We welcome intern Giorgina Paiella, an undergraduate student majoring in English and minoring in philosophy and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies. In her new blog series, “Man, Woman, Machine: Gender, Automation, and Created Beings,” she will explore treatments of created and automated beings in archival materials from Archives and Special Collections.

We love stories of animation. Over the centuries, humanity has certainly not tired of works that engage with creation, artificiality, and the relationship between animator and animated. It’s in our myths, our movies, our television shows, and our literature—from children’s narratives to infamous novels. As a writing intern in Archives and Special Collections at the Dodd Research Center this semester, I plan to examine technology magazines, the children’s literature collection, alternative press  publications, and other archival materials that explore the rise of automation and various iterations of automata and reflect upon how these representations can inform inquiries about gender, humanity, personhood, and our increasingly intimate relationship with technology.

publications, and other archival materials that explore the rise of automation and various iterations of automata and reflect upon how these representations can inform inquiries about gender, humanity, personhood, and our increasingly intimate relationship with technology.

For my first post in this blog series, I’m going to explore the trend of incorporating issues of gender into a discussion of scientific discoveries, which I have identified in several early technology publications. I read the second issue of the science and science fiction magazine Omni, a publication that founder Kathy Keeton created in 1978 with the intention of exploring “all realms of science and the paranormal, that delved into all corners of the unknown and projected some of those discoveries into fiction.” As I searched for themes that would be relevant to my research objectives, I was fascinated by the frequency at which language relating to second-wave feminism contributes to the dialogue about scientific and technological discoveries.

This is not entirely surprising, especially considering that the issue was published in November 1978, an era of burgeoning feminist activity. Some of these references were more explicitly linked to women’s issues than others. One article describes the computer revolution as “computer lib,” a clear nod to the women’s liberation movement, commonly referred to as “women’s lib.” A short news headline details the development of a birth control pill for dogs, so “fido can have sex without fear.” The description that follows reads like a parody of the female birth control pill introduced in the 1960s: “this planned parenthood for pups is dispensed by veterinarians for about five cents a day and is claimed to be 90 percent effective in stopping estrus (heat) in bitches of all sizes and descriptions.”

Another article within this issue of Omni discusses papers and novels that speculate on the scientific and cultural possibilities of a longevity pill, including Jib Fowles’s “The Impending Society of Immorals” and Albert Rosenfeld’s Prolongevity, which cites over 500 scientific papers in its bibliography. The article also describes an assignment given to thirty-one students at the University of Houston in the department of future studies to predict how a longevity pill would alter society. Their collective prediction utilizes the same alarmist dystopian rhetoric adopted by opponents of the birth control pill:

One year after the introduction of the antiaging pill, traditional religions warn against death control a campaign similar to the earlier crusade against birth control; the economy is destabilizing as employees desert their jobs; government has moved in to monopolize distribution of the pill; and the divorce rate is increasing. Ten years later, organized religion is disgraced and disbanded, virtually everyone is taking the pill, divorce rates soar, the economy is staggering because of an increase in absenteeism, and all dangerous sports are phasing out as people everywhere reorient themselves to the quest for physical immortality.

The concept of life extension is, in fact, a centuries-old trope, but this article demonstrates the way in which existing gender debates became interwoven into discussions about technological advances. Continuing on the topic of longevity technology, the author explains that “until now it was necessary for post-menopausal humans to die and get their bodies off the scene to make room for the new arrivals.”  Of course, we’re not simply talking about post-menopausal humans, but rather post-menopausal women. The objectification of women’s bodies is also far from a new phenomenon, but notice the language: they must “die and get their bodies off the scene” to make way for “new arrivals.”

Of course, we’re not simply talking about post-menopausal humans, but rather post-menopausal women. The objectification of women’s bodies is also far from a new phenomenon, but notice the language: they must “die and get their bodies off the scene” to make way for “new arrivals.”

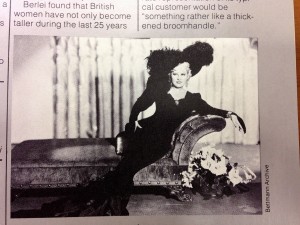

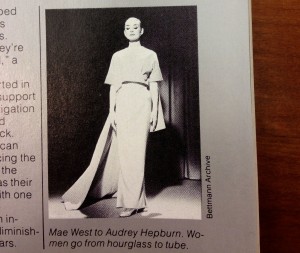

The rise of mechanization and speculations on new technological possibilities amplified ideas regarding the mind/body dualism and the disposability of bodies—particularly female bodies. Another article, “The Changing Shape of Women,” recounts findings from a study conducted by Berlei, the leading manufacturer of women’s undergarments in England at the time. The company describes changing trends in female body measurements, with a sample of over 4000 British and American women revealing taller frames on average, smaller breasts and hips, and thicker waists, more generally described as a “straightening of their curves.” Berlei cites poor eating habits and hormonal abnormalities from food additives as potential  explanations, but whatever the cause, “the traditional hourglass shape is no longer symbolic of today’s women.” When tasked with describing their average customer, the company states, “something rather like a thick-ended broomhandle…one might even say they’re becoming man-shaped.”

explanations, but whatever the cause, “the traditional hourglass shape is no longer symbolic of today’s women.” When tasked with describing their average customer, the company states, “something rather like a thick-ended broomhandle…one might even say they’re becoming man-shaped.”

So what does this have to do with created beings like automata, cyborgs, and robots? Existing cultural views often inform the characteristics and treatment of these beings, and attitudes toward embodied human females can therefore provide insights into female technological portrayals, and vice versa. For example, a female automaton can reveal something that would perhaps not be readily apparent about the expected appearance, behavior, and roles of human women. Similarly, the body of a female cyborg can call attention to attitudes regarding female bodies and their biological processes. I aim to keep these blurred boundaries between man and machine—or perhaps more accurately, woman and machine—in mind as I continue to work through the archives.

– Giorgina Paiella