“All of my pictures are created against a background of music. More often than not, my instinctive choice of composer or musical form for the day has the galvanizing effect of making me conscious of my direction. I find something uncanny in the way a musical phrase, a sensuous vocal line, or a patch of Wagnerian color will clarify an entire approach or style for a new work.”

-The Shape of Music, Maurice Sendak, 1964

…

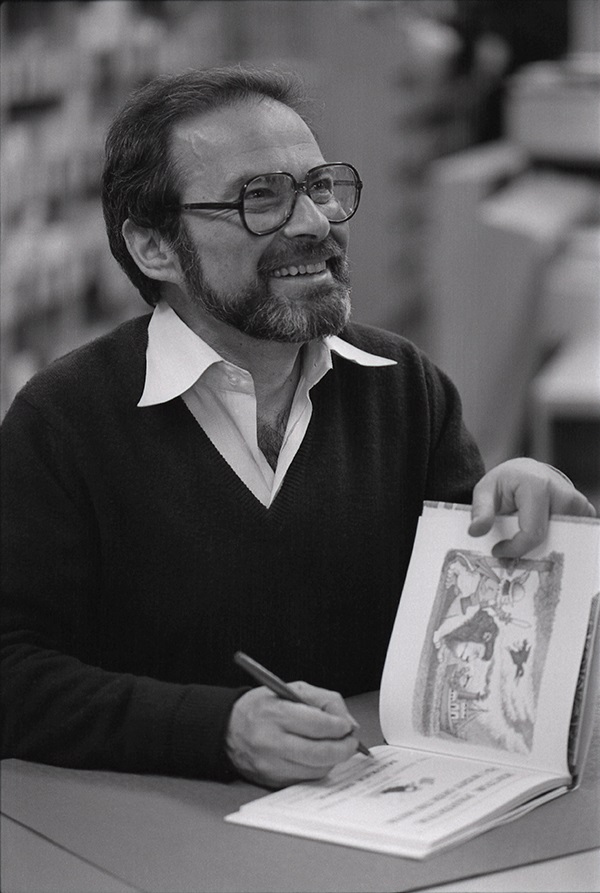

Maurice Sendak, celebrated and renowned author and illustrator of children’s books such as the revolutionary 1963 Where the Wild Things Are and 1970 In the Night Kitchen, held a life-long and deeply intimate and interwoven relationship with music. Holding in high esteem composers such as Wolfgang Amadeus Wolfgang and Franz Schubert, he was in the habit of listening to music while working on his creations, and often, references to music crept into his preliminary and final drawings. A significant example occurs in the artwork for the 1981 Outside Over There.

Musically inspired and layered with resounding personal overtures, Sendak was already working on Outside Over There when stage director Frank Corsaro asked him in 1978 to design the costumes and sets on a production of “The Magic Flute” for the Houston Grand Opera. A catalyst for the creation of Outside Over There, Sendak explained: “In some way, Outside Over There is my attempt to make concrete my love of Mozart, and to do it as authentically and honestly in regard to his time as I could conceive it, so that every color, every shape is like part of his portrait. The book is a portrait of Mozart, only it has this form-commonly called a picture book. This was the closest I could get to what he looked like to me. It is my imagining of Mozart’s life.”[i]

In the 1964 essay, The Shape of Music, Sendak describes in beautiful terms the definition of “quicken” as it relates to illustration and animation and that to him to quicken “suggests a beat-a heartbeat, a musical beat, the beginning of a dance.” In other words, to “quicken” is to bring life into the inanimate – a source of rhythm so that a picture grows alive in the flow of imagery, color, and shape, or more succinctly, music in physical form. Outside Over There follows Ida, a young girl bearing the brunt of responsibility for caring for her baby sister while her father is away at sea and her mother immobile from melancholy. While music, or rather the act of Ida playing on her wonder horn and neglecting to attend to her sister, helps to cause the kidnapping of the baby by the goblins, music is the tool or action which redeems Ida. For by playing on her wonder horn, Ida drives and melts the goblins away and results in the siblings’ reunion and reconciliation.

Sendak acknowledged that “right in the middle of Outside Over There, everything turned Mozart. Mozart became the godhead.”[ii] Dully, Mozart is seen in profile during the children’s return journey from “outside over there,” omnipresent to the scene and story but in shadow across the river in his Waldhütte, the creative cabin in the woods that becomes a recurrent Romantic theme for Sendak.[iii] In the final artwork for Outside Over There, for some drawings Sendak included not only notations for the creation dates, but also, the exact music which helped to inspire his illustrations. For example, for the artwork for page 13, a scene where Ida is playing the wonder horn and an ice baby is substituted by the goblins for the real child, the notation reads “Dec. 28, 77-Dec 30, 77 (tracing & inking)-Jan. 2, 78-Jan. 18, 78.” Above these dates, “string quartet in C- Mozart” is written in pencil. Mozart, by way of this inscription, receives his due acknowledgement as muse.

Outside Over There, after Where the Wild Things Are and In the Night Kitchen, is heralded as the final book in a trilogy of “variations of a theme” in which children cope with the day-to-day pressures of life by way of fantasy.[iv] Maurice Sendak, in speaking of Ida, says, “What she did is what I did and what I know for the first time in my life I have done. The book is a release of something that has long pressured my internal self. It sounds hyperbolic but it’s true; it’s like profound salvation. If for only once in my life, I have touched the place where I wanted to go, and when Ida goes home, I go home too.”[v] If Sendak’s love of Mozart helped to guide the textual and visual feel of Outside Over There and Ida’s journey, it is the underlying touch of the intangible which roams within the other world only to finally return home and perhaps, it is this element which ultimately touches the images and “quickens” them within their physical boundaries.

…

A curated playlist is available on Spotify based on notes made by Maurice Sendak on final drawings on deposit at UConn Archives & Special Collections. Follow the link to listen: https://open.spotify.com/playlist/3YCXQ975xKzXhsWZ4aciG3?si=nrc-j7aKR7i5O0TZ8MYRjw

[i] Jonathan Cott, Pipers at the Gates of Dawn: The Wisdom of Children’s Literature (New York: Random House, 1983), 74.

[ii] Steven Heller, ed., “Maurice Sendak,” in Innovators of American Illustration (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1986), 81.

[iii] John Cech, Angels and Wild Things: The Archetypal Poetics of Maurice Sendak (Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995), 218.

[iv] Heller, ed., “Maurice Sendak,” 81.

[v] “Sendak on Sendak as Told to Jean F. Mercier,” Publishers Weekly, 10 April 1981, 46.