By Julie Danielson

James Marshall (called “Jim” by friends and family) created some of children’s literature’s most iconic and beloved characters, including but certainly not limited to the substitute teacher everyone loves to hate, Viola Swamp, and George and Martha, two hippos who showed readers what a real friendship looks like. Since I am researching Jim’s life and work for a biography, I knew that visiting the James Marshall Papers in Archives and Special Collections at the University of Connecticut’s Northeast Children’s Literature Collection would be tremendously beneficial. In fact, Jim’s works and papers are also held in two other collections in this country (one in Mississippi and one in Minnesota), which I hope to visit one day, but I knew that visiting UConn’s Archives and Special Collections would be especially insightful, since Jim made his home there in Mansfield Hollow, not far at all from the University. Indeed, I spent my evenings, as I wanted to maximize every possible moment during my days for exploring the collection, talking to people there in Connecticut who knew and loved Jim, including his partner William Gray, still living in the home they once shared.

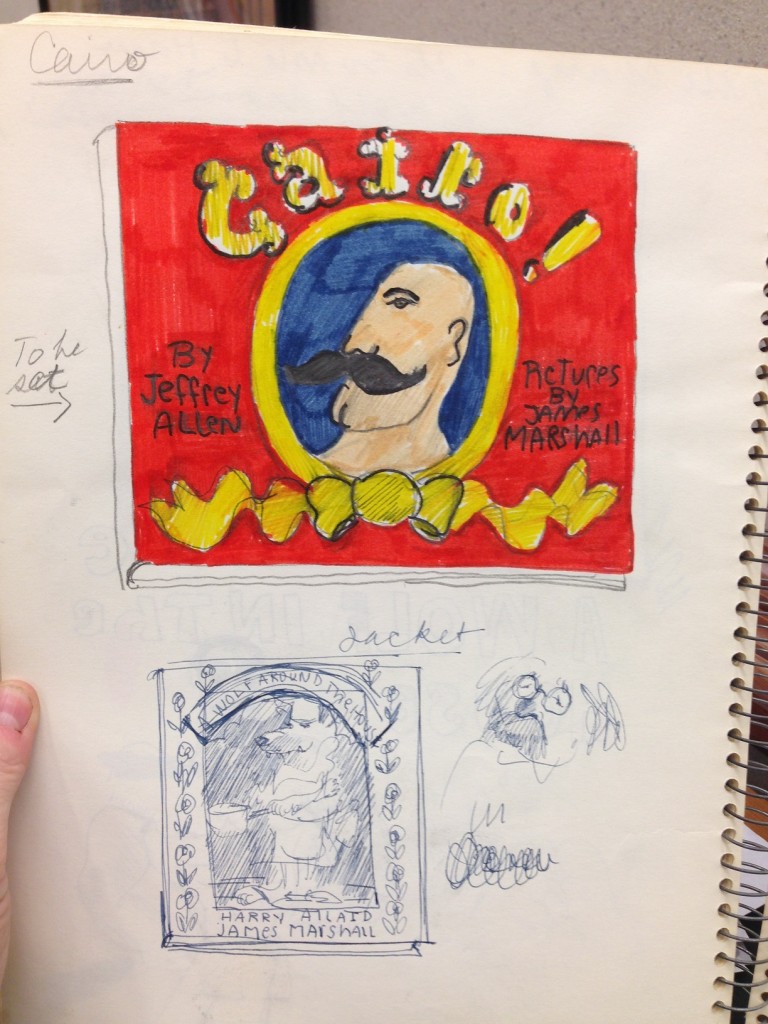

The collection is vast and impressive, just what a biographer needs. I had five full days,  thanks to the James Marshall Fellowship awarded to me, to explore the archives and see, up close, many pieces of original artwork, as well as a great deal of his sketchbooks. I saw manuscripts, sketches, storyboards, jacket studies, character studies, preliminary drawings, dummies, proofs, original art, and much more from many of Jim’s published works, including a handful of his early books — It’s So Nice to Have a Wolf Around the House, Bonzini! The Tattooed Man, Mary Alice, Operator Number 9, and more. To see sketches and art from his earlier books was thrilling, because I’m particularly fond of many of those titles. (Bonzini!, I learned in the sketchbooks, was originally titled Cairo.) Also on hand in the collection are sketches and art from his more well-known books, as well as books published at the end of his career (he died in 1992), including the popular George and Martha books and Goldilocks and the Three Bears, which received a 1989 Caldecott Honor.

