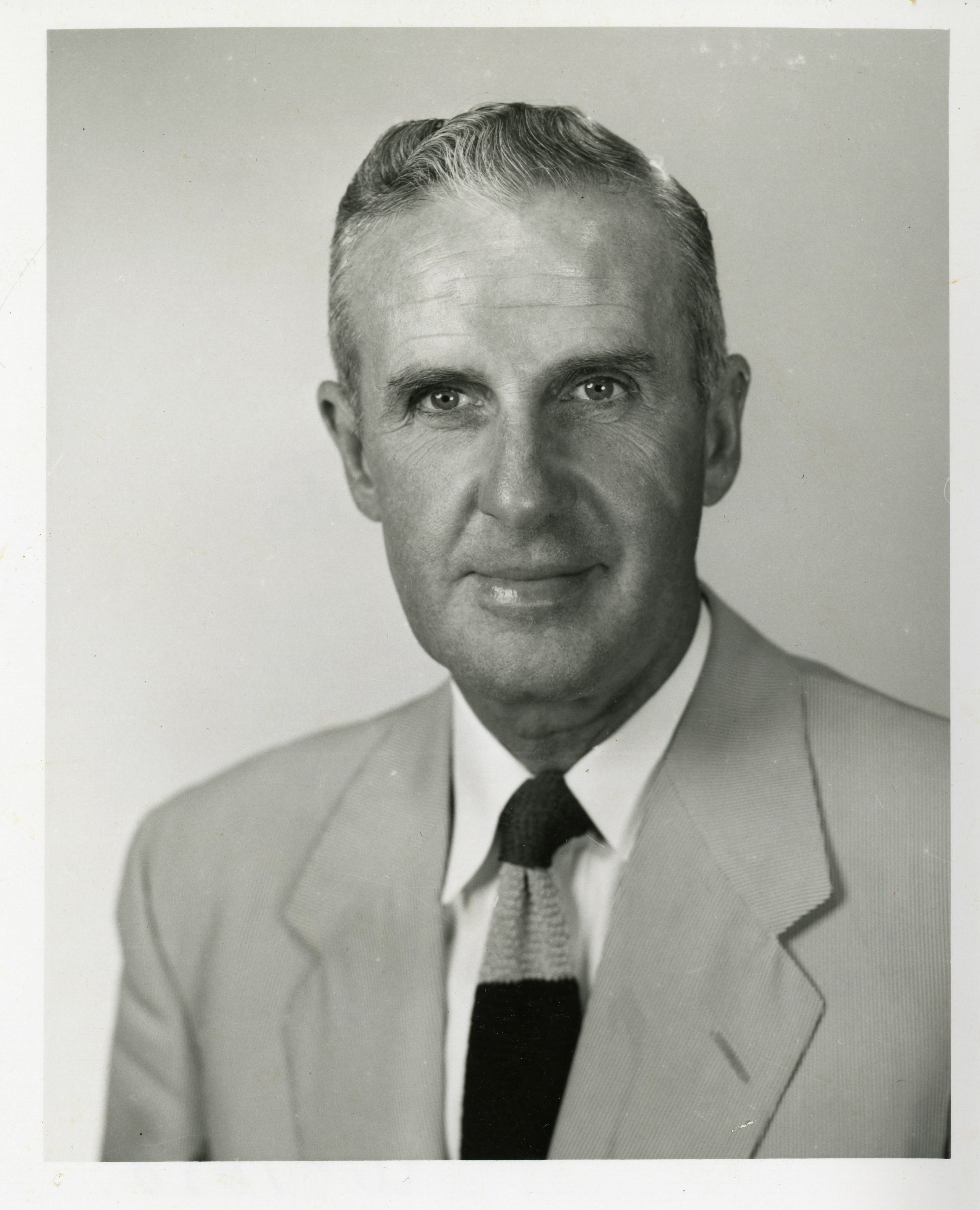

The 1998-1999 men’s basketball season at the University of Connecticut was unlike any other. Since the arrival of Coach Jim Calhoun in 1986, the team had grown by leaps and bounds, winning an NIT title in 1990 and achieving great success thereafter. But the Huskies had yet to capture the biggest prize of all—the NCAA national championship.

From the beginning, though, the 1998-99 season looked different. The Huskies started off with a 19-0 winning streak, though injuries tripped the team up in February 1999 with losses to Syracuse and Miami. But the Huskies would remain undefeated for the rest of the season. And many of the team’s victories were hard won—nine wins came only after the team had been trailing at half-time.

