Within the archive of books, recordings, sheet music, letters, audiovisual materials, and advertising materials assembled by Samuel Charters are the compositions and recordings produced by contemporary blues-based musicians including John Fahey. Rare recordings released on Fahey and Ed Denson’s independent record label Takoma Records, dating from the founding of the record label in 1959, together with Fahey’s later releases, reside in Series IIB of the Samuel and Ann Charters Archives of Blues and Vernacular African American Musical Culture. Here, Samuel Charters remembers his first encounter with John Fahey and later, with his instrumental and compositional style:

Within the archive of books, recordings, sheet music, letters, audiovisual materials, and advertising materials assembled by Samuel Charters are the compositions and recordings produced by contemporary blues-based musicians including John Fahey. Rare recordings released on Fahey and Ed Denson’s independent record label Takoma Records, dating from the founding of the record label in 1959, together with Fahey’s later releases, reside in Series IIB of the Samuel and Ann Charters Archives of Blues and Vernacular African American Musical Culture. Here, Samuel Charters remembers his first encounter with John Fahey and later, with his instrumental and compositional style:

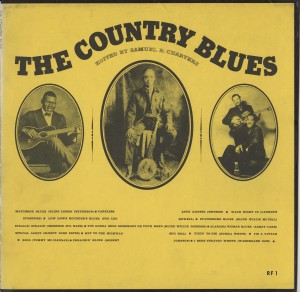

In the summer of 1959 an LP came in the mail to the basement apartment in Brooklyn where I had just finished writing The Country Blues. The record was in a white cover, with only the words “Blind Joe Death” in large letters on both sides. With it there was a letter to me from someone named John Fahey, telling me that this was a record he had made of his own music, and asking me for an opinion. The letter was as guarded as the LP jacket. The music was a series of guitar instrumentals based on the finger picking style of the Mississippi bluesmen. I kept waiting for someone to sing, and when I didn’t hear any singing I wrote John a short note saying that other people in New York were doing

the same kind of thing but the record was interesting. John has never forgiven me for my note, and even if I’m not sure if we ever would really have become friends I have always been angry at myself for my insensitivity. John sent out a few copies of the record, which he had pressed for himself on his own Takoma label, and sold more through mail orders.

When the copies were gone he recorded a new record and sold the copies the same way. This time the copies went more quickly, and he recorded a third album. Within a few years Fahey and his music had become one of the growing influences of the 1960s. He was still almost unknown personally, but his music was everywhere in the new underground.

I had difficulty describing the pieces when I first heard the 1959 album, but I soon realized that John had created a new music, based entirely on the materials he had learned from the country blues. He had been one of the people who rediscovered Bukka White, and then Mississippi John Hurt, and from the musicians themselves he had absorbed finger techniques and new concepts of guitar tunings and chordal structures. He has never described himself as a guitarist – his description of his own music is that he is a composer who plays the guitar. What he did was to create a compositional style which synthesized elements from the entire range of rural southern string music, including the Mississippi slide guitar, Virginia string bands, the alternate thumb picking of the Delta, and the finger style of the Carolinas. His compositional technique was to record passages with different guitars which built up segments of his pieces – then he spliced the tape sections together, editing, changing tone, and adding echo effects. His last step was then to learn the piece as it was finally structured so he could perform it.

By the middle of the ‘60s John was touring regularly, and he had outgrown the small record company he had set up with a partner, ED Denson, the man who had gone to Memphis with him to find Bukka White. I had known ED for several years and we worked together to sign John to a contract with Vanguard. There were two albums – the first an album that included three long requia, and an extended three part piece that utilized a complicated sound montage over John’s guitar. We recorded many of the sound effects for the montage at Knott’s Berry Farm outside of Los Angeles, where the events John was depicting in the composition had taken place. Because of time problems and delays from John’s side I finally went ahead and mixed the sound piece without him, and our edgy relationship became even more difficult.

For the second album on the Vanguard contract he worked with a friend, Barry Hansen, in Los Angeles, while I acted as executive producer in New York. The album, The Yellow Princess, was one of John’s finest achievments, with a music concrete piece built on montage, a successful fusion of his guitar with small instrumental groups, and a rich collection of new compositions.

By this time Fahey had a series of disciples, among them Leo Kottke, who developed the idiom John had created into a more flamboyant and emotionally open statement. John was not upset. He recorded Kottke for his own record company, and they continued to be close friends. He was also having emotional problems, and his life often veered into difficulties, despite the growing creativity of his music. By the 1970s an entire school of guitar composition had grown from his work, and a new record company, Windham Hill, was established by a guitarist named Will Ackerman to present young guitarists playing in the Fahey style. It isn’t an exaggeration to say that John’s guitar compositions were the basis for the New Age movement that swept the guitar world, and that the basic foundation for all of it was southern blues guitar.

The series A Language of Song features the words of Samuel Charters and the recordings he produced as preserved in The Samuel and Ann Charters Archives of Blues and Vernacular African American Musical Culture at the University of Connecticut. The series is a tribute to the great Samuel Charters – poet, novelist, translator of Swedish poets, and renowned scholar of the blues, jazz, and musical culture of the African diaspora. Samuel Charters died on March 18 at the age of 85.