The issue of sexism in video games may seem like a modern one, especially in light of events like the recent GamerGate controversy. Although discussions about violence and sexism in video games are still extraordinarily relevant in the present day, they actually have a history dating back to 1980s digital culture. In the early 1980s, when video game production was on the rise, these discussions introduced new ethical questions about technological representations.

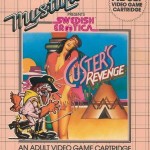

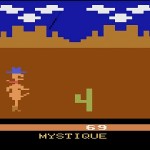

I recently looked through feminist alternative press publications like Off Our Backs and New Women’s Times. These periodicals discuss the 1982 release of a video game called Custer’s Revenge, designed for the Atari 2600 video game console by American Multiple Industries (AMI). The goal of the game is to maneuver a naked and erect General Custer across the desert, arrows flying, toward a red-skinned, dark-haired Native American woman tied to a cactus. After he reaches the woman, he rapes her as his revenge and reward—as the tagline of the game notes, “you score, when you score.” In the 1980s, video game producers like Playaround and AMI started to churn out many x-rated video games, including “Beat ‘em and Eat ‘em,” “Harem,” and “Bachelor Party.” The latter game features eight naked women and one man, where the object of the game is to maneuver the man to each of the eight women, scoring a point after each “victory” and causing the female figure to physically disappear from the screen after the conquest. These games were produced in response to a growing demand for pornographic games, which were expected to gross more than $1 billion annually on the adult market. Although sale of the game was restricted to minors, this did not preclude younger gamers from being exposed to it. Atari even filed a lawsuit against AMI because of the negative attention and association drawn between the system and Custer’s Revenge.

I recently looked through feminist alternative press publications like Off Our Backs and New Women’s Times. These periodicals discuss the 1982 release of a video game called Custer’s Revenge, designed for the Atari 2600 video game console by American Multiple Industries (AMI). The goal of the game is to maneuver a naked and erect General Custer across the desert, arrows flying, toward a red-skinned, dark-haired Native American woman tied to a cactus. After he reaches the woman, he rapes her as his revenge and reward—as the tagline of the game notes, “you score, when you score.” In the 1980s, video game producers like Playaround and AMI started to churn out many x-rated video games, including “Beat ‘em and Eat ‘em,” “Harem,” and “Bachelor Party.” The latter game features eight naked women and one man, where the object of the game is to maneuver the man to each of the eight women, scoring a point after each “victory” and causing the female figure to physically disappear from the screen after the conquest. These games were produced in response to a growing demand for pornographic games, which were expected to gross more than $1 billion annually on the adult market. Although sale of the game was restricted to minors, this did not preclude younger gamers from being exposed to it. Atari even filed a lawsuit against AMI because of the negative attention and association drawn between the system and Custer’s Revenge.

The first game of its kind to be released, Custer’s Revenge received significant attention in the press. Moreover, the game’s fusion of sexist and racist content created uproar in the activist community. Members of organizations like the New York Chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW), Women Against Pornography (WAP), and the American Indian Community House (AICH) organized an October 1983 protest against the inclusion of racism, sexual exploitation, pornography, and profiteering in video games with the hope of pulling pornographic games from store shelves. Denise Fuge, then-president of NY NOW, reflected upon how sexist video games push teenage boys closer to our culture’s acceptance of recreational violence against women. In response, representatives from AMI stated that the game is simply harmless fun depicting “an act of two consenting adults” and therefore could not be construed as enacting violence on women.

Custer’s Revenge was ultimately pulled from the market. The release of inappropriate video games presented new ethical questions about technological representations, the most important of which I will refer to as “moral slippage.” Both in the era of these early pornographic games and in the current day, many debates focus on the extent to which fictional representations like video games can influence real-life behavior. Copycat behavior and replication of violent acts that are depicted in films, music, and games are not uncommon in violent crimes—after all, there is no value-free pop culture. This is not to say that all individuals who play violent games are themselves violent or sexist, but young populations in particular are vulnerable to accepting and adopting problematic views. Custer’s Revenge, for example, was not simply a game or harmless fun, but rather promoted rape culture and racism.

Custer’s Revenge was ultimately pulled from the market. The release of inappropriate video games presented new ethical questions about technological representations, the most important of which I will refer to as “moral slippage.” Both in the era of these early pornographic games and in the current day, many debates focus on the extent to which fictional representations like video games can influence real-life behavior. Copycat behavior and replication of violent acts that are depicted in films, music, and games are not uncommon in violent crimes—after all, there is no value-free pop culture. This is not to say that all individuals who play violent games are themselves violent or sexist, but young populations in particular are vulnerable to accepting and adopting problematic views. Custer’s Revenge, for example, was not simply a game or harmless fun, but rather promoted rape culture and racism.

Although modern games are not as overt as Custer’s Revenge, they still incorporate troubling sexual content and depictions of violence. Despite its incredibly loaded content, the pixelated simplicity of Custer’s Revenge allowed many to brush it off as harmless in its time. Simulation and interactivity have always been integral aspects of gaming. Technology has greatly advanced since the days of early gaming, however, resulting in modern games that contain more graphic and realistic content. This heightened realism intensifies the debate about sexist and violent video games in the modern day because it further blurs the boundary separating gamer, game interface, and reality.

Intern Giorgina Paiella is an undergraduate student majoring in English and minoring in philosophy and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies. In her new blog series, “Man, Woman, Machine: Gender, Automation, and Created Beings,” she explores treatments of created and automated beings in historical texts and archival materials from Archives and Special Collections.