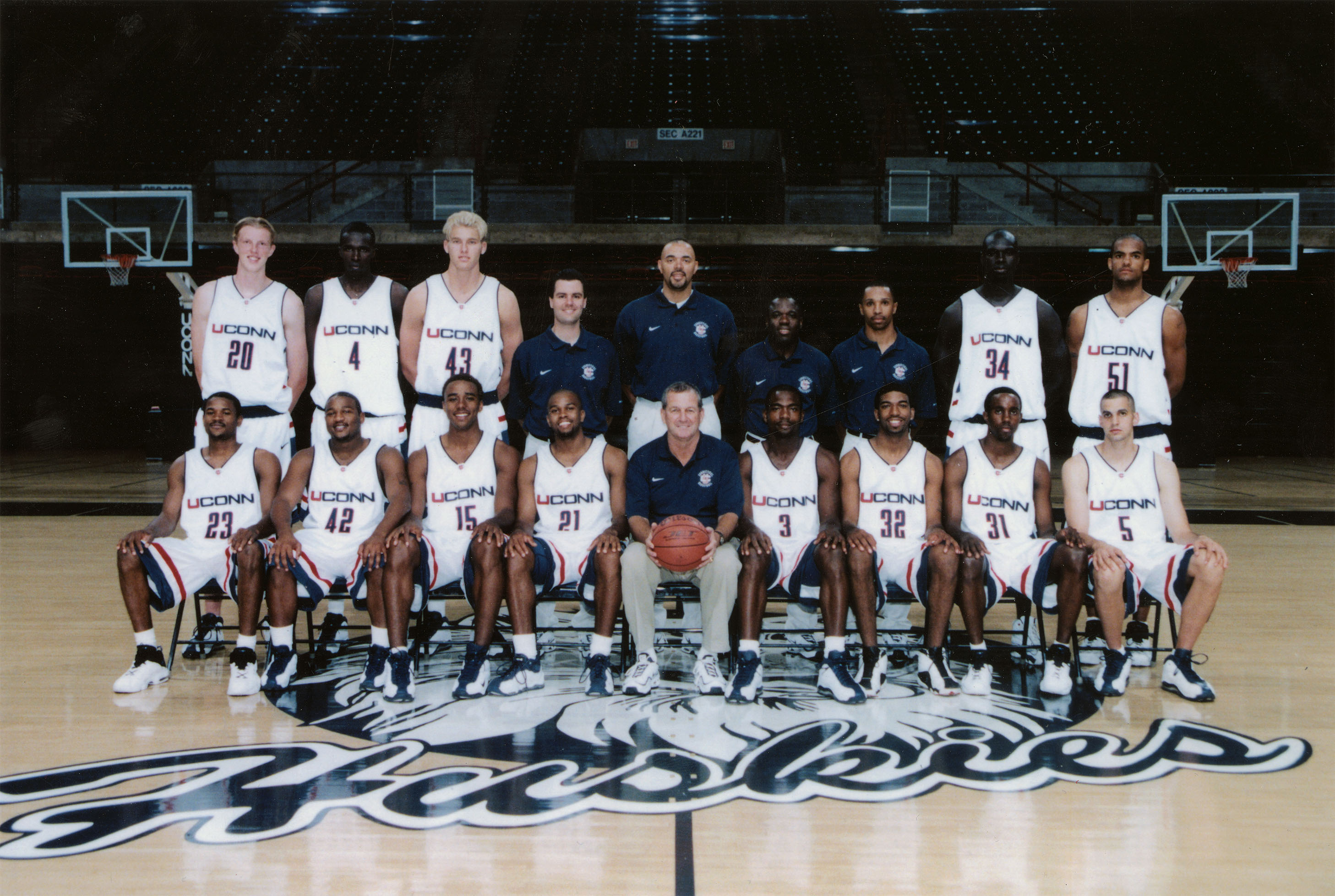

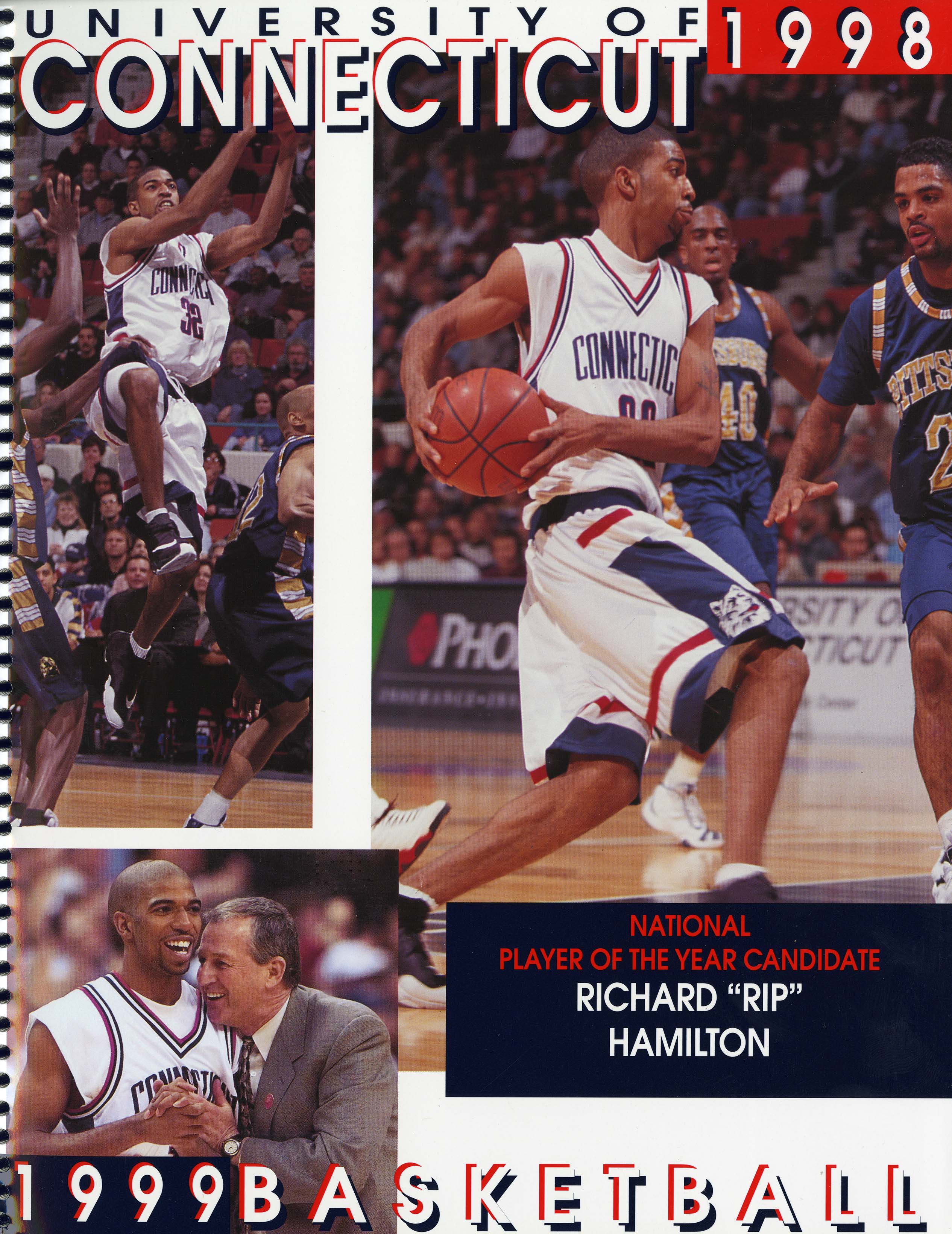

Personnel was key. While college teams tend to lose players after only a few seasons, the Huskies began the 1998-99 season with its full starting line-up from the previous year: senior Ricky Moore, juniors Richard “Rip” Hamilton, Kevin Freeman, and Jake Voskuhl, and star sophomore Kahlid El-Amin. Remarkably, this line-up almost never returned. Rip Hamilton was tempted to leave UConn for the NBA after two seasons, potentially motivating his close friend Kevin Freeman to move on as well.

Yet a discussion with Coach Calhoun convinced Hamilton to change his mind, and Freeman decided to stay too, not wanting to leave his friend and teammate behind. The whole team even had a chance to strengthen their camaraderie on and off the court with an overseas trip to London and Israel during the summer.