thanks to the James Marshall Fellowship awarded to me, to explore the archives and see, up close, many pieces of original artwork, as well as a great deal of his sketchbooks. I saw manuscripts, sketches, storyboards, jacket studies, character studies, preliminary drawings, dummies, proofs, original art, and much more from many of Jim’s published works, including a handful of his early books — It’s So Nice to Have a Wolf Around the House, Bonzini! The Tattooed Man, Mary Alice, Operator Number 9, and more. To see sketches and art from his earlier books was thrilling, because I’m particularly fond of many of those titles. (Bonzini!, I learned in the sketchbooks, was originally titled Cairo.) Also on hand in the collection are sketches and art from his more well-known books, as well as books published at the end of his career (he died in 1992), including the popular George and Martha books and Goldilocks and the Three Bears, which received a 1989 Caldecott Honor.

To hold Jim’s original watercolors in hand is something I will never forget; as a fan of his books, I admit to getting a bit misty-eyed on more than one occasion (happy cries, to be sure). Seeing his artwork and sketches up close also afforded me rare insight into his unique talents as a children’s book illustrator, his process as an artist, his work ethic as a whole (he diligently worked and repeatedly re-worked the artwork that, in its final form, communicated an unfussy, uncluttered, and perfectly delightful simplicity) , and even his personality. This goes a long way in informing a biographer about her subject, and for that I am grateful.

