Louis Goddard is a PhD candidate in English at University of Sussex and describes his research experience during a visit in September as recipient of a 2014 Strochlitz Travel Grant. Travel grants are awarded bi-annually to scholars to support their travel to and research in Archives and Special Collections at the University of Connecticut.

My PhD project focuses on the prose writings of the contemporary British poet J.H. Prynne. As well as at least thirty volumes of poetry, Prynne has, over the half-century course of his career, produced a wide range of prose work, including reviews, essays, lectures and commentaries. Perhaps his most favored outlet, however, has been in correspondence. The Thomas J. Dodd Research Center holds hundreds of letters written by Prynne, the vast majority to the American poets Charles Olson and Ed Dorn, making a two-week trip to the University of Connecticut a vital part of my research as I head into the second year of the PhD.

Having read quotations from the letters in a number of existing scholarly works – notably those by my supervisor at the University of Sussex, Keston Sutherland – I thought I had a fairly good idea of what to expect from the archives: letters full of clear opinions about art and poetry, both Prynne’s and other people’s – almost crib sheets for the poems themselves, though this is an attitude that Prynne himself would certainly not endorse. Many of the letters did indeed conform to my expectations; Prynne writes to Olson, in particular, in an at times shockingly direct style, revealing his profound hopes for what, in the early- to mid-1960s, he conceived as their shared poetic project, and his equally profound disappointment when Olson began to withdraw from the correspondence as the decade progressed.

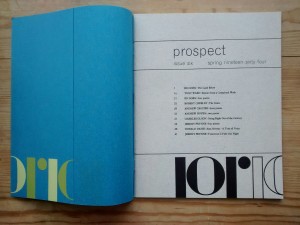

Even more interesting, however, were the aspects of the letters that I hadn’t anticipated. As part of my research, I recently completed a paper on a number of ‘little magazines’ of the 1960s, looking particularly at the legacy of Gael Turnbull’s seminal Migrant (1959–60). One of the beneficiaries of this legacy was the Cambridge-based Prospect (1959–64) – no relation of the current political magazine of the same name – which Prynne edited for its much-delayed final issue in 1964. Prynne’s opening letters to Olson and Dorn are both typed on Prospect-stamped stationery, with the younger poet tentatively soliciting work to be published in the forthcoming issue. As the correspondence progresses, the reader gets a sense of the practical and financial obstacles confronting any would-be little magazine publisher in the early ’60s, and is given insight into to the decisions which led Prynne to change the format for Prospect‘s final issue, making the magazine physically larger, removing all advertisements, and ultimately giving it away for free to interested parties.

Another aspect of the letters which struck me was the frequency of comparisons between the British and North American poetry scenes at the time, and Prynne’s efforts, both poetic and practical, to bridge the Atlantic gap. Though I had visited California and Florida as a child, arriving at Storrs involved a certain amount of ‘culture-shock’ – situated near the seaside town of Brighton, Sussex barely has an on-campus supermarket, let alone a hotel, a high school and a dairy farm (though, being British, it does have the advantage of its own dedicated railway station). I can only imagine this as the reverse of what Ed Dorn must have felt when, partly as a result of Prynne’s ministrations, he was offered a teaching post at the new University of Essex in 1965, an institution whose campus was at that point only half-built.

As well as scheming to secure fellowships and teaching positions for his American correspondents, and even offering to put up visiting poets in his rooms at Gonville and Caius College in Cambridge, the young Prynne was active in promoting new American work to mainstream British publishers. Writing to Dorn in October 1963, having received an encouraging letter from Calder Publishing about Dorn’s novel The Rites of Passage, Prynne jokes about ‘the lit. agency which I seem (& am more than pleased, as you know) to be running.’ Dorn, for his part, was skeptical – as he more or less correctly predicted in a note to Olson the previous month, ‘Prynne writes from england that he sent the novel to John Calder and go [sic] back a very favorable letter. But I’m not that dumb that I don’t dig that in 3 months I’ll get a letter from him saying they almost took it.’ When further efforts were made to place the novel with André Deutsch, not only was it again rejected, but the typescript was lost in the post, setting off a chain of increasingly irate letters from Prynne to Diana Athill.

