The following is a guest post by Matthew Carr, PhD candidate in the Political Science Department at Columbia University studying American politics, specifically institutions, political parties, and judicial politics. In 2016 he was awarded a Strochlitz Travel Grant to further his research using the political papers in Archives and Special Collections.

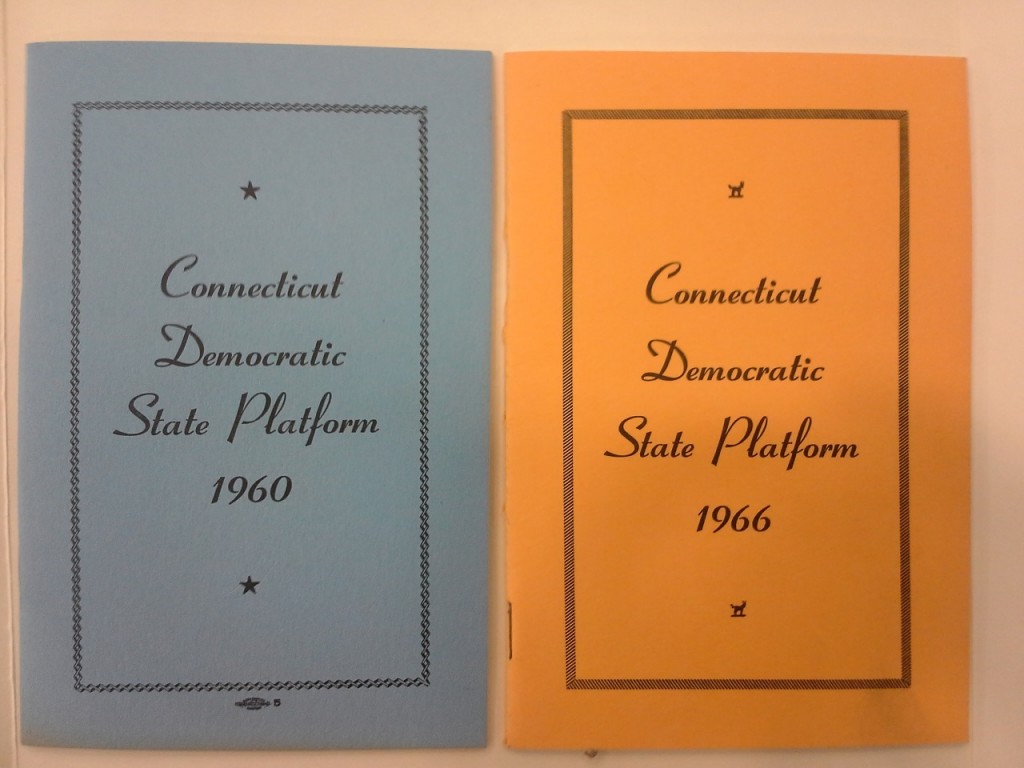

I was able to spend a few days searching the rich collection of political papers in Archives and Special Collections at the Dodd Research Center for an often neglected document – state-level political party platforms. Every four years, the national Democratic and Republican parties issue lengthy platforms, explicating their policy goals and objectives. However, the Democratic and Republican parties of the 50 states issue their own, independent platforms. While the historical national platforms are well-preserved and somewhat well-known political documents, the state party platforms are almost ephemeral and have never been systematically preserved. Although the most recent state party platforms are readily available on the party websites, the goal of myself and my fellow researchers is to locate all state party platforms from 1960 until present.

I was able to spend a few days searching the rich collection of political papers in Archives and Special Collections at the Dodd Research Center for an often neglected document – state-level political party platforms. Every four years, the national Democratic and Republican parties issue lengthy platforms, explicating their policy goals and objectives. However, the Democratic and Republican parties of the 50 states issue their own, independent platforms. While the historical national platforms are well-preserved and somewhat well-known political documents, the state party platforms are almost ephemeral and have never been systematically preserved. Although the most recent state party platforms are readily available on the party websites, the goal of myself and my fellow researchers is to locate all state party platforms from 1960 until present.

Since most state parties issue a new platform every two years, the enterprise of collecting all of them entails finding hundreds of (usually elusive) documents. Locating them presents several challenges. Chief among these is that, unlike many other documents related to politics and the policy making process, state governments do not archive party platforms. Therefore, in order to find them we have turned to a variety of sources. We initially thought that the state parties themselves might be the best preservers of their own history, but we quickly found that the parties rarely maintain any significant archives. There are encouraging exceptions; a handful of party offices maintain an attic or storeroom that serves as an informal archive with decades’ old documents. On the other hand it is a distressing experience being just a few years too late, which must be all too familiar to archivists and others concerned with historic preservation. Some parties told us that they once had a large collection of old platforms, but that – during the latest office move or a spring cleaning a few years earlier – they were purged. We have therefore turned to other sources to find the documents. A small percentage of the platforms are given a call number and placed on a library shelf, and we attained those through interlibrary loan. We have also directly reached out to those currently involved in politics and received some platforms from long-term activists  who happened to keep them.

who happened to keep them.

