“He who was born to be hanged would never be drowned” (Tufts 118).

“He who was born to be hanged would never be drowned” (Tufts 118).

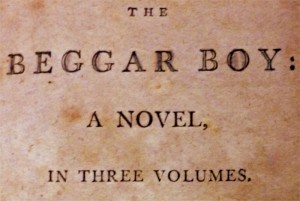

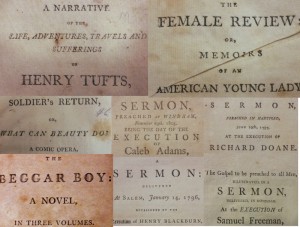

Born to be Hanged. The summation of a damnable life, and thus the best possible prospective title for a book which is instead entitled A Narrative of the Life, Adventures, Travels and Sufferings of Henry Tufts, Now Residing at Lemington, in the District of Maine, In substance, as compiled from his own mouth (1807).

But why Born to be Hanged? Well you see, in his own time, “the name of HENRY TUFTS, the author and hero of the following narrative, [has] been famous, or rather infamous, through most of the United States” (Tufts 3). He was a criminal who eventually retired from crime and prison (by escaping) and wrote this delightful book about it all: within, read of how he and an accomplice were jailed and attempted to “burn a passage through the side of the jail, and so make our escape” (39), accidentally burning down the jail instead; how he “had learnt to disguise a horse so artificially. . . that the owner, to have known his property again, must have had uncommon sagacity” (115); how he traveled, “appearing sometimes in the character of a physician, and sometimes as priest, as best suited my purposes” (114); and how he once stole a horse by “personat[ing] him whom I had long served, vis. the Devil” (229).

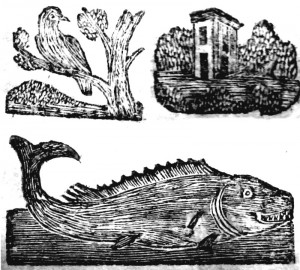

Each chapter ends with a small engraving, ranging from the bucolic to the bizarre and horrid. Here are a few samples.

And much, much more! Let me not neglect to mention also that all of this happened during the Revolutionary War: after “the horrors of a civil war had burst forth between England and her colonies in America” (Tufts 101), even Henry takes up soldiering, though enlisting merely seems to him “the best method of supporting self and family, in a way consistent with my beloved ease, and at the same time, as, certainly more honorable than thievish pursuits, though a soldier in fact, may be a thief” (Tufts 101).

Seeing the Revolutionary War from the eyes of one who cared not one jot about it is really a remarkable thing. As noted by his first reviewer, Thomas Wentworth Higginson (some fifty years after Henry’s death), “the lives of vagabonds often afford the very best historical materials” (Higginson 605), and so “in him we have the reverse side of the Revolutionary soldier; he shows vividly the worst part of the material out of which Washington had to make an army” (Higginson 608).

Indeed, what bad material! Henry remains a thief, stealing one night “a couple of dunghill fouls” (Tufts 103), and “a couple of geese more” (Tufts 103) from a local farmer. Perhaps worse, too, dear Henry was not even reliably in the army. He enlisted numerous times, once “under Capt. True for three years” (Tufts 131), but “growing sick, at the thoughts of a three years’ campaign, and having now a convenient opportunity for desertion, I made use of the privilege” (Tufts 132). Additionally, he even engages in undermining the American economy: he meets a British agent, a counterfeiter, who tells him “that, as congress had issued a paper medium to raise armies, and pay off their troops, it imported their adversaries to discredit the currency as effectually as possible” (Tufts 178). He then readily accepts one thousand dollars in counterfeits, finding “not the slightest difficulty in passing them” (Tufts 179).

