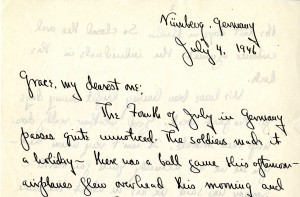

“The Fourth of July in Germany passes quite unnoticed. The soldiers made it a holiday — there was a ballgame this afternoon, airplanes flew overhead this morning and tonight Judge Parker is giving a party. but the court went on as usual.” p. 334 7/4/1946

Despite the completion of the direct defense and cross examination of the defendants, arguments continued to be presented regarding “the main juridical and fundamental problem of this Trial concerns war as a function forbidden by international law; the breach of peace as treason perpetrated upon the world constitution.” And so the morning session continued on as usual on the Fourth of July 1946.

THE PRESIDENT: The same observation applies to Dr. Exner’s letter of the 23d of June 1946 on behalf of the Defendant Jodl; only the Tribunal thinks that that letter also should be signed by the defendant, and read by Dr. Exner at 2 o’clock. I call on Dr. Jahrreiss.

PROFESSOR DR. HERMANN JAHRREISS (Counsel for Defendant Jodl): Mr. President and Gentlemen of the Tribunal, the main juridical and fundamental problem of this Trial concerns war as a function forbidden by international law; the breach of peace as treason perpetrated upon the world constitution. This problem dwarfs all other juridical questions. The four chief prosecutors have discussed the problem in their opening speeches, sometimes as the central theme of their presentation, sometimes as a fundamental matter, while indeed differing in their conceptions thereof. It is now up to the Defense to examine it. The body of Defense Counsel have asked me to conduct this examination. It is true that it is for each counsel to decide whether and to what extent he feels in a position to renounce, as a result of my arguments, his own presentation of the question of breach of the peace. However, I have reason to believe that counsel will avail themselves of this opportunity to such an extent that the intention of the Defense to contribute materially toward a technical simplification of the phase of the Trial which is now beginning, will be realized by my speech. I am concerned entirely with the juridical question, not with the appreciation of the evidence submitted during the past months. Also, I am dealing only with the problems of law as it is at present valid, not with the problem of such law as could or should be demanded in the name of ethics or of human progress. My task is purely one of research; research desires nothing but the truth, knowing full well that its goal can never be attained and that its path is therefore without end. I wish to thank the General Secretary of the Tribunal for having placed at my disposal documents of a decisive nature and very important literature. Without this chivalrous assistance it would not have been possible, under the conditions obtaining at present in Germany, to complete my work. The literature accessible to me originated predominantly in the United States. Familiar as I am with the vast French and English literature on this subject, which I have studied during the last quarter of a century-I am, unfortunately, not conversant with the Russian language-I believe, however, that I can fairly say that no important concept has been overlooked, because in no other country of the world has the disc cession of our problem, which has become the great problem of humanity, been more comprehensive and’ more profound than in the United States.

This very fact has enabled me to forego the use of legal literature published in the former German sphere of control. In this way even the semblance of a pro dome line of argumentation will be avoided. Owing to the short time at my disposal for the purpose of this speech, and at the same time in view of the abundance and complexity of the problems with which I have to deal, it will not be possible for me to cite all the documents and quotations I am referring to. I shall present only a few sentences. Any other procedure would interrupt the train of argument for the listener. I shall therefore submit to the Tribunal the documents and literary references In the form of appendices to my juridical arguments. What I am saying can thus quickly be verified.

The Charter threatens individuals with punishment for breaches of the peace between states. It would appear that the Tribunal is accepting the Charter as the unchallengeable foundation for all juridical considerations. This means that the Tribunal will not examine the question whether the Charter, as a whole or in parts, is open to juridical objections; yet such a question nevertheless continues to exist.

If this is so, why, then, have any discussion at all on the main fundamental legal problems?

The British chief prosecutor even made it the central theme of his long address to examine the relationship of the Charter, where our problem is concerned, to existing international law. He justified the necessity of his arguments by saying that it was the task of this Trial to serve humanity and that this task could be fulfilled by the Trial only if the Charter could hold its own before international law, that is, if punishment of individuals for breach of the peace between states was established in existing international law.

It is, indeed, necessary to clarify whether certain stipulations of the Charter may have created new laws, and consequently laws with retroactive force.

Such a clarification does not serve the purpose of facilitating the work of the historians. They will examine this, just as all the other findings in this Trial, according to the rules of free research; perhaps through many years of work and certainly without limiting the questions to be put and, if possible, on the basis of an ever greater wealth of documents and evidence.

Such a clarification is indispensable, if only for the reason that the decision as to right and wrong depends, or may depend, thereupon, all the more so if the Charter is considered legally unassailable.

Let us assume for the sake of argument that the Charter does not formulate criminal law which is already valid but creates new, and therefore retroactive, criminal law. What does this signify for the verdict? Must not this be of importance for the question of guilt?

Possibly the retroactive law which, for instance, penalizes aggressive war had not yet become fixed or even conceived in the conscience of humanity at the time when the act was committed. In that case the defendant cannot be guilty, either before himself or before others, in the sense that he was aware of the illegality of his behavior. Possibly, on the other hand, the retroactive law was promulgated at a time when a fresh conscience was just beginning to take shape, although not yet clear or universal. It is then quite possible for the defendant to be not guilty in the sense that he was aware of the wrongfulness of his commissions and omissions…..[http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/07-04-46.asp, accessed 6/27/2016]

–Owen Doremus and Betsy Pittman

[Owen Doremus, a junior at Edwin O. Smith High School, is supporting this blog series with research and writing as part of an independent study.]

The majority of the letters from Tom Dodd to his wife Grace have been published and can be found in Letters from Nuremberg, My father’s narrative of a quest for justice. Senator Christopher J. Dodd with Lary Bloom. New York: Crown Publishing, 2007.

Images available in Thomas J. Dodd Papers.