This guest blog post is written by Aidan Brueckner, a graduating honors student majoring in Digital Media and Design, and minoring in Human Rights which he completed an internship for at the Archives & Special Collections in the Spring Semester of 2021. Aidan’s descriptive work can be found in the Alternative Press Collection online.

It is no secret that youth activism is on the rise. Across the world, demonstrations

occur for myriad reasons related to racial justice, climate change, drug control, and

countless more key issues. Not only are these matters far-reaching across all aspects of

society, touching on numerous disparate sectors, but the apparent frequency of social

justice events is increasing quickly as well. The push for recognition and change from a

world that has proven unforgiving and unfair is picking up steam. Naturally, college-age

students tend to be a large portion of the ones driving these agendas, as the nature of

college itself encourages collaboration and a drive to excel, as well as an increased

emphasis on critical thinking. Most importantly, however, college allows students to

collect as a group of like-minded individuals, and presents them with an opportunity to

make their voices heard. UConn is no exception, having had a well-documented history

of activism on campus from its inception. Much of this activism is contained within the

Archives, and this semester I had an opportunity to explore and evaluate some of it.

One notable item held by Archives and Special Collections that I had the pleasure

of reviewing was Ahimsa; a student-produced magazine that served as the newsletter of

Students For Peace. This issue got its start back in 1982 with the Students For Peace

branch of Eastern Connecticut State College (later renamed to Eastern Connecticut

State University), but eventually grew to become distributed at the UConn campus as

well under its Students For Peace organization. The publication does not have an

editorial stance, and encourages the submission of any and all written work so long as it

advocates for peace. The most frequently addressed topics include nuclear

disarmament, the cold war, and US Imperialism. Appropriately, the title “Ahimsa”

translates to a word meaning “non-violence” in Sanskrit. Our collection includes

numerous issues of Ahimsa, but even more are missing, which indicates prolific

publication. Reading through the file, I was able to identify several consistent

contributors as well, with some lasting past the typical four-year overturn.

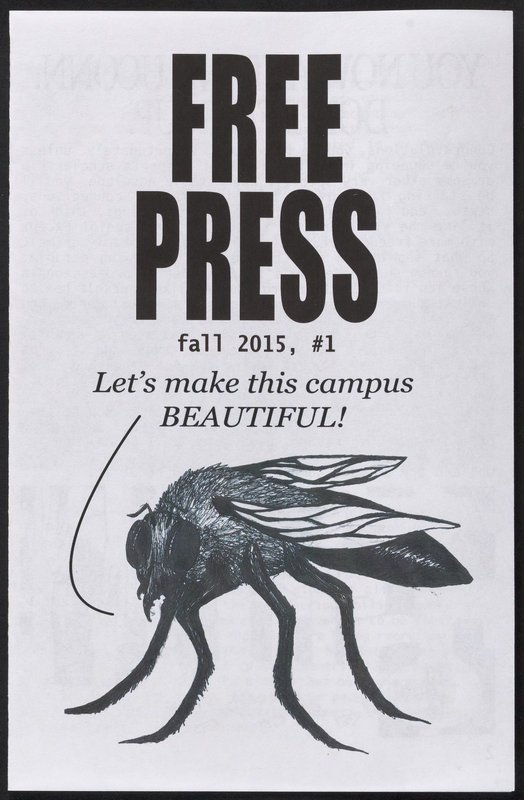

I was also tasked with reviewing several issues of UConn Free Press, another

independently produced zine, with more of an emphasis on poetry, artwork, and other

creative content than Ahimsa. This is not to say that articles on issues of social justice

were not present, quite the opposite. Free Press issues are chock full of articles, covering

topics of all kinds, from veganism to the legalization of MDMA to human sexuality.

While Free Press has a documented history stretching all the way back to the 1960s, the

issues I read were much more relatable to me, having been published in the 2010s.

As I reviewed these two pieces, I realized that while they were written in different

styles, covered different topics, and looked profoundly different, there was one key

element that ran throughout them: that of student engagement, of radicalism, and of

dissatisfaction with the state of the world. UConn’s student body has always been

passionate and committed to social progress, which is echoed in the same way today as

it was ten, thirty, and even fifty years ago. What made me want to write this article,

however, was what was happening today. Under the COVID-19 pandemic, activism

among students has been relegated to the digital world. Faced with overwhelming

hardship, both personally and worldwide, students have used the internet to have their

voices heard louder than ever. An excellent example of this is how over the summer,

dozens of Instagram accounts appeared addressing issues of racial disparity at the

University. While these efforts did not appear in print, like what I have reviewed over

the past few months, that same thread flowed through them; an intense desire for

change. Activists at UConn thrived and grew, as best they could, even while isolated.

However, this rise in online activism presents a unique problem for the archival

field. How do you archive work that only appears in an online space? It can change in

appearance at any point, depending on what device it is viewed on, whereas a book is

always a book. Do you take the item as it appears on a mobile device, or a desktop? Are

the comments archived? The likes? What happens if an archived page updates, and what

if the update is minor? This is not even to mention the problems of file obsolescence, the

cost of digital storage, and the problems with actually obtaining access to something like

a social media post, or a story that is gone within 24 hours. These digital items are just

as important as the printed ones, as they reflect an unflinching commitment to the

ideals of activism that have existed at UConn for decades. We have never had an

opportunity quite like this to not only record the piece itself, but those who interact with

it, or share it. We can record not just the end product, but the drafts and the sources in

one fell swoop. But without swift action, these ephemeral artifacts may be deleted,

corrupted, or otherwise removed from the public eye, and the online activism of UConn

students may be lost.