Thus our clever hero shows us the underside of the American Revolution, yet how much can we really trust a thief, no matter how much he tells us that “I have worn no  marks, no disguises, but have appeared in my every day dress” (Tufts 364)? We cannot. Conducting further research, I found only George Wadleigh in 1913 citing an incident of August 26, 1794, in which “Theophilus Dame, Sheriff [of Dover, N.H.], gives notice that ‘the noted Henry Tufts broke out of goal on the night of the 25th.’ He was ‘confined for his old offence, that is, teft,” (sic) and is described as ‘about six feet high, and forty years of age, wears his own hair, short and dark coloured, had on a long blue coat’” (Wadleigh 185).

marks, no disguises, but have appeared in my every day dress” (Tufts 364)? We cannot. Conducting further research, I found only George Wadleigh in 1913 citing an incident of August 26, 1794, in which “Theophilus Dame, Sheriff [of Dover, N.H.], gives notice that ‘the noted Henry Tufts broke out of goal on the night of the 25th.’ He was ‘confined for his old offence, that is, teft,” (sic) and is described as ‘about six feet high, and forty years of age, wears his own hair, short and dark coloured, had on a long blue coat’” (Wadleigh 185).

Such confirmation of Tufts’ prison-breaking is helpful, though this is a lone source, as the only two other accounts I found were completely anecdotal, and possibly based on Tufts’ book alone. Charles Henry Bell writing in 1888 notes that “the jail in Exeter, during the Revolution. . . was not a very safe place of confinement, as was proved by the notorious Henry Tufts and others having made their escape from it” (Bell 256), while, finally, Mary Pickering Thompson writes in 1892 that “the Tufts family. . . has acquired an unenviable notoriety from the exploits of Henry Tufts” (Thompson 257).

Thus, we have very little to confirm Tufts’ actual adventures, so what can we take away? Henry Tufts himself believed his book to be moral, for “the history of the wise and benevolent is beneficial to society. . . [while] that of the vicious, affords also, instruction, shewing the effects of vice and immorality” (Tufts 7). He intends to show his harmful acts truthfully, ab ovo usque ad mala—from beginning to end (Ovid, qtd. Tufts title page)—to inspire moral behavior.

This moral purpose is reinforced by other works published by Tufts’ publisher, Samuel Bragg of Dover. Bragg published the Dover newspaper The Sun, promising “Here Truth unlicensed Reigns” (Nelson 62), and, here in the archives, printed an “Oration, delivered on the fourth of July 1796” by the Rev. Simon Finley Williams, who (ironically, due to Henry) says how in the Revolution, “Heaven seemed to unite all Americans into one soul, except some fugitive Cains” (Williams 9). The ilk of Henry aside, though, these works uplift society, holding up the nation and the law itself, as also in Bragg’s publication of the New Hampshire constitution in 1805, or, even better, The Complete  Justice of the Peace, by Moses Hodgdon (1806), which states that “Governments may be predicated and enacted with an intention to cherish and support them ; but unless the magistrates, whose duty it is to execute the laws, feel an attachment to the first principles of their government. . . the laws themselves soon become a dead letter” (Hodgdon, Dedication, n.pag.).

Justice of the Peace, by Moses Hodgdon (1806), which states that “Governments may be predicated and enacted with an intention to cherish and support them ; but unless the magistrates, whose duty it is to execute the laws, feel an attachment to the first principles of their government. . . the laws themselves soon become a dead letter” (Hodgdon, Dedication, n.pag.).

Why then do we have Henry Tufts? Because of faulty magistrates, of course! But I jest. Bragg is involved in society and the law, and so also publishes the autobiography of a criminal, intending to improve society. Yet are we better for it? I delighted in Henry’s crimes. Moral indignation was far from my mind. How could one not be amused by his stealing a horse through drugging its guards, while pretending to be hunting for Henry Tufts, all while actually operating on a bet with the owner? How is burning down the jail, and so needing to stay with the warden’s family, with “thanksgiving being near” (Tufts 42) not amusing? Moreover, though we cannot confirm his adventures, how is a book written by someone in the era of the Revolutionary war not historically significant?

