I cannot desire you to adopt the example of our Heroine, should the like occasion offer ; yet, we must do her justice. (Mann 116)

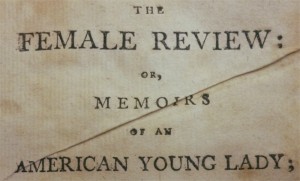

Thus speaks Herman Mann, the author of The Female Review: or, Memoirs of an American Young Lady (1797), whose opinions in addition to his doubly-masculine name indicate his deep disapproval of his subject, Deborah Sampson Gannett,  an unusual woman “whose life and character are peculiarly distinguished—Being a continental soldier for nearly three years in the late American war” (Mann 1).

an unusual woman “whose life and character are peculiarly distinguished—Being a continental soldier for nearly three years in the late American war” (Mann 1).

That’s right, folks—here, after looking at the indomitable Henry Tufts, we have yet another unlikely veteran of the American Revolution, this time a woman, who, finding herself too constrained by society, “determined to burst the bands, which, it must be confessed, have too often held her sex in awe” (Mann 110), and “join[ed] the American Army in the character of a voluntary soldier” (114), “enrolled by the name of ROBERT SHURTLIEFF” (Mann 129).

Sound fascinating? Certainly. Brave? Undoubtedly. Improper? Ask Mann. Mann must ask the question of what to do with this woman war hero, as it is his self-appointed task to tell of Gannett’s actions, but his disapproval is apparent everywhere, beginning with a disclaimer that he writes “not with intentions to encourage the like paradigm of FEMALE ENTERPRISE—but because such a thing, in the course of nature, has occurred” (Mann iii). Get the picture? Don’t anybody get any ideas. You’re only hearing this story because it’s true. It happened, and Gannett did fine, and served her country with honor, but Mann doesn’t want to risk indicating approval.

Mann does, however, intend to influence the conduct of American women, with his text becoming by intention one of instruction. He begins by saying “there are but two degrees in the characters of mankind, that seem to arrest the attention of the public. The first is that of him, which is the most distinguished in laudable and virtuous achievements. . . The second, that of him, who has arrived to the greatest pitch of vice and wickedness” (Mann v), and that “whilst the former ever demands our love and imitation, the other should serve to fortify our minds against its own attacks.” Stories of virtue and stories of vice can all lead you to virtue. Mann doesn’t say which he thinks this story is, though, and when we consider that Henry Tufts speaks in the same way of his criminal autobiography, “that [the life] of the vicious, affords, also, instruction, by showing effects of vice and immorality” (Tufts vii), regard doesn’t seem too high for Gannett in The Female Review.

However, it seems that others were not so reluctant in praising her. She made headlines for several years, for, as reported in 1797,“she had served as a soldier in the American army, during the war, had been wounded in the service, and therefore prayed a pension, as being unable any longer to support herself” (“The Time Piece” 3). This had already caught the attention of the press even as early as 1792, with an article saying in March that “from the feelings which appeared on the occasion, expressive to reward heroism like hers, there is no room to doubt that a compensation will be granted, adequate to her services, and honourable to the government” (“Female Heroism” 110).

The press seems proud of Gannett, taking her accomplishment as an act of patriotic heroism, and the best further evidence for this appears in The Time Piece and Literary Companion of December 4, 1797 in the form of a poem, “On Deborah Gannett,” which identifies her as “the American heroine,” while praising Gannett as “HER, who never war did fear,” asking us to

Reflect—how many tender ties

A woman must forego

Ere to the field of war she flies,

To meet a savage foe—

How many bars has nature plac’d,

And custom many more

That women never should be grac’d

With honors won from war.

