When a man is so destitute of a sense of morality and the fear of God, and, by the commission of enormous crimes, becomes such a dangerous member of society, as to render it necessary that he be taken off by the hand of justice, the feelings of the public are, in some degree, interested in his history (Welch 19).

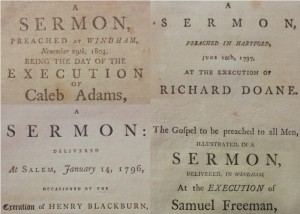

“In some degree?” Understatement of the year, Rev. Mr. Moses C. Welch, in your native 1805 or any other year. People were interested, whether it the was the case of Samuel Freeman, Caleb Adams, Richard Doane or Henry Blackburn—condemned and executed murderers all—and so the public sermons spoken at their deaths were printed into nice little salable pamphlets including extra features.

“In some degree?” Understatement of the year, Rev. Mr. Moses C. Welch, in your native 1805 or any other year. People were interested, whether it the was the case of Samuel Freeman, Caleb Adams, Richard Doane or Henry Blackburn—condemned and executed murderers all—and so the public sermons spoken at their deaths were printed into nice little salable pamphlets including extra features.

Consequently, from these pamphlets we can get a really clear image of what kind of event an execution was in eighteenth- and ninteenth-century New England: An important and well-attended public spectacle with “thousands of solemn and deeply affected spectators” (Waterman 31). In the pamphlet on Caleb Adams, we can see quite an elaborate event taking place around his death, with first a sermon by Elijah Waterman, followed directly by “Mr. Welch’s address, at the place of execution,” along with further acknowledgment that “a pathetic and well adapted prayer, by the Rev. Mr. Nott, opened the service” (Waterman 31), and that likewise at the end, “The Rev. Mr. Lyon addressed the Throne of Grace in language the most interesting and affectionate.—At the close of which, the criminal was launched into eternity” (Waterman 32).

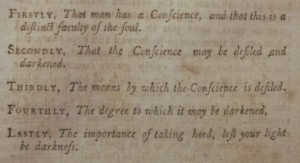

With four ministers in attendance, I think it’s safe to say that people were interested. And why shouldn’t they be, when the sermons (and executions) are more for them than the condemned? Across the board, these messages first aim to reach the congregation, with the sermon at Caleb Adams’ execution speaking specifically on the conscience,

FIRSTLY, That man has a conscience, and that this is a distinct faculty of the soul.

SECONDLY, That the Conscience may be defiled and darkened.

THIRDLY, The means by which the Conscience is defiled.

FOURTHLY, The degree to which it may be darkened,

LASTLY, The importance of taking heed, lest your light be darkness (Waterman 5).

As Caleb is one whose conscience is darkened, this message is about him, and not for him. Through use of the criminal as a counter-example, people may be made to see sin, and turn back; may be made to “look to yonder place of execution, around which we shall soon be gathered, to behold the most awful of sights. And. . . remember that this event is as a light which shineth, teaching us the present nature of sin, and the more awful judgments of God on such as live and die unreformed” (Strong 12).

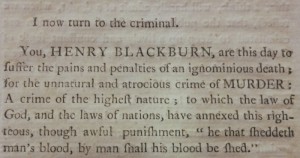

However, the condemned still must be addressed, and urged repentance in all sermons to all criminals. Thus, “to you, Caleb, I say, there is mercy with God—that he may be feared. Take heed that you exercise a heart-felt repentance toward God” (Waterman 17); and Richard, “if you have truly repented, the riches of divine grace in Jesus Christ and the sovereignty of divine love will be glorified in plucking you as a brand out of the burning” (Strong 13); and Samuel, “if you murdered Hannah Simons, and persist in denying it, however you may confess your other sins, you will die with a lie in your right hand” (Welch 16); and Henry, “if you have imposed on your sincerest friends, and deceived yourself, let me exhort you, in the most serious and pathetic manner, by the mercies of God, and by the affection which you bear to your own soul, to renounce your hypocrisy this instant” (Fisher 19).

Thus are the sermons themselves adapted to turning the congregation away from sin, and the condemned towards repentance. The sermon is a spiritual deterrent against crime as well as a corrective device for the criminal, really perfectly aligning it with the purposes of secular justice, as described by William White of Philadelphia in 1790, that “two reasons occur for taking away life. First, it is intended to hold forth an example of terror to others, and secondly, To prevent the same person from repeating a crime which he hath been found capable of committing” (White 4).