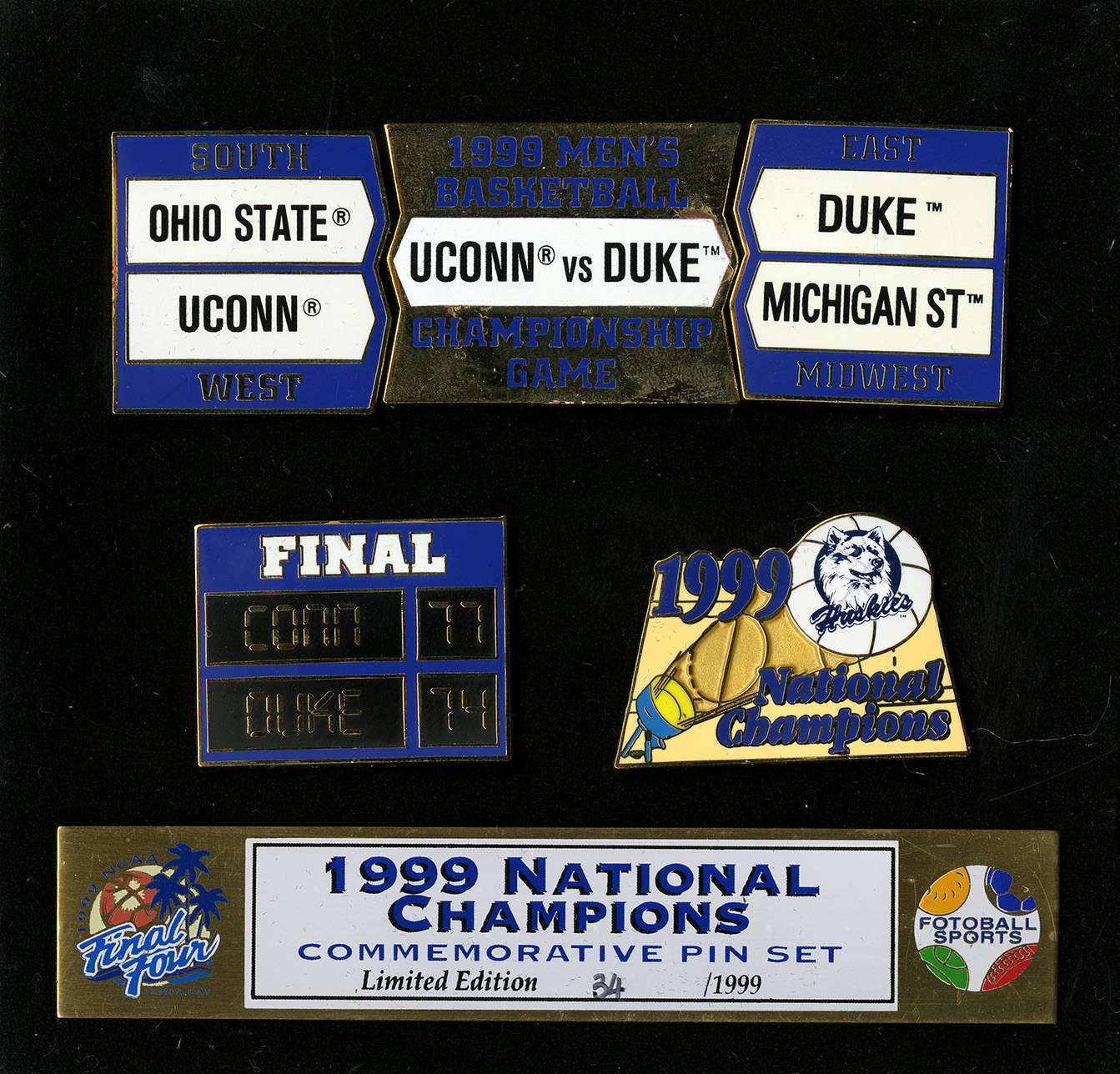

By the time spring rolled around, the Huskies were ranked number three in the nation, and were a top seed in the West, playing the opening round of March Madness in Denver. Yet the team to beat was Duke’s Blue Devils, the top-ranked team in men’s basketball and a strong favorite to win the championship.

The UConn players got a sense of the long odds in their hotel room the night before the final game. Gathered around the television, they saw images beamed in from Durham, North Carolina, where throngs of Blue Devils fans were already adorned with championship gear. The premature victory lap pulled the team together, steeling them for the big day.

Coach Jim Calhoun, however, arrived at the championship game feeling calm and confident. While Duke’s team was impressive, Calhoun sensed his player’s experience and determination would carry them to a win. Nevertheless, things did not look so serene on the court. Duke took an early 9-2 lead and bested the Huskies at half-time with a score of 39-37.