Archives and manuscript collections, however, have been by far our most fruitful source of platforms. The hope is that a politician, political activist, or political observer attained a copy of the platform (e.g., through being directly involved in the platform drafting process at the state convention that produced the document or simply by being given one by the state party) and kept it in his or her records. Given that the Archives’ at the Dodd Research Center is the premier repository of the papers of Connecticut political figures, searching its collections was essential in our effort to attain Connecticut platforms. Thanks to the Strochlitz Travel Grant, I was able to take a few days searching through the papers of Connecticut’s political luminaries. The Center has a rich political collection, housing the papers of senators (Prescott Bush and Thomas Dodd) and members of the House (Robert Giaimo, Stewart McKinney, Sam Gejdenson, and Nancy Johnson, among others). Although I found platforms among those collections, the most valuable source for the purpose of locating the documents I am looking for was the collection of the lesser-known Herman Wolf. He ran a public relations firm and was heavily involved in politics. Fortunately, he saved several state platforms – and for both parties, which is rare as most collections heavily document only one party or the other. Another particularly valuable resource was the collection of Audrey Beck, a state legislator who had a penchant for holding onto the platforms.

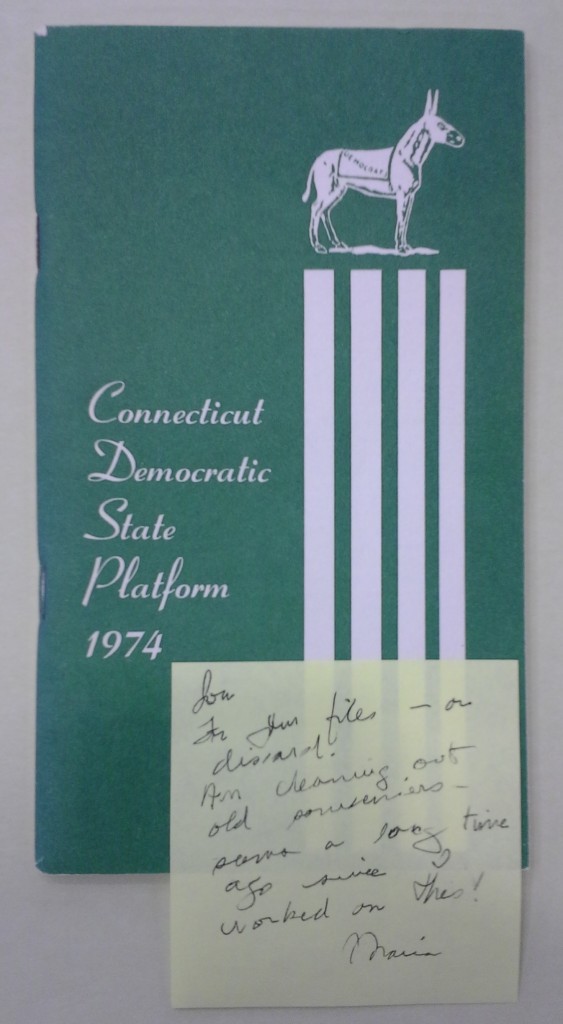

Searching the papers illustrated the array of record-keeping practices, even among similarly situated political figures. Some collections are vast with a wide variety of documents, and other collections are smaller, even though the donor had a lengthy career. In short, the individual discretion they each had was on full display, and it was, of course, nice to encounter large collections with donors who were inclined to keep a wide variety of documents (including platforms!). I found clear evidence that some documents survived only by the skin of their proverbial teeth. The picture of the 1974 Democratic platform showcases this, as the original post-it note, with discussion of whether to keep or discard the document, is still attached.

Searching the papers illustrated the array of record-keeping practices, even among similarly situated political figures. Some collections are vast with a wide variety of documents, and other collections are smaller, even though the donor had a lengthy career. In short, the individual discretion they each had was on full display, and it was, of course, nice to encounter large collections with donors who were inclined to keep a wide variety of documents (including platforms!). I found clear evidence that some documents survived only by the skin of their proverbial teeth. The picture of the 1974 Democratic platform showcases this, as the original post-it note, with discussion of whether to keep or discard the document, is still attached.