Yet while these New England Presbyterian Calvinists are busy reminding us that “[whoever] sheddeth man’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed” (Fisher 18, Welch, “Address” 19), they seem to have been somewhat behind on the times. White notes that “if these two ends can be attained by other means, policy and humanity will readily accede to the alternative” (White 4), advocating “substituting labor and confinement for corporal punishment and death” (White 4). He also prints a letter from Thomas Beevor in England, who writes that “many of those unhappy [executed] wretches, by regular, steady discipline in a penitentiary house, would have been rendered useful members of society (White 21). An Italian text, too, Essay on Crimes and Punishments (1785) states that “the death of a citizen cannot be necessary, but in one case. When, though deprived of his liberty, he has such power and connexions as may endanger the security of the nation” (Beccaria 103-104).

Yet while these New England Presbyterian Calvinists are busy reminding us that “[whoever] sheddeth man’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed” (Fisher 18, Welch, “Address” 19), they seem to have been somewhat behind on the times. White notes that “if these two ends can be attained by other means, policy and humanity will readily accede to the alternative” (White 4), advocating “substituting labor and confinement for corporal punishment and death” (White 4). He also prints a letter from Thomas Beevor in England, who writes that “many of those unhappy [executed] wretches, by regular, steady discipline in a penitentiary house, would have been rendered useful members of society (White 21). An Italian text, too, Essay on Crimes and Punishments (1785) states that “the death of a citizen cannot be necessary, but in one case. When, though deprived of his liberty, he has such power and connexions as may endanger the security of the nation” (Beccaria 103-104).

Even if New England was a bit behind on the times of the Enlightenment, though—in not making criminals “useful members of society”—these execution sermons themselves must have been a valuable part of the print market, since in their printed forms they regularly include many compelling features likely not found anywhere else. People wanted details, which the published sermons provide, often including “a short account of his life, as given by himself” (Strong 1). Here we may learn how in childhood, “[Caleb] was not properly governed” (Welch, “Address” 22), and even hear his own confession, that “after I determined to kill him, I never once thought of any thing, but how I should do it ; I did not think of the consequences to myself” (Waterman 28).

Therefore, execution sermons really accomplish much. From the openings directed at the spectators, to the direct address of the prisoner, and finally to the occasional appendices describing the life and crimes of the men executed, they serve as devices to religiously and morally reform society, taking one man’s ignominious death and using it as a doctrinal device, a device that can then be sold to the curious public. A bit crude, perhaps, but with thousands of spectators and a broad reading audience, likely effective. Society and the criminal are morally uplifted from the sermons preached on the criminal’s ill example, and, what’s more, someone was economically profiting through the sale of the sermons alongside details of the crime.

Therefore, execution sermons really accomplish much. From the openings directed at the spectators, to the direct address of the prisoner, and finally to the occasional appendices describing the life and crimes of the men executed, they serve as devices to religiously and morally reform society, taking one man’s ignominious death and using it as a doctrinal device, a device that can then be sold to the curious public. A bit crude, perhaps, but with thousands of spectators and a broad reading audience, likely effective. Society and the criminal are morally uplifted from the sermons preached on the criminal’s ill example, and, what’s more, someone was economically profiting through the sale of the sermons alongside details of the crime.

Good idea, since people were interested.

Daniel Allie is a senior undergraduate student in English. For his blog series Hypocrite Lecteur he will spend the Spring 2014 Semester exploring nineteenth-century literature in a variety of genres from the Rare Books Collection housed in Archives and Special Collections at the Dodd Research Center.

Works Cited

Beccaria, Cesare, marchese di. An Essay on Crimes and Punishments, translated from the Italian ; with a commentary attributed to Mons. De Voltaire translated from the French. London: E. Newbury, 1785. Print. [Dodd Center call number: B2404]

Fisher, Nathaniel. “A sermon: delivered at Salem, January 14, 1796, : occasioned by the execution of Henry Blackburn, on that day, for the murder of George Wilkinson.” Boston: John Dabney, 1796. Print. [Dodd Center call number: Gaines P-1191]

Strong, Nathan. “A sermon : preached in Hartford, June 10th, 1797, at the execution of Richard Doane.” Hartford: Elisha Babcock, 1797. Print. [Dodd Center call number: WBV 1]

Waterman, Elijah. “A sermon, preached at Windham, November 29th, 1803, being the day of the execution of Caleb Adams, for the murder of Oliver Woodworth.” Windham: John Byrne, 1803. Print. [Dodd Center call number: Gaines P-110]

Welch, Moses C. “The gospel to be preached to all men, illustrated, in a sermon, delivered, in Windham, at the execution of Samuel Freeman.” Windham: John Byrne, 1805. Print. [Dodd Center call number: Gaines P-1195]

Welch, Moses C. “Mr. Welch’s Address, at the Place of Execution.” Windham: John Byrne, 1803. Print.[Dodd Center call number: Gaines P-110 (same volume as Waterman’s sermon)]

White, William [ed.] “Extracts and remarks on the subject of punishment and reformation of criminals.” Philadelphia: Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons, 1790. Print. [Dodd Center call number: Gaines P-1612]