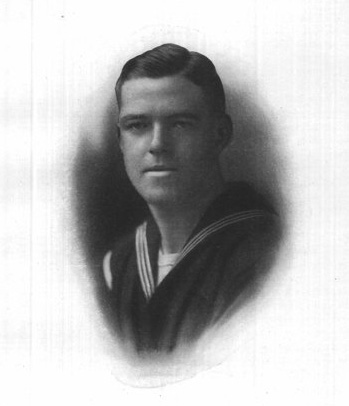

On September 27, 1919, Connecticut Agricultural College student Gardner Dow, class of 1921 and 20 years old, was looking forward to the first football game of the season, an away game to be played at New Hampshire State College. The football team and the CAC student body were particularly looking forward to the game because it signaled an end to the suspension of the team during the years of World War I. Dow, who played center, was originally not slated to play the game due to an ankle injury, but he rallied and thus traveled with the team up to Durham with high hopes of coming back to Storrs as the victors.

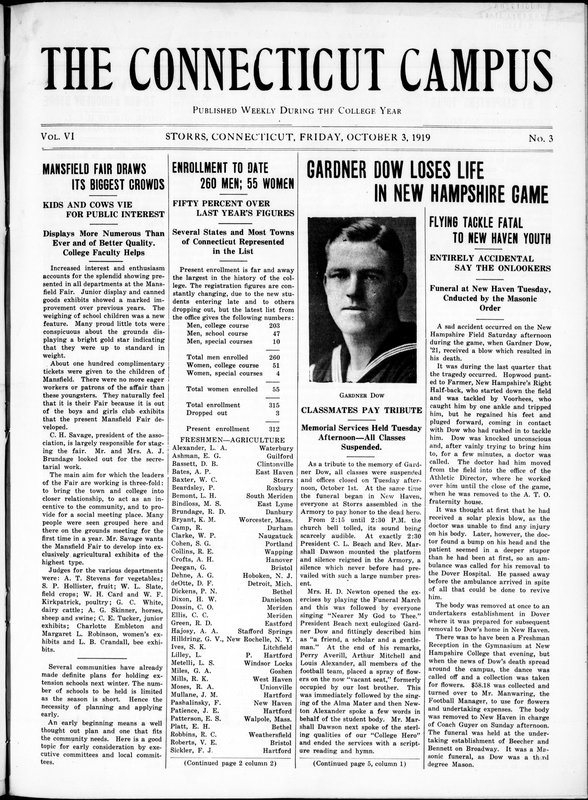

What happened at the game was well told in the October 3 issue of The Connecticut Campus, the CAC student newspaper:

“It was during the last quarter that the tragedy occurred. Hopwood punted to Farmer, New Hampshire’s Right Half-back, who started down the field and was tackled by Voorhees, who caught him by one ankle and tripped him, but he regained his feet and plunged forward, coming in contact with Dow who had rushed in to tackle him. Dow was knocked unconscious and, after vainly trying to bring him to, for a few minutes, a doctor was called. The doctor had him moved from the field into the office of the Athletic Director, where he worked over him until the close of the game, when he was removed to the A.T.O. fraternity house.

It was thought at first that he had received a solar plexis blow, as the doctor was unable to find any injury on his body. Later, however, the doctor found a bump on his head and the patient seemed in a deeper stupor than he had been at first, so an ambulance was called for his remove to the Dover Hospital. He passed away before the ambulance arrived in spite of all that could be done to revive him. The body was removed at once to an undertakers establishment in Dover where it was prepared for subsequent removal to Dow’s home in New Haven.”

The football team returned to Storrs in stunned silence, unable to believe that a treasured teammate was gone. For the next three days all activities on campus of “light amusement, ” including the Freshmen dance, were canceled or postponed while the students mourned their loss. Students took up a collection for flowers and undertaking expenses for Dow’s family.

On Tuesday, October 1, at the time that Dow’s funeral was taking place in New Haven, all afternoon classes were canceled and the entire student body, faculty and staff assembled in the Armory for a ceremony to honor Dow. President C.L. Beach described Dow as “a friend, a scholar and a gentleman.” Others spoke of “our College Hero;” the members of the football team placed a spray of flowers on a vacant seat.

Less than a week later the Athletic Association voted to name the college’s athletic field the Gardner Dow Field. The field extended from the rear of Hawley Armory westward toward what is now Hillside Road. For five decades following Dow’s death it was the home court for the CAC/University of Connecticut’s football, baseball, soccer, field hockey and track teams. By the 1970s building on campus overtook the field, with Homer Babbidge Library, the School of Business and the Information Technology Engineering buildings now on the site.

A plaque that had been placed at the field was moved to Hawley Armory, where it stands today.

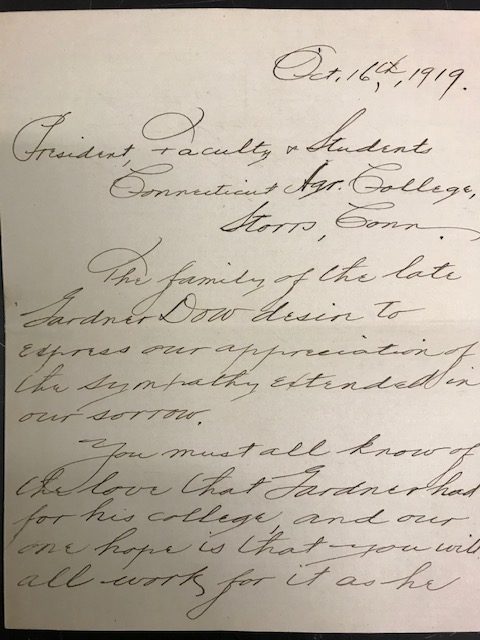

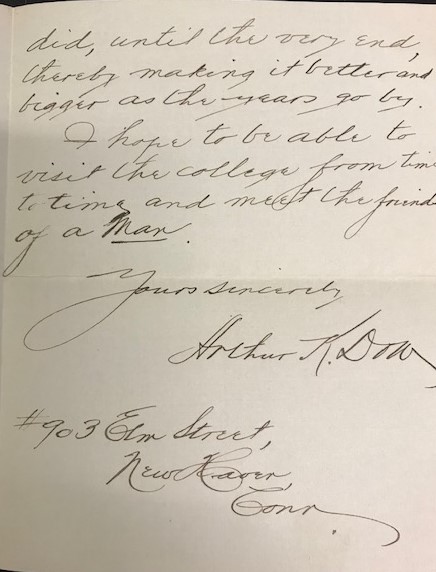

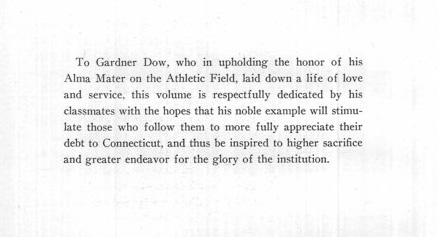

The 1920 yearbook was dedicated to Dow and the college posthumously granted him a varsity letter which was sent to his family. Dow’s father Arthur wrote to the campus community on October 16, 1919, expressing his appreciation for the “sympathy extended in our sorrow,” confirming “the love that Gardner had for his college, and our one hope is that you will all work for it as he did, until the very end, thereby making it better and bigger as the years go by.”