Daniel Allie is a senior undergraduate student in English. This is the final post in his series Hypocrite Lecteur …

I have kept nothing back, nor ought have I extenuated ; neither have I dealt in ornamental flourishes, for to the graces of refined composition I have little title, or indeed ambition, to lay claim. Plain truth I adopted as a polar star, which I intend to pursue invariably without compelling the reader to dance over the fairy land of metaphor, or grope through the darksome vallies of allegory (Tufts 364).

A fine way to end things. Here as I end this series I’m glad to report that I likely have a better claim on the truth of these words than Henry Tufts did, yet this isn’t enough for an end. I have now traversed the darksome valleys of the novel, autobiography, comedy, biography, oratory, and sermons, roughly between the years 1790 and 1810, and if there’s one thing I’ve learned from these texts, it’s that everything needs a moral. I need to leave you with something you may not have heard before but which is clearly exemplified through what I have been saying all along.

A fine way to end things. Here as I end this series I’m glad to report that I likely have a better claim on the truth of these words than Henry Tufts did, yet this isn’t enough for an end. I have now traversed the darksome valleys of the novel, autobiography, comedy, biography, oratory, and sermons, roughly between the years 1790 and 1810, and if there’s one thing I’ve learned from these texts, it’s that everything needs a moral. I need to leave you with something you may not have heard before but which is clearly exemplified through what I have been saying all along.

So here’s a moral for you: this literature is important. This literature is worth reading. This literature is good. It can be everything literature today is; it’s funny, sad, and surprising; it can entertain us as much as it can teach us. These texts are preserved in the archives, and they deserve to be there.

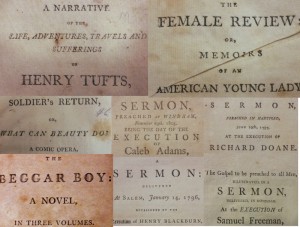

When we read Thomas Bellamy’s The Beggar Boy, we get a strangely frenetic and entertaining story, and see early nineteenth-century state of the novel; In Henry Tufts, we get the most ridiculously entertaining narrative I’ve ever read, along with the historical context to make it objectively important, the same way that Deborah Gannett’s life and The Female Review were important, regardless of how unfortunate her own self-repudiation was; In Theodore Hook’s The Soldier’s Return, we see an amusing glimpse of comedy, and the regard towards theater in the United States; and in the execution sermons, the application of capital punishment in the moral and economic life of society.

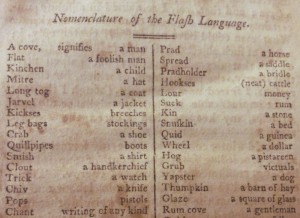

Yet make no mistake. I could have said more. I could have told you about Bellamy’s  illustrations of the vast British Empire, that a convict is shipped off to “Botamy-Bay” (Bellamy 210-211), and the fact that Alfred is forced to go to Jamaica; of Henry Tufts I could have pointed to so much more, that he “[visits] the Indians of Sudbury, Canada” (Tufts 65) and describes their ways in detail; and how, while in prison he gives a detailed account of “the flash lingo,” “[which]. . . is partly English and partly an arbitrary gibberish, which, when spoken, presents to such hearers, as are not initiated into its mysteries, a mere unintelligible jargon” (Tufts 315), where “going to the nipping jig to be topt” (Tufts 317) means to be hanged, to “undub the qua” (316) is “unlock the jail,” and in which a “yapster” is a dog (316).

illustrations of the vast British Empire, that a convict is shipped off to “Botamy-Bay” (Bellamy 210-211), and the fact that Alfred is forced to go to Jamaica; of Henry Tufts I could have pointed to so much more, that he “[visits] the Indians of Sudbury, Canada” (Tufts 65) and describes their ways in detail; and how, while in prison he gives a detailed account of “the flash lingo,” “[which]. . . is partly English and partly an arbitrary gibberish, which, when spoken, presents to such hearers, as are not initiated into its mysteries, a mere unintelligible jargon” (Tufts 315), where “going to the nipping jig to be topt” (Tufts 317) means to be hanged, to “undub the qua” (316) is “unlock the jail,” and in which a “yapster” is a dog (316).

