Sean Cashbaugh, a PhD candidate in American Studies at the University of Texas Austin and recipient of a 2014 Strochlitz Travel Grant, visited in March to conduct research for his dissertation currently titled A Cultural History Beneath the Left: Politics, Art, and the Emergence of the Underground During the Cold War. “This notion of the underground constituted a distinct political and aesthetic imaginary parallel to, but distinct from, groups like the Beats and movements like the Counterculture and the New Left,” according to Mr. Cashbaugh. Travel Grants are awarded bi-annually to scholars and students to support travel to and research in Archives and Special Collections. The following essay was contributed by Mr. Cashbaugh.

Sean Cashbaugh, a PhD candidate in American Studies at the University of Texas Austin and recipient of a 2014 Strochlitz Travel Grant, visited in March to conduct research for his dissertation currently titled A Cultural History Beneath the Left: Politics, Art, and the Emergence of the Underground During the Cold War. “This notion of the underground constituted a distinct political and aesthetic imaginary parallel to, but distinct from, groups like the Beats and movements like the Counterculture and the New Left,” according to Mr. Cashbaugh. Travel Grants are awarded bi-annually to scholars and students to support travel to and research in Archives and Special Collections. The following essay was contributed by Mr. Cashbaugh.

In his short story “The Piano Player,” poet, novelist, publisher, and musician Ed Sanders recounts the life of Samuel Gortz, an idiosyncratic musical genius living in New York City’s Lower East Side during the early 1960s. As Sanders writes, “His piano played such incredible melody lines that sometimes tears were the only response. He was a textbook example of a genius in America who shat upon convention, sell-out, compromise, acceptance.”[1] Sanders’s story is an ode to this pianist’s talents and his refusal to work and live on anyone’s terms but his own, but it is also an elegy. An impoverished musician, one living amongst a community of poor artists, he and any trace of his works disappeared: a leaky roof and a greedy landlord eager to evict an unpaying tenant destroyed his compositions; Gortz vanished. Even the building where he lived, an apartment at 13th street and Avenue C, is gone, razed, likely in the name of “developing” the always changing cityscape.

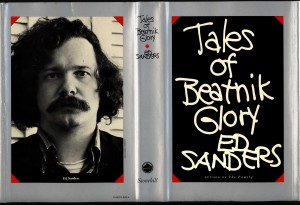

Though the Gortz Sanders recounts likely never existed, he may as well have. Sanders’s story is a call to remember all those creative figures working in New York City in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a period his novel Tales of Beatnik Glory (1975) recreates in glorious, and at times hilarious, detail.[2] It is a scholarly commonplace that New York City at this time was home to a flurry of political and artistic movements that left a lasting impression on twentieth century American culture. Of course, this was not strictly a New York phenomenon: this was happening all across the United States, in Los Angeles, in San Francisco, and in Chicago, to name only a few urban bases of wildly creative political and artistic practice. Nevertheless, as much as this decade is remembered – in scholarly tomes, in popular histories, in textbooks, or in the nostalgia of contemporary television – much is forgotten. I am thinking specifically of the Samuel Gortz’s of the era, those figures who worked outside the purview of mainstream institutions, those who never made it big, often by choice, living within the underground of the 1960s and forgotten because of it. As Sanders writes in the closing moments of “The Piano Player,” “many of those who lived on the lower east side of the 1950s and early 60s are dead, gone away opting for safety-money-‘permanence,’ gone nuts, gone gone gone.”[3]

This underground is worth dwelling upon: I think “underground” is a keyword of the era Sanders describes in Tale of Beatnik Glory; to be underground, to be a part of it, in the 1960s meant something specific. The idea of a cultural underground is familiar to us today: it usually describes a deliberately obscure cultural sphere, one that trades in various forms of subversion and transgression, relishing its position as deviant and stridently opposed to “the mainstream.” However, this is a fairly recent way to understand the concept, as artists and intellectuals never deployed the word to describe any form of culture until the 1950s, a fact most cultural historians and critics of the era have ignored. Before then, it evoked a criminal world beneath the supposedly normal American world “aboveground.” It was a criminal sphere inhabited by those dominant American culture considered “deviant,” specifically racial, sexual, and political Others. Beginning in the late 1950s, artists and intellectuals began using the term to describe their own rebellious cultural activities. By the 1960s, there were multiple, overlapping cultural milieus that self-identified in such terms: there was underground film, underground literature, underground music, the underground press, and underground comics. As Sanders suggests in his memoirs, the underground was a distinct realm of cultural practice, an imagined sphere comprised of “forbidden pleasures, underground newspapers, leftwing cells and affinity groups, underground movies, [the] mimeograph revolution, bars, coffee houses, poetry and folk music clubs, underground street culture, [and the] jazz scene – reefer.”[4] Such was the world a figure like Gortz might have lived in and moved through, and while the individual components of that world have been studied extensively, scholars have not synthesized them and only rarely consider them in relation to each other, thereby failing to theorize and historicize the concept. Artists like Sanders, however, clearly did.