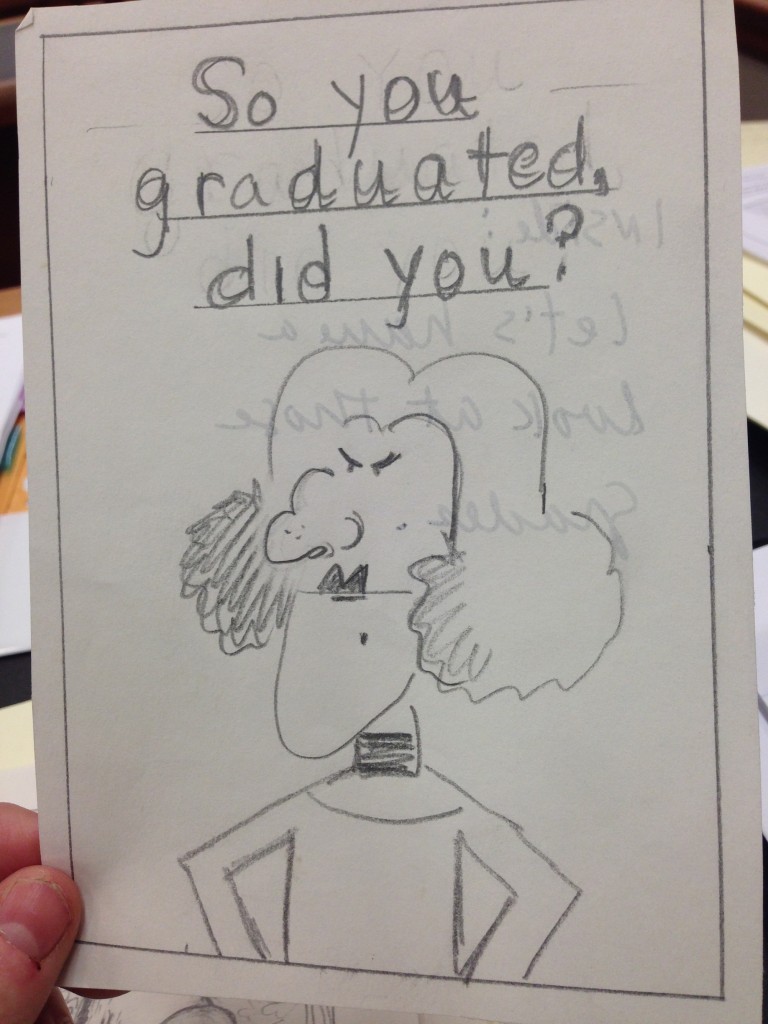

The collection also includes many of Jim’s unpublished works, including story ideas for the George and Martha books. (Readers never got to read stories about a sack race, football, fishing, and more.) There are also incomplete short stories, art for greeting cards (how I wish the one pictured here were available today; inside, it was to say “let’s have a look at those grades”),  many unidentified sketches, and much more. These unpublished works, as well as the series of sketchbooks available in the collection—there are a whole host of sketchbooks featuring both published and unpublished works—tell me a great deal about how Jim approached his work. For one, he always did so with a deep and abiding respect for children, which is my favorite aspect of his work. Never did he talk down to child readers. As Maurice Sendak wrote about Jim in an item in the collection, “never condescending to the child, allowing for freshness—sometimes rudeness—of the child’s genuine mind and heart.” In many of his sketchbooks, he also made detailed notes (illustrated, of course) about his days – what he did and whom he saw. These are intermingled with notes about book ideas. Needless to say, this is pure gold for a researcher/biographer, as are the personal papers in the collection. This includes some correspondence, an undated music book (Jim studied the viola before entering into the field of children’s books), his Caldecott Honor citation, and more.

many unidentified sketches, and much more. These unpublished works, as well as the series of sketchbooks available in the collection—there are a whole host of sketchbooks featuring both published and unpublished works—tell me a great deal about how Jim approached his work. For one, he always did so with a deep and abiding respect for children, which is my favorite aspect of his work. Never did he talk down to child readers. As Maurice Sendak wrote about Jim in an item in the collection, “never condescending to the child, allowing for freshness—sometimes rudeness—of the child’s genuine mind and heart.” In many of his sketchbooks, he also made detailed notes (illustrated, of course) about his days – what he did and whom he saw. These are intermingled with notes about book ideas. Needless to say, this is pure gold for a researcher/biographer, as are the personal papers in the collection. This includes some correspondence, an undated music book (Jim studied the viola before entering into the field of children’s books), his Caldecott Honor citation, and more.

A relatively recent addition to the collection is one that was added after the 2012 death of legendary author-illustrator Maurice Sendak. Jim and Maurice were close friends, and included in this series in the collection is a birthday book Jim once made for Maurice; books he gifted and autographed to Maurice; some of Jim’s original art, which Maurice had purchased; and more. This series told me a lot about the abiding friendship between the two, which is quite moving. It included a wooden box that contains some of Jim’s brushes and his glasses. (I find myself having to constantly remind my twelve-year-old daughter to clean her glasses, but I was able to tell her later that day, “you’re in good company. The brilliant James Marshall had smudges on his glasses as well.”) Also included is a letter from Maurice, noting the contents of the wooden box. In this letter he talks about being with Jim in July of 1992; this was about three months before Jim’s death from AIDS. Jim, unresponsive, was on his first day of morphine. “His last words … to me,” Maurice wrote, “on the telephone [had been] ‘Lovely, Loyal Maurice.’” Maurice, in fact, drew Jim as he was dying, though these drawings are not in the collection.

On my last day in Archives and Special Collections, I watched video footage of Jim speaking in one of Francelia Butler’s children’s literature courses at UConn. (Also included in the collection are Jim-related items in the Francelia Butler Collection, which were extremely helpful for my project.) It is a lecture that is, at turns, laugh-aloud funny, incisive, and smart. Jim was deliciously opinionated about others’ books. I now know first-hand how much biographers can learn from seeing video footage or hearing audio of their subjects. It was the first time I’d seen (or even heard) Jim speak.

