[This summer, we at the Archives and Special Collections department at the Dodd Research Center had the pleasure to welcome Forrest Hylton, PhD, one of our Strochlitz Travel Grant awardee of this year, who came to us to do some research for his coming book, Reverberations of Insurgency: Indian Communities, the Federal War of 1899, and the Regeneration of Bolivia. Below is his essay recounting his experience working with a selection of Bolivian newspapers that are part of the Latin American Newspapers Collection. Enjoy, Marisol Ramos, Subject Librarian and Curator of the Latina/o, Latin American and Caribbean Collections]

It is always a pleasure to work in the Archives and Special Collections of a research library, and thanks to a Strochlitz Travel Grant, I came to the Dodd Center to use the Latin American newspapers collection, which is particularly strong for Bolivia in the nineteenth century. The research I did in the course of several days will allow me to analyze key features of Bolivian political culture in the years between the War of the Pacific and the Federal War of 1899 for the first chapter of a book manuscript entitled Reverberations of Insurgency: Indian Communities, the Federal War of 1899, and the Regeneration of Bolivia.

The manuscript examines sovereignty, political representation, and property rights, as well as processes of racial-ethnic and state formation, and highlights indigenous forms of organization and mobilization that combined elements from pre-colonial, late-colonial, and republican political cultures. I argue for the role that politics played in defining collective self and other, and thus for its centrality to the construction of ethnic and racial identities in late-nineteenth-century Bolivia. In the Federal War of 1899, modes of indigenous sovereignty and political representation that had been forged in anti-colonial insurrections of the late eighteenth century resurfaced with dramatic force, and victorious Liberals tarred them with the epithet of “race war.” These were non-liberal, but not separatist or ethnocidal movements, which aspired to hegemony at the sub-national level. Non-indigenous groups would be subject to indigenous authority, at least in the countryside where nine of ten Bolivians lived. Yet indigenous insurgents were firmly allied with Liberal federalists. I have used judicial sources from Bolivia to understand these aspects of indigenous insurgency.

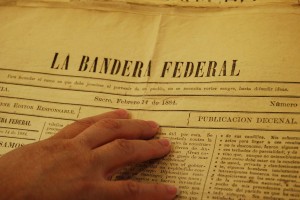

I came to Storrs to look at Bolivian newspapers from the 1880s and 90s to develop a clearer picture of the Liberal Party, in its own words and in the provinces, as well as the Conservative response to Liberal initiatives, proposals, and candidates. The Latin American newspaper collection at the Dodd Center has a number of papers, such as El Artesano Liberal, El Artesano, La Democracia, Ecos Liberales, Ecos Federales, Ecos de Aroma, El Liberal, and El Imparcial, that explicitly identified themselves as organs of the Liberal Party in Sucre, Potosí, and Oruro, as well as La Paz, and these papers—many of them produced by and for artisans—carried extensive coverage of elections of 1884, 1888, 1892, and 1896 and the fraud, intimidation, and violence that went with them, in country seats as well as provincial capitals. This coverage helps us see why the Liberal Party revolted against Conservative rule in 1899, since the electoral path to power was blocked by Conservative political monopoly, which also favored Conservative business interests in land and commerce. It also allows me to reconstruct the political and journalistic careers of leading creole figures in the Federal War, Conservative as well as Liberal, such Severo Fernández Alonso, José Manuel Pando, Ismael Montes, Fernando Guachalla, Adolfo Mier, and Claudio Quintín Barrios, and focal points of Liberal organizing in the provinces, such as Sicasica, Colquechaca, and Corocoro.

One of the remarkable things about Liberal newspapers is their interest in and coverage of local electoral efforts, particularly in Sicasica and Luribay, the area south of La Paz where the most important leaders of the Federal War emerged on the creole as well as the indigenous side. I had hoped to find news of local indigenous uprisings connected to Liberal electoral campaigns, particularly in Sicasica, but it appears that indigenous communities were largely absent from official debate and discussion among Liberals and Conservatives during the 1880s and 90s. The two articles I found in the Liberal press that mention indigenous uprisings (or the threat of them) condemned them as a threat to property rights and propertied persons, which suggests that Liberals had not seriously considered mobilizing indigenous communities until the late 1890s, even though there were local-level indigenous revolts beginning in the late 1880s.

I had expected to find evidence of Liberals and indigenous communities working together against Conservatives at least since the late 1880s, but it now looks as though indigenous activism against the privatization of community lands and Liberal opposition to Conservative political monopoly operated on largely separate tracks, with little overlap before 1896. Thus it is possible to see the Federal War of 1899 as the result of a general crisis of sovereignty, in which the convergence between indigenous movements for self-government in the countryside and the Liberal opposition based in provincial capitals and county seats—a temporary marriage of convenience—changed the country’s political geography decisively. The short-lived nature of the convergence, in turn, makes it easier to understand why Liberals turned on their erstwhile indigenous community allies immediately after coming to power.

The Dodd Center’s collection is essential for anyone wishing to understand creole and mestizo political culture of urban centers in nineteenth-century Bolivia, and though they fell beyond the scope of my own research on the 1880s and 90s, I found numerous papers from the 1860s and 70s, as well as the 1830s. What makes the collection particularly remarkable is its variety and diversity, for it contains materials from provincial capitals that have not, to the best of my knowledge, been preserved in Bolivia itself. I am grateful to have had a chance to look at the Dodd Center’s impressive collection, however briefly, and hope to return in the future.

Forrest Hylton, PhD, was a Lecturer in History & Literature at Harvard University in 2013-14, and beginning in 2014-15, he will be a Visiting Assistant Professor of History at Northwestern University.