This post was written by Shaine Scarminach, a UConn History Ph.D candidate who is a student assistant in Archives & Special Collections. All images are from issues of the Connecticut Daily Campus and the Nutmeg, the student yearbook.

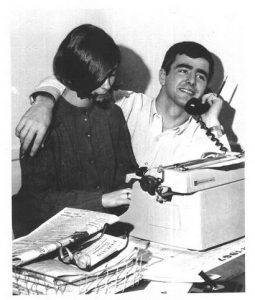

In January 1968, Dennis Hampton, a twenty-year-old philosophy major at the University of Connecticut, spent his winter break thousands of miles from home in the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon. As editor-in-chief of the school newspaper, the Connecticut Daily Campus, Hampton went to report on the U.S. war in Vietnam. The conflict occupied the minds of many students that year. In the following months, protests against the war would rock the UConn campus. But by then, Hampton had already seen the conflict up close.

After a Pan American flight over half the globe, Hampton disembarked at Saigon’s Ton Son Nhut airport. Stepping off the plane, his first view of the city surprised him—it seemed so ordinary. European cars and bright new motorbikes clogged the roads, the clamor of people and car horns filled the humid air, and the refuse of urban life lined the streets.

Only “a few odd touches” hinted at the reality—Saigon was at war. Hampton noted the grills on bus windows for deflecting grenades, the street-corner guard stations stacked high with sand bags, and the endless American military and civilian personnel. Still, the war seemed far away.

Hampton disliked Saigon. He found the city too crowded and noisy, and his first night left him feeling discouraged. What should he do and how would he do it? Why would he leave his friends and family to wander alone in a foreign city, and on his vacation no less? “I wondered what I was proving,” Hampton later wrote, “whom I would impress by coming to a country when practically everyone else did everything possible to stay away.”

Hampton had better luck away from the capital. He left Saigon by military helicopter, flying low over rice fields and canals of coffee-colored water. He touched down in Can Tho, a city southwest of Saigon. The pace was slower there, and the streets less snarled by traffic.

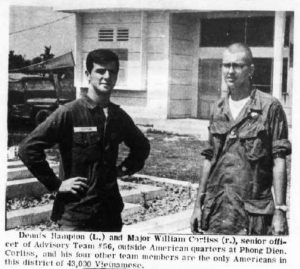

Hampton soon met Major William Corliss, a resident of Gloucester, Massachusetts, who had taught in the ROTC program at UConn’s Hartford campus before enlisting for a tour of duty in Vietnam. Hampton reported that Corliss “was impressed that a college student would spend time to come to Vietnam, and maybe just a little glad to see someone from UConn.”

In South Vietnam, Corliss served as senior commander to an American advisory team. He oversaw the small village of Phong Dien and promised to show Hampton the community development work underway there. Corliss and Hampton boarded a military jeep and took off. Hampton felt elated. He was finally “on the track of SOMETHING.”

As the pair reached Phong Dien, Hampton noted the lack of U.S. personnel in the area. He had arrived in “an actual, un-Americanized Vietnamese town.” Village life had ground to a halt because of the fast approaching celebrations of Tet, the Vietnamese New Year. Hampton spent his first day in town meeting local officials, drinking tea, and enjoying regional dishes.

The excitement would have to wait until that evening. Hampton spent the night with the U.S. military detail stationed in the village. Earlier in the day, Corliss had warned him about an impending mortar attack. Hampton wrote that he was “just a little nervous, a little afraid, but also eager.”

That changed once he heard the first mortar round go off around 11:00pm. He quickly became “a lot more nervous and afraid.” Luckily, his fears were unfounded. Hampton learned the next morning that the boom of mortars had come from U.S. troops firing in the opposite direction.

The next day, Corliss took Hampton on a tour of the surrounding hamlets. The commander spoke at length about the prospects and problems of community development. They had made some strides in education and local government but faced setbacks too. Hampton pointed to the lack of healthcare and sanitation in the area as a particular challenge. But Corliss was optimistic about his work. Community development, he claimed, would win the war.

This optimism seemed to rub off on Hampton. The college student found his time with Corliss the most informative part of his trip. It would not last. Hampton noted that he left Phong Dien only a day before the Tet Offensive, a major turning point in the war. Thereafter, the American public’s support for the war plummeted, never to recover.

Archives & Special Collections holds several collections that provide information about the Vietnam War era and its impact on campus and in society. You can find the finding aids to the following collections in our digital repository:

- Crisis at UConn, Alternative Press Collection

- Diary of a Student Revolution — a National Educational Television documentary showing the dramatic behind-the-scenes struggle between President Homer D. Babbidge and the UConn protesters demonstrating against on-campus employment recruiting by Dow Chemical Company on the Storrs campus.

- Hoffman Family Papers

- Poras Vietnam War Memorabilia Collection