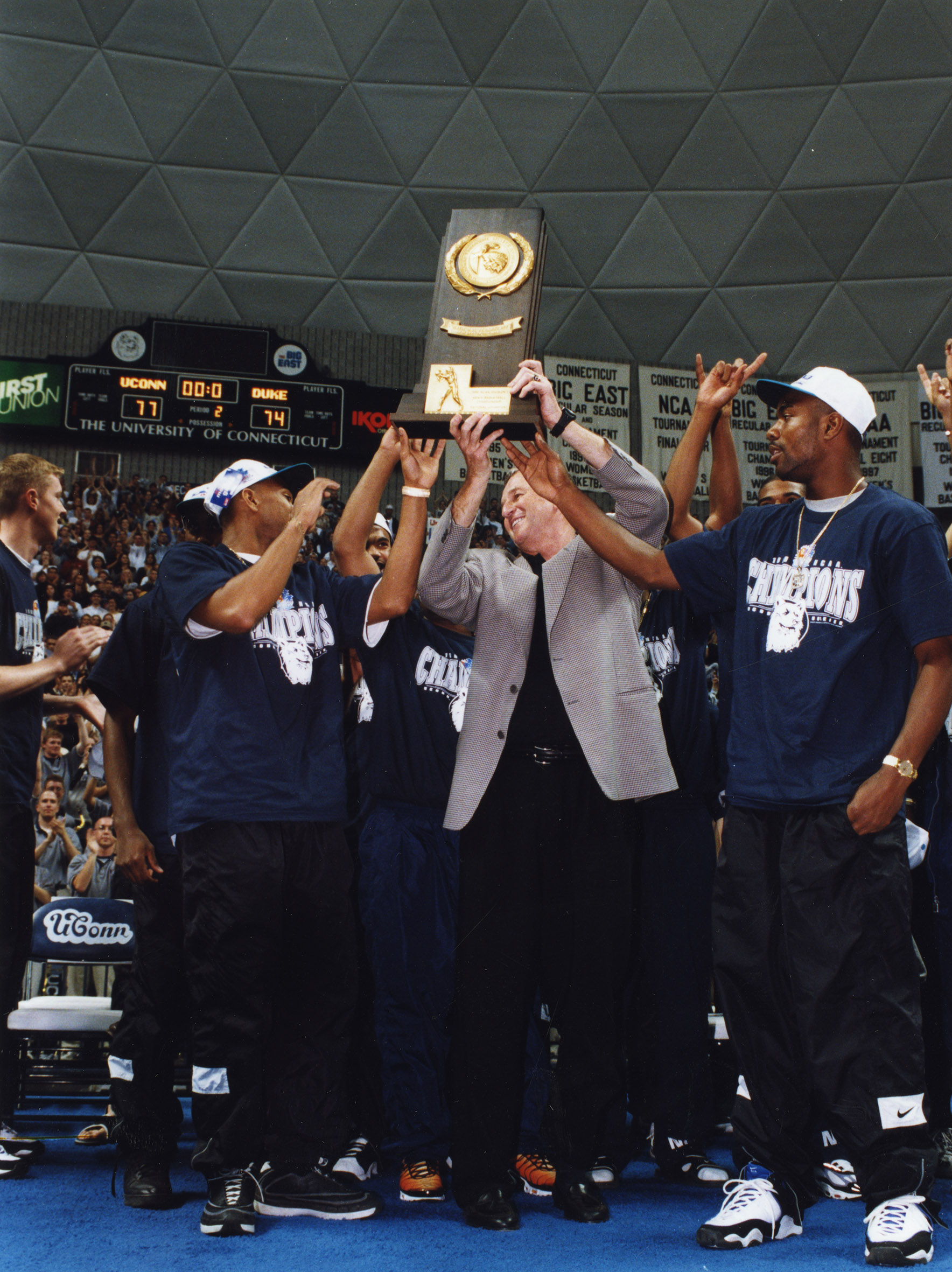

Yet the Huskies fell into an old pattern—pushing forward during the second half toward victory. After a series of before the buzzer free-throws delivered by El-Amin, UConn ultimately beat Duke 77-74 under the dome of Tropicana Field in St. Petersburg, Florida. Many have named the March 29, 1999, championship game as one of the greatest match ups in college basketball history.

