The following guest posts by Asst. Prof. Charlie Brover and Alumnus John Palmquist (’71) are in conjunction with the current UConn Archives exhibition Day-Glo & Napalm: UConn 1967-1971 guest curated by George Jacobi (’71). The exhibition is on display until October 25th with an evening reception on September 19th, from 6-8pm in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center.

Guest Post by Asst. Prof. Charles Brover:

My Lear year reflection: Was it pissing in the wind?

I will be 80 in September. I’m King Lear’s age. (“Fourscore and upward, not an hour more nor less”). Some 50 years ago in my course on Shakespeare’s tragedies, we talked about how much easier it was to identify with Hamlet, that flashy student on spring break from Wittenberg, than the benighted old man who hath ever but slenderly known himself. Lear began his education at 80, and one hell of an education it was—a fierce warning against the unreflected life. So now in the fifth act of my own education I am grateful to my old comrade Larry Smyle for reaching out to me and to George Jacobi and Graham Stinnett for the opportunity to reflect on those superheated days at UConn 50 years ago. Were they formative in my life? Were they just an episode of frothy anti-authoritarian rebellion?

As I search for a through-line between those stormy experiences of a young English professor fresh out of graduate school and the life-long revolutionary and unreconstructed Marxist I have become, I come back to the students. I was the Faculty Advisor of SDS. Maybe 10 years older than the students. I think I was supposed to rein them in, but…there was the war. The New Left was fond of quoting Gil Scott Heron’s lyric “the revolution will not be televised.” The war was televised—horrifying images of the bodies of soldiers and burned villagers. When it was all over, upwards of two million casualties. As an old holocaust survivor has said, sometimes you have to interfere.

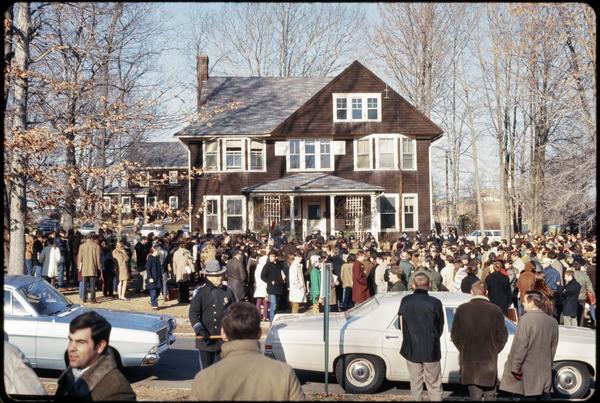

We interfered as best we could. We decorated the military drab ROTC hangar with jaunty posters and declared it a childcare center, if only for a day. We called a meeting in the morning and by evening a thousand of us would pack an auditorium for a teach-in. To this day, I am not sure how people were mobilized so quickly. No social media, no text messages on smart phones. We talked to each other. We argued. We knew and cared for each other. We stayed up all night to occupy Gulley Hall. We interrupted ROTC parades and other celebrations of militarism. We protested against the corporate recruiters who made the napalm that burned down Vietnamese villages to “save them from communism.” We mounted “guerrilla” theater productions in unlikely places that were part improv comedy, part masque, and all ridicule of the academic pomposity of the administration and most of the professoriate. We wrote and distributed the “UConn Free Press,” and roared with delight at Jack’s “Husky Handjob.”

The UConn anti-war movement displayed an inchoate anti-capitalism. We saw that the Vietnam War was not an aberration. We understood that war and racism ran deeper in U.S. political economy and culture than anything that could be fixed by tinkering around the edges. We had contempt for both capitalist parties, particularly the Democrats who were conducting the Vietnam War and lying about it. We used the word, “imperialism,” taboo among liberals.

What did I learn? Of course, I learned what everybody learned: the limitations of a student movement self-isolated from the social forces that are decisive in the historic struggle between classes. But personally I learned something else too from those young activists of SDS pin-balling around the campus and fantasizing in the Campus Restaurant. From Larry and Cassie and Ellie and Jeff and Kevin and all the rest I learned how it felt to be part of a living political movement. What’s the through line? A political movement is a living social organism. Revolutionary action is creative, joyful, a cultural festival on the side of the oppressed.

I spent my immediate post-UConn years in search of the revolutionary content of Marxism in the living movement of the organized left. In the story I tell myself about my life’s journey those early UConn experiences helped to inoculate me against the criminal reformism of Stalinism and the tepid capitalist reformism of social democracy. When the forces of capitalist reaction struck back against the radicalism of the Civil Rights and anti-war movements, the New Left dissolved and academics retreated to the relative safety of the class room, what Bryan Palmer called the post-modern “descent into discourse.” Instead, I went looking for the living movement, out onto the heath of revolutionary history and emerged an internationalist and a Trotskyist. I’m now a member of the Class Struggle Education Workers and a writer for our journal, Marxism and Education. ( http://edworkersunite.blogspot.com ) I have been a literacy worker for forty years, and I’m still teaching.

