The following post is by undergraduate and UConn History Department intern Maggie Peyton about her current project working with materials in the Archives & Special Collections.

My name is Maggie Peyton. I am a sophomore here at UConn, majoring in business. I took this opportunity to do research at the Archives & Special Collections because I am very interested in social justice and its history in the U.S. Prior to this internship, I had not taken any history classes on campus or engaged in archival work, so this is a very new and interesting experience.

My name is Maggie Peyton. I am a sophomore here at UConn, majoring in business. I took this opportunity to do research at the Archives & Special Collections because I am very interested in social justice and its history in the U.S. Prior to this internship, I had not taken any history classes on campus or engaged in archival work, so this is a very new and interesting experience.

The objective of this internship is to create an exhibit for the archives for the month of December. My fellow intern and I will be constructing an exhibit about minority women in the Civil Rights/social justice movements of the twentieth century. Specifically, I am focusing on the role of black women. What we know as the Women’s Movement was historically very exclusive and only served to represent upper-class white women. It did not acknowledge nor advocate for the issues unique to women who did not belong to this category.

Up to this point, the primary sources that I have been studying are Black Panther Community News Service Publications, largely from the late 1960’s-early 70’s. These newspapers are interesting because they provide a firsthand look at events of the time period through the lens of the Panthers, which is not a perspective that would be commonly found in a “traditional” history class. The publications are especially intriguing when examined for the presence of women in the party. The majority of articles were written about men, yet the authors were many times still women. This is illustrative of the way women too often appeared to exist in the party: major creative and active forces of movements and programs, yet consistently overlooked and put in the shadow of the panther men.

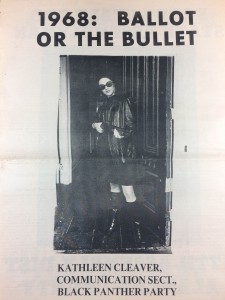

Although the major leaders and faces of the Black Panther Party were men, the publications did show that the women played an irreplaceable role. They suffered and fought for justice alongside their male counterparts. Some did attain recognition and authority within as well as beyond the party. Kathleen Cleaver was such a woman. Cleaver’s name can be seen multiple times throughout the newspapers, often with regards to international concerns for the party, particularly in Africa. Additionally, many women fought and were persecuted, but were given little acknowledgement. During the arrest of the New York 21, in which twenty-one Panthers were arrested on conspiracy charges, two women were taken in. Their names were Joan Bird and Afeni Shakur. Joan was beaten when taken in for questioning, and both were given meager, inadequate living conditions while being held in custody. This is significant because women were and still are frequently overlooked in discussions of police brutality, even by the Panthers themselves.

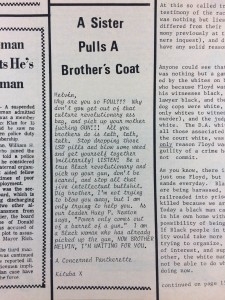

One very interesting article was specifically dedicated to dispelling notions about misogyny in the Panther movement: “We in the black Panther party do not relate to male chauvinism…many of our comrades, who are facing life imprisonment or death penalty, are women.” The article then goes on to discuss a group of 14 New Haven chapter members who were indicted for conspiracy to commit murder, 5 of whom were women. It also notes that 3 out of these 5 women were pregnant at the time. This does acknowledge the vital role that women played in the party, however does not address any specific treatment by Panther men towards women. It is not clear from these newspapers how women within the party were specifically discriminated against, which is logical seeing as the organization was male-dominated in positions of power. Still, the very fact that a member was prompted to write such a piece suggests discontent across gender lines. One can also see statements from women expressing their displeasure with the male leadership surface occasionally in the publications. One letter to the paper by a woman signed “Kituba X”, reads, “Why are you so FOUL??? /All you brothers do is talk, talk, talk, talk./As our leader Huey P. Newton says, ‘Power only comes out of a barrel of a gun’. I am a Black woman who has already picked up the gun, NOW BROTHER MELVIN, I’M WAITING FOR YOU.” This is very demonstrative of the real problem, which the male author of the aforementioned article seemed to be oblivious to: women were allowed, even expected, to fight alongside their brothers in arms, and yet their voices were not being heard and, for the most part, they did not carry the same authority as their male counterparts.

Intersectional identities are often times lost in social justice movements focused on a singular prejudice. For this reason, black and other minority women were left by the wayside with what is commonly known as the Women’s Movement. On the flip side, the Civil Rights movement for racial equality was led largely by men who were not always able to understand, let alone represent, the unique struggles faced by those at the intersection of racism and misogyny. The Black Panther Party is only one example of this system of women’s unacknowledged contributions.