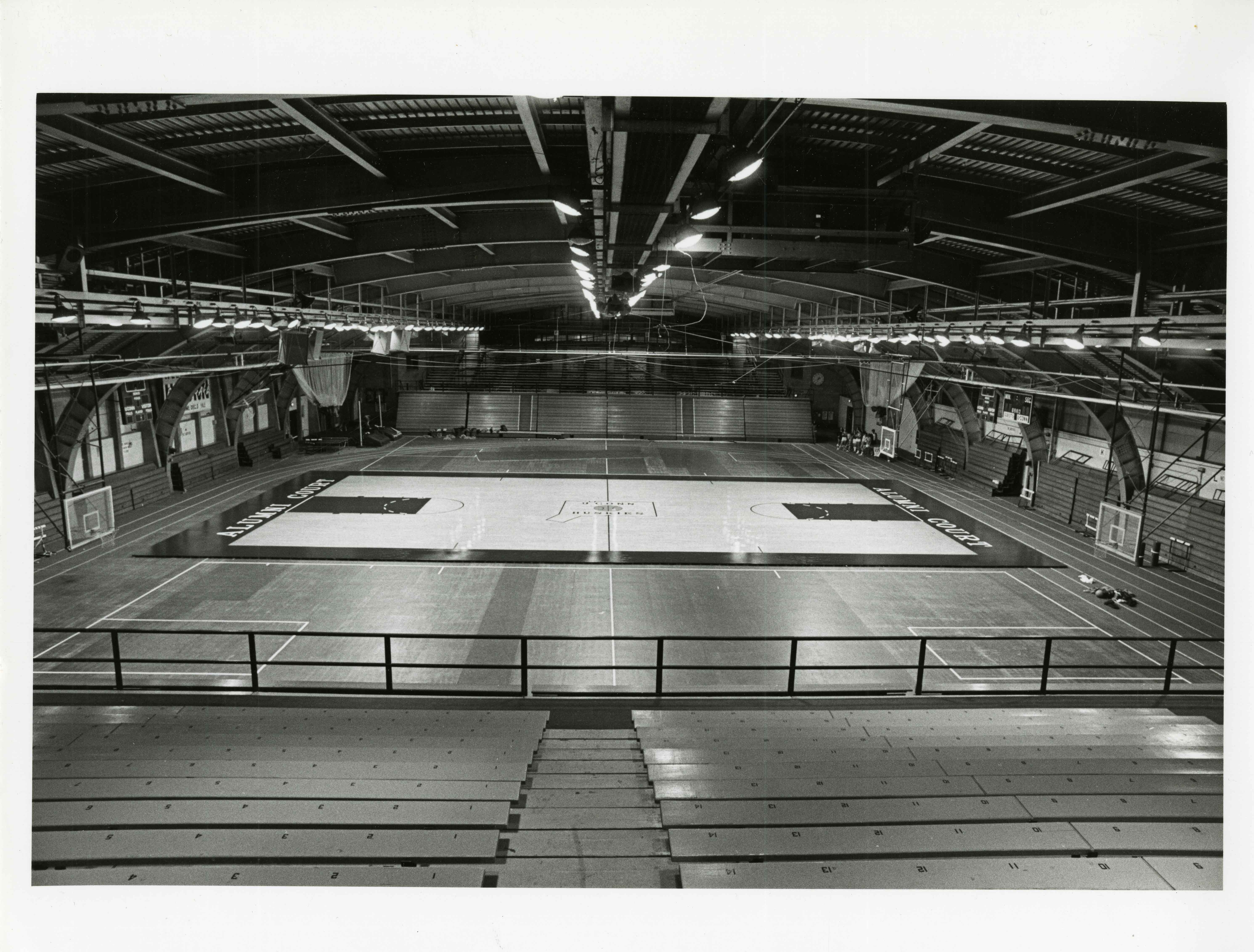

But the real show may have been the adoring crowds that greeted the Huskies when they returned home to Connecticut. A day after the final game, adoring fans lined the state’s bridges and roads to cheer as the team traveled to campus from Bradley International Airport and made the bus trip back to Storrs to greet waiting fans in Gampel Pavilion.

A victory parade around Hartford, a trip to the White House, and many other celebrations would cement the 1999 NCAA championship as an event to remember in the history of UConn sports.

For those interested in learning more about that historic season, Archives and Special Collections holds a range of materials related to the championship game, along with other collections on UConn sports. We invite you to view these materials in our reading room and our staff is happy to assist you in accessing these and other collections in the archives.

This post was written by Shaine Scarminach, a UConn History Ph.D candidate who is a student assistant in Archives & Special Collections.