The official trial wasn’t scheduled to begin until November, but the interrogations were scheduled to be completed by 17 October. In addition to wrapping up with Keitel about his activities in Poland, Thomas Dodd and Father Walsh questioned General Boettcher. A frail old man and former military attaché to Washington, D.C., Boettcher had a married daughter living in Buffalo (NY), a wife and daughter missing in Russian occupied Leipzig and was questioned because he had listened to broadcasts from the U.S between 1942 and 1945. Tom later wrote to Grace, “I feel very badly for him—if he is a war criminal so am I” [p. 162, 10/8/1945].

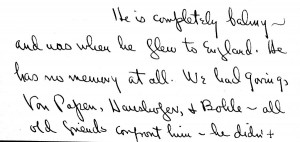

Of greater significance for the prosecutors, Rudolph Hess, Kesselring, Schacht, and a few others arrived in Nuremberg on October 8th. The former Deputy Führer, Rudolph Hess, appeared to be mentally vacant and did not recognize any of his Nazi colleagues or recollect any of the events that occurred over the last decade. Dodd wrote of Hess, “He has no memory at all. We had Göring, Von Papen, Haushofer and Bohle—all old friends—confront him. He didn’t know one of them… He has suffered a complete mental collapse” [p.163, 10/9/1945].

Adding to the confusion, “Dr. [Leonardo] Conti, one of those who worked medical experiments on concentration camp inmates, hung himself in the jail…” [p. 162, 10/8/1945]. The conjecture being that the pressure of the upcoming trial, and thoughts of what he has done in the concentration camps may have led to Conti taking his own life.

As the interrogations wound down, staff were would soon be released to return to the States. Some, including Dodd, had begun to consider potential opportunities at home. Colonel Brundage, who would be leaving Germany soon, had spoken to Tom about practicing law in Chicago. Between consideration of future employment post-Nürnberg and wrapping up the interrogations, Dodd, Major Connor, and Colonel Brundage took advantage of a brief respite and decided to visit Czechoslovakia. Taking the convertible over to Pilsen, they considered continuing onto Prague, but changed their minds once it was clear that getting the necessary permissions from the Russians occupying Prague could not be obtained in the time they had available. Dodd noted in his correspondence, “The German villages are picturesque and by contrast much more

attractive than those in Czechoslovakia” [p. 168, 10/15/1945]. Returning to Nürnberg on the evening of the 14th, Tom admitted that he “was now in one of those dead spaces mentally” [p. 169, 10.15.1945], the daily exposure to destruction and devastation both visually and through his work in interrogation exacting a tremendous toll. Tom Dodd was looking forward to the beginning of the trial because it would mean his time in Germany was coming to an end. “Be assured I will not be here for the trial itself. It will not start until December and will run for many weeks. I feel that I cannot remain here after December 1 and by that time I will have had all that this experience can give to anyone.” [p.165, 10/101945]

–Owen Doremus and Betsy Pittman

[Owen Doremus, a junior at Edwin O. Smith High School, is supporting this blog series with research and writing as part of an independent study.]

The majority of the letters from Tom Dodd to his wife Grace have been published and can be found in Letters from Nuremberg, My father’s narrative of a quest for justice. Senator Christopher J. Dodd with Lary Bloom. New York: Crown Publishing, 2007.

Images available in Thomas J. Dodd Papers.