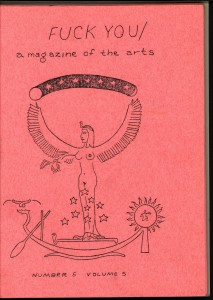

My dissertation, currently titled A Cultural History beneath the Left: Politics, Art, and the Emergence of the Underground during the Cold War, explores the idea of the cultural  underground, detailing how and why it emerged as it did. Sanders was a central figure in the scene I describe above, and his works catalogue it in all its detail. He was a filmmaker and a musician, one of the founders of underground rock group The Fugs. Famously working from a “secret location on the Lowest East Side,” he published Fuck You/ A Magazine of the Arts and operated the Fuck You Press, distributing the works of well-known authors and poets, including William S. Burroughs and Charles Olson. His Peace Eye Bookstore was one of the sites in New York City where the various threads of the underground came together. A prolific poet and writers, Sander’s works helped conceptualize an alternative sphere of culture, one imagined beneath the smooth surface of middle-class America where a diverse range of political and aesthetic practices and movements took shape. Political and legal authorities considered such activities a threat: in 1966, the New York Police Department arrested him for obscenity.

underground, detailing how and why it emerged as it did. Sanders was a central figure in the scene I describe above, and his works catalogue it in all its detail. He was a filmmaker and a musician, one of the founders of underground rock group The Fugs. Famously working from a “secret location on the Lowest East Side,” he published Fuck You/ A Magazine of the Arts and operated the Fuck You Press, distributing the works of well-known authors and poets, including William S. Burroughs and Charles Olson. His Peace Eye Bookstore was one of the sites in New York City where the various threads of the underground came together. A prolific poet and writers, Sander’s works helped conceptualize an alternative sphere of culture, one imagined beneath the smooth surface of middle-class America where a diverse range of political and aesthetic practices and movements took shape. Political and legal authorities considered such activities a threat: in 1966, the New York Police Department arrested him for obscenity.

The Ed Sanders Papers in the Archives and Special Collections at the Dodd Research Center have been an indispensable resource for my project, providing a key means by which to understand and map New York City’s underground. The collection includes a diverse range of material: unpublished manuscripts, correspondence, drafts, notes, advertisements, business records, and other ephemera. Such materials not only provide insight into Sanders’s work, laying bare the material and ideological processes that shaped their production, they also reveal the contours of the scene he was a part of.

His correspondence is especially useful in this respect. For instance, Sanders received hundreds of letters from people all over the world requesting copies of Fuck You/ A Magazine of the Arts, meaning the underground was global in scope, connected to various political and artistic communities. Using his correspondence, I can trace the circulation of publications like Fuck You, and identify specific networks of communication and exchange. It was such networks that enabled individuals to imagine something like “the underground” in first place, providing the material basis for a specific imagined community.

Specific letters can reveal a whole host of information about the sorts of relationships that existed within this community. Poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti wrote to Sanders in May of 1964, asking Sanders to collaborate on a publishing project.[5] Significantly, Ferlinghetti wrote this letter on the back of a flier for a rally held by the Bay Area Friends of SNCC in support of Civil Rights protesters in Georgia. Such a letter sheds light on the connections between the literary and artistic scenes of New York City and San Francisco, but also identifies the specific political communities these two figures allied with, collapsing any clear boundaries between the political and aesthetic.

With my dissertation, I hope help people, scholars and otherwise, remember such connections and the people that forged them. I hope to reinsert figures like Samuel Gortz back into cultural memory. Doing so fills a gap in the cultural history of American literary and political practice, highlighting a distinct way of imagining the world and engaging in cultural practice, that of the underground. Pouring through the Ed Sanders Papers at a great institution like the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center was a crucial step in that process. After all, it was there that I found “The Piano Player.” To my knowledge, it was never published. Originally slated to appear in Tales of Beatnik Glory, it was not among the eighteen stories included in the first published version of the book, nor does it appear in any later editions.[6] Though maybe forgotten in a folder in an archive, unlike Gortz’s compositions, it has not disappeared. It is not “gone gone gone.”[7]

[1] Ed Sanders, “The Piano Player,” Manuscript (Folder 215, Box 9, Ed Sanders Papers, 1973), Archives and Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

[2] Ed Sanders, Tales of Beatnik Glory (New York: Stonehill Publishing, 1975).

[3] Sanders, “The Piano Player,” 7.

[4] Ed Sanders, Fug You: An Informal History of the Peace Eye Bookstore, the Fuck You Press, the Fugs, and Counterculture in the Lower East Side (Boston: Da Capo Press, 2011), 67.

[5] Lawrence Ferlinghetti to Ed Sanders, May 20, 1964, Folder 292, Box 11, Ed Sanders Papers, Archives and Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

[6] Ed Sanders, Tales of Beatnik Glory, 2nd ed. (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2004).

[7] Sanders, “The Piano Player,” 7.