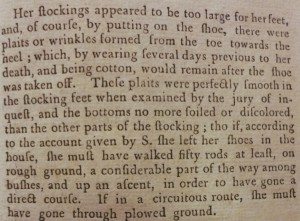

Or in The Soldier’s Return, I could have looked at the imperial assumptions likely behind the use of an Irishman, Dermot O’Doddipole, as the comic relief; I could have  said how Herman Mann avoids writing about Deborah Gannett by digressing about extraterrestrial life, that “the probability is, that millions, yea, on infinite number of such bodies [stars] are peopled by inhabitants not dissimilar to our own” (Mann 48); or in the execution sermons I could have told you about the men’s crimes, and the murder investigations, discussed in detail in the pamphlet on Samuel Freeman; or looked at rhetorical technique, how these several ministers present the same type of message based upon wildly different scriptures, with Nathan Strong using Hosea 5:6, while Nathaniel Fisher uses Second Corinthians 5:10.

said how Herman Mann avoids writing about Deborah Gannett by digressing about extraterrestrial life, that “the probability is, that millions, yea, on infinite number of such bodies [stars] are peopled by inhabitants not dissimilar to our own” (Mann 48); or in the execution sermons I could have told you about the men’s crimes, and the murder investigations, discussed in detail in the pamphlet on Samuel Freeman; or looked at rhetorical technique, how these several ministers present the same type of message based upon wildly different scriptures, with Nathan Strong using Hosea 5:6, while Nathaniel Fisher uses Second Corinthians 5:10.

So if you’re not already convinced: this literature is rich in literary and historical value, and even entertainment value. It all bears the mark of its own time and has its own  qualities that make it worthwhile. I began with the express desire of working against the academic textbook anthology by going to complete texts myself, and so I have done. As varied as it is, going from pious the novel, sermons, biography, to frivolous comedy to amoral autobiography, I’ve formed my own anthology, my own set of important literature: I have found these works, and introduced them here. Yet this should not be the end. It’s not enough to look at only a few things and call it good. Literature is truly beyond any anthology, certainly beyond anything that I can assemble in this time and space, but there’s still so much more in the archives, waiting to be found, and read, and enjoyed.

qualities that make it worthwhile. I began with the express desire of working against the academic textbook anthology by going to complete texts myself, and so I have done. As varied as it is, going from pious the novel, sermons, biography, to frivolous comedy to amoral autobiography, I’ve formed my own anthology, my own set of important literature: I have found these works, and introduced them here. Yet this should not be the end. It’s not enough to look at only a few things and call it good. Literature is truly beyond any anthology, certainly beyond anything that I can assemble in this time and space, but there’s still so much more in the archives, waiting to be found, and read, and enjoyed.

It’s waiting for you.

Works Cited

Bellamy, Thomas. The Beggar Boy: A Novel. Alexandria: Cottom and Stewart, 1802. Print. [Dodd Center call number: A619]

Fisher, Nathaniel. “A sermon: delivered at Salem, January 14, 1796, : occasioned by the execution of Henry Blackburn, on that day, for the murder of George Wilkinson.” Boston: John Dabney, 1796. Print. [Dodd Center call number: Gaines P-1191]

Hook, Theodore Edward. The Soldier’s Return, or, What Can Beauty Do? A comic opera, in two acts. Philadelphia: Mathew Carey, 1807. Print. [Dodd Center call number: A208]

Mann, Herman. The Female Review: or, Memoirs of an American young lady. Dedham: Nathaniel and Benjamin Heaton, 1797. Print. [Dodd Center call number: A571]

Strong, Nathan. “A sermon : preached in Hartford, June 10th, 1797, at the execution of Richard Doane.” Hartford: Elisha Babcock, 1797. Print. [Dodd Center call number: WBV 1]

Tufts, Henry. A Narrative of the Life, Adventures, Travels and Sufferings of Henry Tufts, Now Residing at Lemington, in the District of Maine In substance, as compiled from his own mouth. Dover: Samuel Bragg, 1807. Print. [Dodd Center call number: A1838]

Welch, Moses C. “The gospel to be preached to all men, illustrated, in a sermon, delivered, in Windham, at the execution of Samuel Freeman.” Windham: John Byrne, 1805. Print. [Dodd Center call number: Gaines P-1195]