So in my Lear year, I am deeply grateful to the SDS students who helped animate my lifelong political education. And to my colleagues Jack Roach, Dave Colfax, and Johnny Leggett, who taught me that intellectual life didn’t imply quietism, that social responsibility demanded active engagement in real life political struggles. More than once I have thought that my life’s work and the revolutionary aspirations so brightly kindled on the UConn campus amounted to pissing in the wind. Maybe. Very foolish and fond old man? Certainly. But let the winds of reaction blow, howl, and crack their cheeks. I’m still upright against the wind. Balky knees, big prostate, arthritis. The ripeness is all.

Charlie Brover UConn Assistant Professor (1967-1970)

Guest Post by Alumnus John Palmquist (’71):

I don’t think about the college years very often. I do know that we were living in extraordinary times; that much I still believe. The war, the music, the energy were all so vibrant. Staying up late until 2:00 AM talking was a big part of the learning experience. I can think of a few things that lead my turn to the left.

First, alienation from mainstream America in the mid-sixties: I became alienated from my family as my parents no longer had a loving relationship and they divorced the summer after my high school graduation. Sadly, I learned that the more I stayed away from home, the better my life was. I also became alienated from the church. I tried for many years to reach out and speak with God, but he never answered back. I was forced to go to Sunday church services until I graduated high school, which I did, but that was the end of it. I have not attended another church service to this day. So, all the pillars of security that worked so well for my classmates didn’t work for me. I constantly wondered what was wrong with me.

Second, a couple of high school teachers in my senior year got me to open my eyes and question established authority. This was somewhat of a revelation and this helped me to open my mind. Everything that mainstream society fed me wasn’t necessarily the whole truth.

Third: music. I began to listen to folk music in high school: Peter and Gordon, Chad and Jeremy, Simon and Garfunkel, Bob Dylan, Peter, Paul, and Mary, and then I heard the Rolling Stones. Adios Motown, Tom Jones, Neil Sedaka, Englebert Humperdink (who were these people???). The music spoke to me. The message resonated. People three years older were listening to a completely different set of music, and it wasn’t a strong driving force in their life as my music became to me.

Fourth: the big one, the Vietnam War. I was a pacifist and saw this war as completely unjust. I didn’t like, trust, or believe either the ruling government in Vietnam or the Viet Cong. But I saw this as a civil war and America had no part in it. The loss of lives among our peers fighting over there was sickening. To this day I see those as lives lost, not lives given up in defense of our country. I never blamed the soldiers; I blamed the evil old men who sent them over there.

So, these things made me want to grow my hair long, sport a moustache, wear bellbottoms and wire-rim glasses and boots. I wanted very badly to become an individual; my strength came from within, not from society. I bought a Triumph motorcycle and rode it all around. I believed then as now, in absolute personal freedom, as long as it doesn’t harm another human being.

However, I didn’t always agree with the SDS message, never believed in any kind of Soviet style worker’s rights, the proletariat will rise up BS. I remember some of the SDS guys trying to get us to support employees at Shop-Rite or Brand-Rex in Willimantic. Those people wanted nothing to do with a bunch of long-haired hippies running around the UConn campus. For me it was all about finding a path to individual rights and pursuing what I believed was the proper path for a human being. I very vividly remember a confrontation with Young Americans for Freedom at UConn and a conversation/shouting match I had with a red-haired guy. We both concluded that we were after the same thing: freedom. Just coming at it from different directions.

John Palmquist

UConn ‘71

Hey thanks for posting these two essays Graham. I knew John really well. I too was a student in those turmoil filled years at UConn. I also wrote an essay for the exhibit but since I haven’t seen it I ‘m not sure it was on display. I look forward to reading more of the essays that you might post in the in the future.

Power to the People.

Gary Winik

I was delighted to see the awesome exhibit and to see everybody. Kudos to everyone that put it all together! Such memories! ☮️

Yes, Gary, it was also displayed – Marian & I both read it while there & I had forgotten about some of your escapades that occurred during my time away from Storrs. We did have a great reunion. but missed having you there, along with Quisto, DK & even Tiernan was missed. We all seem to be holding up fairly well for a bunch of old farts!!

Bill Zarolinski

Thanks Bill.Yes we had many escapades in those years hahaha. One that comes to mind as I read your comment happened in the summer of 1971. You me and Katie went to the Powder Ridge Musical Festival near your home in Middletown. It was the Musical festival with no music. It was banned the day of the event however there was a lot of sex and drugs but no rock and roll. If you google the Powder Ridge Musical Festival it is documented on the internet and includes numerous and very humorous picture.

Ken Sachs here,

I was at Powder Ridge too. Melanie showed up in spite of the cancellation & performed, I remember going to the medical/bum trip tent for consult to see if it was ok to do acid along with my allergy pill- they said yes & it worked out!