his initial note. This postcard shows Berrigan’s first-hand devotion to his aesthetic sources. On the other hand, the August 16, 1966 postcard from Berrigan to Olson reveals an already well-established and easy going correspondence with the author of The Maximus Poems and “Projective Verse,” as Berrigan, referencing the postcard’s text on the other side, writes, “Dear Charles, We’re about to beat upwind. A loon is crying tonight. Maine is full of sky,” and signs off, “Be seeing you, Ted + Sandy.” Likely having stopped in to see Olson in Gloucester, Massachusetts on the drive up to Maine with his first wife, Sandy, Berrigan is playfully following up with the elder poet only about three weeks after the death of O’Hara.

Among collages and obscenity charges, the New York School material at UConn also runs parallel to and benefits from the archive’s already well-known collections of Frank O’Hara and Charles Olson papers. The resonance of these collections is embodied in two postcards; one from Frank O’Hara to Ted Berrigan and another from Berrigan to Charles Olson. Much can be made of the micro-lineage threads of the New American poetry and New York School that run through these three poets. Not only are Olson and O’Hara canonical energies within Berrigan’s The Sonnets, but Berrigan’s self-described “rookie of the year” arrival in American poetry occurred at the 1965 Berkeley Poetry Conference, over which Olson’s presence loomed large. Additionally, O’Hara’s work had been a guide for Berrigan on how to live as a young poet. What’s great about the 1962 postcard from O’Hara to Berrigan is that it offers a reversal on the standard hierarchical narratives of literary tradition. Here, it’s O’Hara praising Berrigan’s poems as he invites him out for a drink and “to meet K. [Kenneth] Koch,” who would also be a New York School hero to Berrigan. Evidenced by the tape arranged on the edges of the card to harden and preserve it, Berrigan clearly treasured this correspondence from O’Hara, which due to the use of Berrigan’s full name, seems to have been their very first formal exchange. One images Berrigan, then 27 years old and having just moved to New York City the year before, formally expressing his admiration for O’Hara’s poems in his initial note. This postcard shows Berrigan’s first-hand devotion to his aesthetic sources. On the other hand, the August 16, 1966 postcard from Berrigan to Olson reveals an already well-established and easy going correspondence with the author of The Maximus Poems and “Projective Verse,” as Berrigan, referencing the postcard’s text on the other side, writes, “Dear Charles, We’re about to beat upwind. A loon is crying tonight. Maine is full of sky,” and signs off, “Be seeing you, Ted + Sandy.” Likely having stopped in to see Olson in Gloucester, Massachusetts on the drive up to Maine with his first wife, Sandy, Berrigan is playfully following up with the elder poet only about three weeks after the death of O’Hara.  Though Olson himself would die in 1970, and it’s unclear if further correspondence between the two poets exists, Berrigan’s “full of sky” note to Olson again shows his sense of intimacy with the poets whose work he respected and learned from. The archive, as it often does, is showing us how lineage, tradition, and aesthetic exchange are never abstract.

Though Olson himself would die in 1970, and it’s unclear if further correspondence between the two poets exists, Berrigan’s “full of sky” note to Olson again shows his sense of intimacy with the poets whose work he respected and learned from. The archive, as it often does, is showing us how lineage, tradition, and aesthetic exchange are never abstract.

I’m looking forward to returning to the archives at the University of Connecticut to spend more time thinking through the material traces of the poets I love and study, and to continue to utilize these important and still-growing collections to illustrate the ongoing importance and value both of the New York School’s second generation gems and the pedagogical, personal, and scholarly correspondence that archives allow us to develop. “I must be making my own universe / out of discards,” Notley writes in “Waveland (Back in Chicago),” and there’s a sense of that same construction of a world in the loose, wayward ephemera of the archive. What’s most fulfilling is how the process of looking and reading in the archive is always one of presence, and often magically, of being in contact with your sources.

-Nick Sturm