All these she nobly overcame. . . (“On Deborah Gannett” 2)

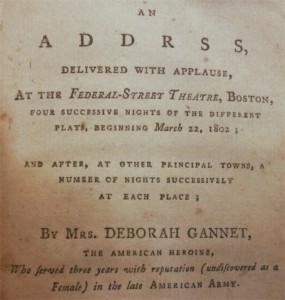

Gannett overcame, at least when it came to the prejudice of the press. This woman war hero was a paragon of virtue. However, public opinion notwithstanding, Gannett apparently still needed to seek some means of support, and still needed to reconcile herself with her actions, delivering a speech in Boston, March 1802,  which was then printed and bound in our volume of The Female Review. Here we finally see her as she saw herself, and she abruptly shows herself to be a harsher critic of herself than Mann, saying of her experience “I recollect it with a kind of satisfaction, which no one can better conceive and enjoy than him, who, recollecting the good intentions of a bad deed, lives to see and to correct any indecorum of his life” (Gannett 7).

which was then printed and bound in our volume of The Female Review. Here we finally see her as she saw herself, and she abruptly shows herself to be a harsher critic of herself than Mann, saying of her experience “I recollect it with a kind of satisfaction, which no one can better conceive and enjoy than him, who, recollecting the good intentions of a bad deed, lives to see and to correct any indecorum of his life” (Gannett 7).

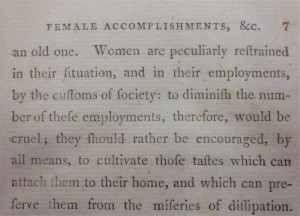

Her military service now a “bad deed,” Gannet says “I therefore yield every claim of honor and distinction to the hero and patriot, who met the foe in his own name” (Gannett 23), finally falling back on conservative, rather British orthodoxy, stating that “the field and the cabinet are the proper spheres assigned for our MASTERS and our LORDS ; may we, also, deserve the dignified title and encomium of MISTRESS and LADY, in our kitchens and in our parlours” (Gannett 28-29), sounding just as British as an 1801 British text on education, which states that young women “should rather be encouraged, by all means, to cultivate those tastes which can attach  them to their home, and which can preserve them from the miseries of dissipation” (Edgeworth 7).

them to their home, and which can preserve them from the miseries of dissipation” (Edgeworth 7).

What then can we do with Deborah Gannett? We cannot entirely praise her as a hero against her society, nor as a perfectly liberated American revolutionary—because of her own vehement repudiation of her own self-liberating actions—and nor could her contemporaries—herself included—praise her as a model of virtue, any more than they could praise the like of Henry Tufts, because of the very actions which we find praiseworthy. Perhaps we cannot take away “virtue” from Gannett any more than others could in her own time; perhaps it would be naive to take this as an indication of “how far we’ve come;” but perhaps what is most important is that we can see a widespread debate over Gannett and gender playing out within these contemporary texts: texts fascinated with Gannett and her accomplishments, texts taking up the story because of its patriotic value; texts thus wanting to praise Gannett at times, but texts in a society that could not accept her, tragically leading to her rejection of herself.

Better than a hero, and more than a moral counterweight, then, Gannett is historical. Leaving moral considerations and questions of virtue or vice or heroism behind, let us regard her as such.

Daniel Allie is a senior undergraduate student in English. For his blog

series Hypocrite Lecteur he will spend the Spring 2014 Semester exploring nineteenth-century literature in a variety of genres

from the Rare Books Collection housed in Archives and Special Collections at the

Dodd Research Center.

Works Cited

Edgeworth, Maria and R.L. Practical Education: Volume 3. London: J. Johnson, 1801. Print. [Dodd Center call number: B3726]

“Female Heroism.” The New York Magazine, or Literary Repository 3.4 (April 1792): 110. American Periodicals. Web. 04 April 2014.

Gannett, Deborah Sampson. “An address, delivered with applause, at the Federal-Street Theatre, Boston, four successive nights.” Dedham: Herman Mann, 1802. Print. [Dodd Center call number: A571 (same volume as Female Review)]

Mann, Herman. The Female Review: or, Memoirs of an American young lady. Dedham: Nathaniel and Benjamin Heaton, 1797. Print. [Dodd Center call number: A571]

“On Deborah Gannett.” The Time Piece, and Literary Companion, 2.35 (December 4, 1797): 2. American Periodicals. Web. 04 April 2014.

“The Time Piece.” The Time Piece, and Literary Companion 2.34 (December 1, 1797): 3. American Periodicals. Web. 04 April 2014.

Tufts, Henry. A narrative of the life, adventures, travels and sufferings of Henry Tufts. Dover: Samuel Bragg, 1807. Print. [Dodd Center call number: A1838]