The l etter from Dorn to Olson quoted above is part of a collection that I hadn’t originally planned to consult when applying to visit the Dodd Center, but which turned out to be one of the most fruitful aspects of the trip. Having spent some time mastering the two poets’ near-impenetrable handwriting, it was fascinating to switch from letters by Prynne to letters about him, revealing a certain ambivalence in both Olson’s and Dorn’s attitudes to the reception of their work in Britain. Similarly instructive were references to Donald Davie, the British poet formerly associated with ‘the Movement’ who played a crucial role in supporting Prynne’s early academic career and served as head of the Literature Department at Essex when Dorn first came to England. In one particularly opaque letter to Olson, Dorn shifts from an assessment of Davie – often referred to, tellingly, by his initials, ‘D.A.D.’ – to the following ambiguous statement: ‘I can’t but think of the English interest in our things other than interesting, and for myself unseful [sic], because I need to think there with them.’ Whether he meant to type ‘useful’ or ‘unuseful’ is difficult to determine, even in context.

etter from Dorn to Olson quoted above is part of a collection that I hadn’t originally planned to consult when applying to visit the Dodd Center, but which turned out to be one of the most fruitful aspects of the trip. Having spent some time mastering the two poets’ near-impenetrable handwriting, it was fascinating to switch from letters by Prynne to letters about him, revealing a certain ambivalence in both Olson’s and Dorn’s attitudes to the reception of their work in Britain. Similarly instructive were references to Donald Davie, the British poet formerly associated with ‘the Movement’ who played a crucial role in supporting Prynne’s early academic career and served as head of the Literature Department at Essex when Dorn first came to England. In one particularly opaque letter to Olson, Dorn shifts from an assessment of Davie – often referred to, tellingly, by his initials, ‘D.A.D.’ – to the following ambiguous statement: ‘I can’t but think of the English interest in our things other than interesting, and for myself unseful [sic], because I need to think there with them.’ Whether he meant to type ‘useful’ or ‘unuseful’ is difficult to determine, even in context.

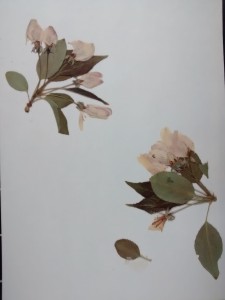

When reading correspondence fifty or more years down the line, short notes and other apparent ephemera often turn out to be more interesting than long, deliberate letters. This was certainly the case with the letters from Helene Dorn (née Buck), Ed Dorn’s first wife. In her letters to Olson, I came across a pressed rose picked not far from where I grew up in East Anglia, carried across the Atlantic, then posted to Olson’s house at 28 Fort Square, Gloucester, MA. Dorn’s two-way correspondence with Valarie Raworth, meanwhile, could have served as the basis for an entire PhD thesis on the unenviable position of ‘poet’s wife’ in a ’60s artistic scene no less patriarchal for its avant-garde credentials. Dorn often writes to Raworth with a real weariness about her day-to-day tasks, typing up her husband’s work from near-illegible manuscripts while simultaneously looking after the children and keeping their house in Pocatello, Idaho.

During my time in Storrs, I was lucky enough to stay at the Altnaveigh Inn, where there were few such household obligations to distract me – dating from 1734, the inn is known locally for hosting Olson while he taught a course at the university in the autumn of 1969. Writing this account back in London, I could wish for at least another two weeks at UConn, exploring letters from the less famous members of the Dorn-Olson correspondence nexus. But as Lytle Shaw of New York University pointed out when I met him briefly at the Dodd Center, working in archives is a bit like shopping – even if you arrive with a fixed plan, you’re as likely as not to leave with something completely unexpected.

– Louis Goddard