Culling through literally hundreds of feet of political documentation requires calculation in order to efficiently find what you’re looking for. Here, the collections’ finding aids, describing the contents of each box, are invaluable. But when a single collection contains thousands of documents, it is impossible for the finding aid to have extreme specificity. Therefore, to get a full sense of exactly what’s in the collection, one really needs to take some time to go through the boxes in person. Thankfully, my trip to Storrs was successful in that I found several platforms. However, we’re still searching for the Connecticut Democratic platforms for 1988, 1992, 1996, and 2000, and looking to confirm that the Connecticut Republicans stopped making platforms in 1974. The collections at the Dodd Research Center provided us with a firm foundation to eventually acquire a complete set of Connecticut platforms.

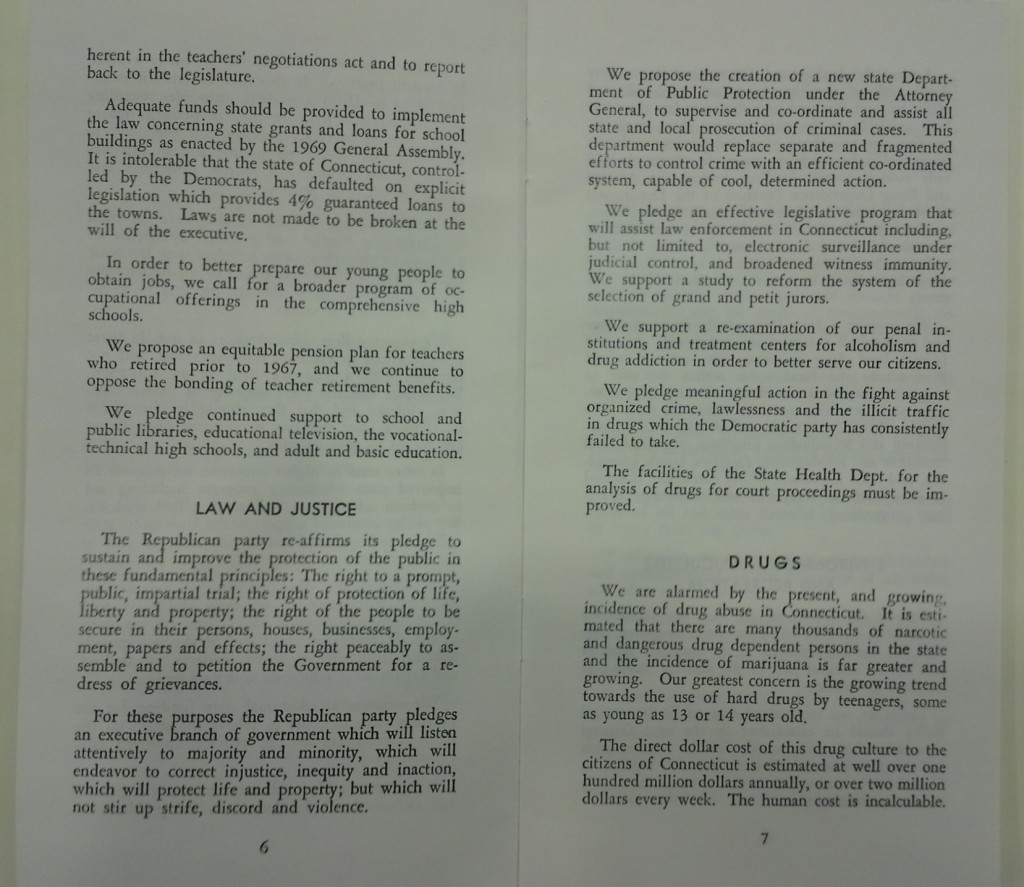

A lone state platform might be mildly interesting to those deeply invested in political history, but, frankly, the historical appeal and value of a single state party platform is limited. However, the entire corpus of state-level political platforms offers a rich documentation of political history and partisan belief which can help us better understand several phenomena highly relevant to the field of political science: the emergence and dispersion of political issues, the extent to which  the state parties differ from each other and their national counterparts, and the polarization and nationalization of the two parties. Some might expect these documents – crafted by politicians and political activists – to be stereotypically sparse and platitudinous. However, they tend to run several pages and offer highly specific policy recommendations on a diverse set of issues, including agriculture, criminal law, constitutional rights, transportation, education, and immigration, among many other topics. Therefore, we are hopeful that a systematic hand coding of these documents will allow for a better understanding of America’s two party system and the evolution of policy goals.

the state parties differ from each other and their national counterparts, and the polarization and nationalization of the two parties. Some might expect these documents – crafted by politicians and political activists – to be stereotypically sparse and platitudinous. However, they tend to run several pages and offer highly specific policy recommendations on a diverse set of issues, including agriculture, criminal law, constitutional rights, transportation, education, and immigration, among many other topics. Therefore, we are hopeful that a systematic hand coding of these documents will allow for a better understanding of America’s two party system and the evolution of policy goals.

– Matthew Carr