Patrick Butler, Assistant Archivist for the Alternative Press Files Collection and Human Rights Collection, is a 2018 Ph.D. graduate of the UConn Medieval Studies Program. During his time as a graduate student he worked in the UConn Archives to broaden his materials handling experience and develop skills as an archivist. He has specialized training in medieval paleography and codicology.

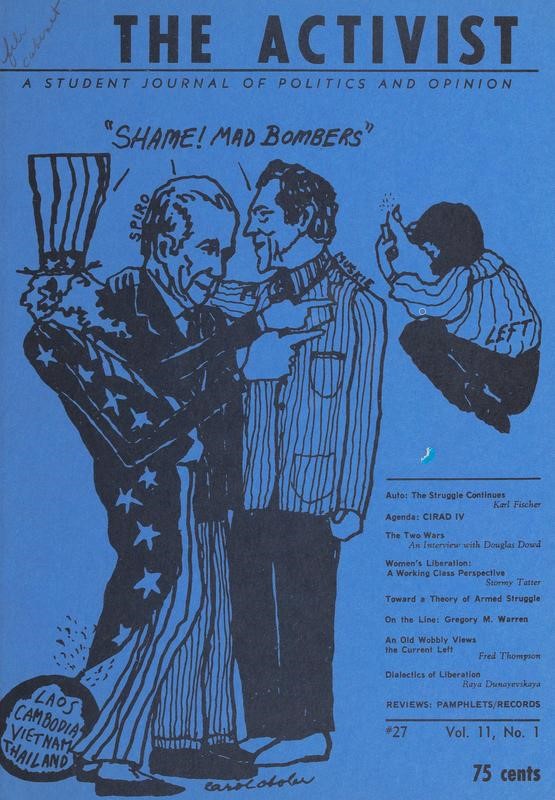

Over the past year I have been shepherding a project in order to make the APC Files Collection discoverable outside of a card catalog cabinet in the lobby of the UConn Archives. This collection consists of over four-thousand subject files of single issue publications, fliers, newsletters, comic books, and various ephemera relating to the underground press and political activism from the 1960s to the present. The ultimate goal of the project is to digitize and upload the entire APC Files collection to the Connecticut Digital Archives (CTDA).

At the moment I am uploading the first collection of scanned materials, which means this project, as a whole is entering into what could be considered its final phase. Final of course may belie the fact that it will require a tremendous amount of effort and continuing coordination to scan these materials in conjunction with the staff of the digitization lab at Homer Babbidge Library, without whom this project would not be possible.

This project has come with a new host of challenges for me as an aspiring archivist and seasoned academic, and has given me new opportunities to engage my more specialized research interests through different materials and addressing a broader audience as a result.

This large-scale project has been my first exposure to the process of metadata creation and curation. Since the over four-thousand files that make up the APC Files Collection were previously only discoverable through the use of a card catalog the first step of this project required looking through all of these files and determining how to describe them in terms of controlled vocabularies.

Building the genre and authority terms of the collection gave me a familiarity with the way that users would engage with this material from the ground up. All of the materials were given the specific subject term of Underground Press Publication, for instance, but building off of that from each subject term would help distinguish some of the materials further: Civil Rights, Socialism, World Politics, or Right-Wing Extremism are examples of a few of the additional subject search terms that would help researchers consult the collection in the future. Doing this work for each item gave me an appreciation for how these labeling practices require constant revision. I used FAST Terminology, but as I kept working with the collection I would go back and revise which term I would use to encompass the materials I was describing. Civil Rights, for instance, became a more useful term than trying to find specific terminology for each civil rights movement or locus of interest for each folder of material.

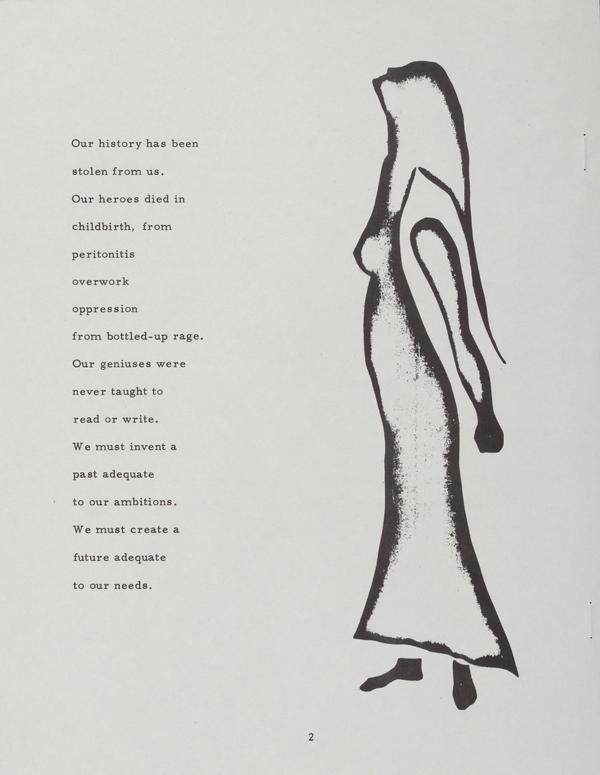

Because the technical requirements for the project require evaluating the contents of every folder on some level, I was given a unique opportunity to look at the entire collection of materials. One outcome of this was to see a connection between the interest I have in theorizing violence and vulnerability in writing centered on community building. The idea of radical vulnerability, particularly as described in the works of Judith Butler lay at the core of the work of my dissertation, but Butler’s work was something I could see resonating in a variety of Alternative Press Publications.

The journal Access is one such publication that explores the intersections of vulnerability and community building. A publication produced by the staff of UConn’s Wilbur Cross Library during the 1970’s it sought to highlight issues of racial awareness, gender equality, and environmentalism. The goals of their publication resonate strongly with my own feelings about the role of the humanities:

The new physical and ideological format of this publication reflects what we believe to be a growing awareness that librarians have certain social responsibilities as curators of ideas. Our work should not be confined to books. And fortunately, many of the WCL staff members feel a calling that begins with ideas and extends into actions. We salute those who employ their skills in the promotion of careful thought and new awareness in such areas as black culture, woman’s rights, environmental concern and political responsibility.