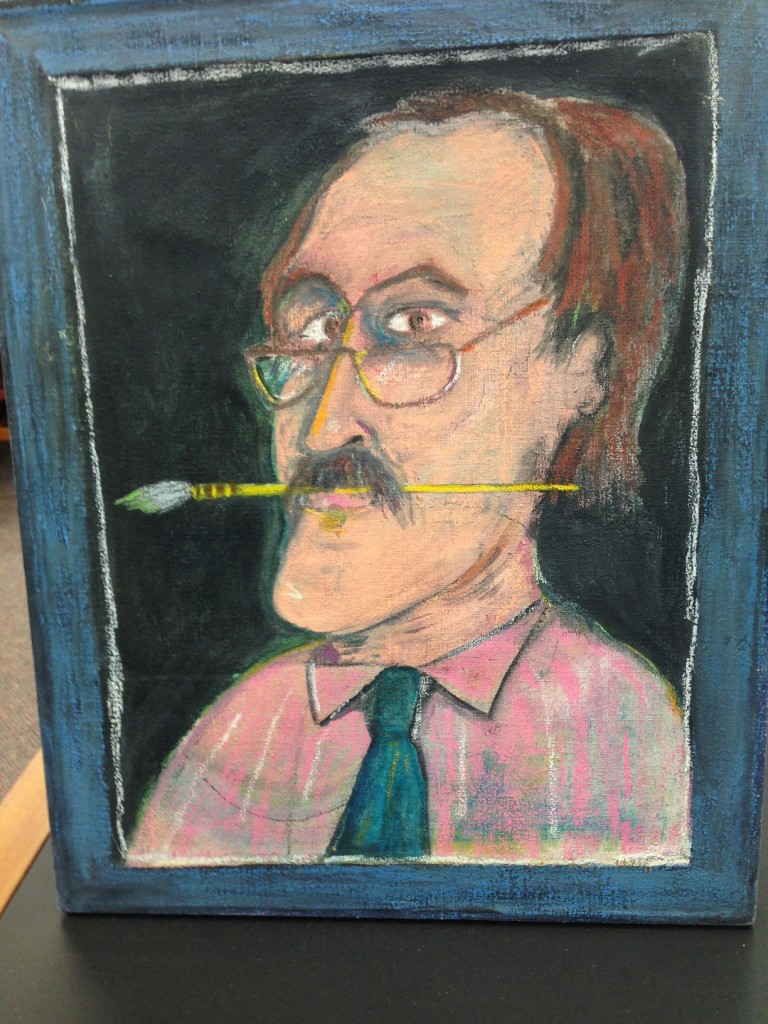

I’ll close with this rare self-portrait (on canvas), which curator Kristin Eshelman thought I’d want to see. Kristin said that Jim had painted it for his mother, with whom, I have learned, he had an affectionate yet probably complicated relationship. (He adored her and remained close to her all his life, yet she refused to accept that he was gay. She was strong-willed, and I quickly discovered that one cannot hear stories about Jim without also often hearing about her.) I love this painting. It’s happy (the pink!), a bit unsettling (note the placement of his right eye), and gloriously weird, all at once. Jim stares at us, in between brush strokes. I like to imagine he’s still here, looking askance at us just like this. With the same “genuine mind and heart” he acknowledged in his child readers.

I’ll close with this rare self-portrait (on canvas), which curator Kristin Eshelman thought I’d want to see. Kristin said that Jim had painted it for his mother, with whom, I have learned, he had an affectionate yet probably complicated relationship. (He adored her and remained close to her all his life, yet she refused to accept that he was gay. She was strong-willed, and I quickly discovered that one cannot hear stories about Jim without also often hearing about her.) I love this painting. It’s happy (the pink!), a bit unsettling (note the placement of his right eye), and gloriously weird, all at once. Jim stares at us, in between brush strokes. I like to imagine he’s still here, looking askance at us just like this. With the same “genuine mind and heart” he acknowledged in his child readers.

Julie Danielson holds an MS in Information Sciences and blogs about picture books at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast. The co-author of Wild Things! Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature, she also writes a weekly column and conducts Q&As for Kirkus Reviews. She reviews picture books at BookPage and has written for the Horn Book and the Association for Library Services to Children. She has been a judge for the Bologna Ragazzi Awards in Italy, as well as the Society of Illustrators’ Original Art Award, and she is a Lecturer for the University of Tennessee’s Information Sciences program. Ms. Danielson was awarded a James Marshall Fellowship in 2015. The James Marshall Fellowship is awarded biennially by Archives and Special Collections to a promising author and/or illustrator to assist with the creation of new children’s literature. Support is provided for research in the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection for the creation of new text or illustrations intended for a children’s book, magazine, or other publication.