It’s at once historical and ahistorical; moral and amoral; honest and false; and I love it. Perhaps this joy ultimately shows us that we are all somehow like Henry Tufts, for Meliora video, proboque, detiriore sequor (Ovid, qtd. Tufts title page): I see the better, and I approve, but I follow worse.

As a reader, I sure followed Henry Tufts.

Daniel Allie is a senior undergraduate student in English. For his blog series Hypocrite Lecteur he will spend the Spring 2014 Semester exploring nineteenth-century literature in a variety of genres from the Rare Books Collection housed in Archives and Special Collections at the Dodd Research Center.

Works Cited

Bell, Charles Henry. History of the Town of Exeter, New Hampshire. Boston: J. E. Farwell & Company, 1888. Web. Google Books. 1 March 2014.

Constitution and laws of the State of New-Hampshire : together with the Constitution of the United States. Published by authority. Dover: Samuel Bragg, jun. for the State, 1805. Print. [Dodd Center call number: Gaines 865].

Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. “A New England Vagabond.” Harper’s Magazine 76 (1888) 605-611. Web. Google Books. 1 March 2014.

Hodgdon, Moses. The complete justice of the peace. Dover: Charles Peirce and S. Bragg, jr, etc., 1806. Print. [Dodd Center call number: B3029].

Nelson, William (ed.). Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New Jersey, vol. XIX. Paterson: The Press Printing and Publishing Co., 1897. Web. Google Books. 4 March 2014.

Thompson, Mary Pickering. Landmarks in Ancient Dover, New Hampshire. Concord: Concord Republican Press Association, 1892. Web. Google Books. 1 March 2014.

Tufts, Henry. A Narrative of the Life, Adventures, Travels and Sufferings of Henry Tufts, Now Residing at Lemington, in the District of Maine In substance, as compiled from his own mouth. Dover: Samuel Bragg, 1807. Print. [Dodd Center call number: A1838]

Wadleigh, George. Notable Events in the History of Dover, New Hampshire: From the First Settlement in 1623 to 1865. Tufts College Press, 1913. Web. Google Books. 1 March 2014.

Williams, Rev. Simon Finley. “An oration, delivered on the fourth of July 1796. Being the anniversary of the American independence at Meredith bridge.” Dover: Samuel Bragg, 1796. Print. [Dodd Center call number: Gaines P-929]

See Also: Tufts, Tom. “Henry Tufts, Black Sheep of an Otherwise Respectable Family.” Heather Wilkinson Rojo, Nutfield Genealogy. Web. 14 September 2012. Accessed 1 March 2014. [link: http://nutfieldgenealogy.blogspot.com/2012/09/henry-tufts-black-sheep-of-otherwise.html]

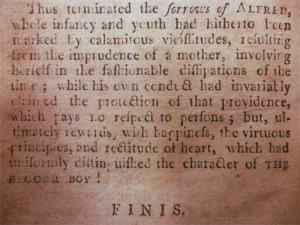

A fine way to end things. Here as I end this series I’m glad to report that I likely have a better claim on the truth of these words than Henry Tufts did, yet this isn’t enough for an end. I have now traversed the darksome valleys of the novel, autobiography, comedy, biography, oratory, and sermons, roughly between the years 1790 and 1810, and if there’s one thing I’ve learned from these texts, it’s that everything needs a moral. I need to leave you with something you may not have heard before but which is clearly exemplified through what I have been saying all along.

A fine way to end things. Here as I end this series I’m glad to report that I likely have a better claim on the truth of these words than Henry Tufts did, yet this isn’t enough for an end. I have now traversed the darksome valleys of the novel, autobiography, comedy, biography, oratory, and sermons, roughly between the years 1790 and 1810, and if there’s one thing I’ve learned from these texts, it’s that everything needs a moral. I need to leave you with something you may not have heard before but which is clearly exemplified through what I have been saying all along.