Did you know that you may be a copyright owner and not realize it even if you haven’t published a paper? That a library included text from books in its floor with impunity?

I took the advice of my colleagues and registered with Coursera for my first MOOC, a four week professional development course on Copyright for Educators and Librarians that focused primarily on U.S. copyright. The course ran for four weeks from July 21st to August 18th.There were three instructors who all had library degrees, then went on to obtain JDs and work in the Scholarly Communication Offices at their respective universities – Kevin Smith, Duke University; Anne Gilliland, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill and Lisa Macklin from Emory University. They were passionate about what could have been a very dry subject.

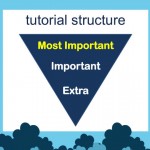

The course was divided into four units. The first three weeks had video lectures by one or more of the instructors. There were readings including selections from books by Kenneth Crews and Peter Hirtle, which served as our main textbooks. You may have heard Hirtle speak when he gave a lecture at Homer Babbidge Library last April entitled, “Living with Risk. Managing the Risk of Copyright.” We also studied the U.S. Copyright Act, sections of Title 17 of the U.S. Code, which required careful scrutiny. All readings were provided online. Students were expected to participate in the weekly forum and acquired points for posts. Then there was a quiz at the end of each week. Week 4 required a written Framework Analysis applied to a very complicated copyright situation. When the course started it wasn’t required for successful completion of the free version but during the second week the rules were changed, which did surprise me. I didn’t pay in order to use the Coursera symbol but did all the work and received a “Certificate of Accomplishment with Distinction” for achieving a high grade.

Unit 1 “A framework for thinking about copyright” covered the history of copyright going back to the king and queens of England. Queen Mary chartered the Royal Company of Stationers in 1557 and it had begun before her with the “Letters Patents”. In this unit we also learned that copyright happens as soon as the original work of authorship is fixed in a medium perceptible to the human senses. Registration is a different matter and is needed if you wish to sue in federal court.

Unit 2 “Authorship and rights” This is the unit that says you own copyright too. Students own copyright as well. Teachers should ask students permission to use their work. Some may want it kept private. Many institutions have a policy about using student work. Authorship of works for hire is a complex subject that was covered. The employer owns the rights unless it is an independent contractor in which case it should be spelled out in a signed contract. I was wondering who owns the rights to the beautiful fountain in the UConn Waterbury courtyard.

Unit 3 “Specific exceptions for teachers and librarians” I learned that the TEACH Act provides exceptions for teachers in the classroom but it does not apply to online resources, such as reserves, because reserve readings are not face to face use. Something I have become very familiar with lately due to obsolete VHS tapes that faculty still want is the Copyright Law Section 108 provision for making a copy with the notice if a reasonable effort has been made to find a replacement.

Unit 4 “Fair use” This is the part I was most familiar with but was interested in learning more as I sometimes need to evaluate the four fair use factors when posting reserve materials to HuskyCT:

1. The purpose and character of the use

2. The nature of the copyrighted work

3. The amount of the portion used in relation to the whole

4. The effect of the use upon the potential market

If you are interested in music or photography, this class covered those subjects as well. Copyright infringement of songs has been in the news lately. A song may have different copyright owners for the music and the lyrics. When you use a photo, you may need copyright permission for the building in your picture. If this course is offered again, I highly recommend it.

Works Cited

Crews, Kenneth. Copyright Law for Librarians and Educators: Creative Strategies and Practical Solutions. 3rd ed. Chicago: American Library Association, 2012. Print.

Hirtle, Peter, Emily Hudson and Andrew Kenyon. Copyright and Cultural Institutions: Guidelines for U.S. Libraries, Archives and Museums. Cornell University Library, 2009. Print.

Beilin, who shared a variety of critiques from approximately 493 responses from a survey, twitter, and the blogosphere, indicated that most librarians showed enthusiasm about the threshold concepts and felt that it was a step in the right direction. In terms of assessment, he stressed that the language was deliberately vague so that it could be tailored to particular disciplines within institutions. His criticisms of the Framework centered on critical information literacy issues of unearthing the hidden assumptions and accepted practices inherent in teaching about information. Issues like the unquestioned acceptance of “peer review” as the gold standard, awareness of unequal power and unheard voices in scholarship — these are integral to information and could be addressed in the Framework. Students need to question sources, their quality, their authority, and become more aware of how information affects their lives and how information can be a powerful force in changing their lives and affecting the world they live in.

Beilin, who shared a variety of critiques from approximately 493 responses from a survey, twitter, and the blogosphere, indicated that most librarians showed enthusiasm about the threshold concepts and felt that it was a step in the right direction. In terms of assessment, he stressed that the language was deliberately vague so that it could be tailored to particular disciplines within institutions. His criticisms of the Framework centered on critical information literacy issues of unearthing the hidden assumptions and accepted practices inherent in teaching about information. Issues like the unquestioned acceptance of “peer review” as the gold standard, awareness of unequal power and unheard voices in scholarship — these are integral to information and could be addressed in the Framework. Students need to question sources, their quality, their authority, and become more aware of how information affects their lives and how information can be a powerful force in changing their lives and affecting the world they live in.