Moments of student protest on UConn’s campus demonstrate the continuity and relevance of student activism for the Alternative Press Collection held at Archives and Special Collections. While the topics of protest often change with the political and social context of the moment, sometimes the similarities can be uncanny.

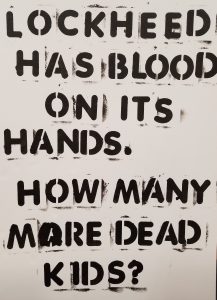

WHUS News Director Daniela Doncel reported on the student protests held during the recent university sponsored event Lockheed Martin Day:

“On Thursday, September 27, students protested the partnership between the Lockheed Martin company and the University of Connecticut due to a Lockheed Martin bomb that killed 40 children in Yemen in August, according to CNN.”

History, so the cliché goes, has repeated itself.

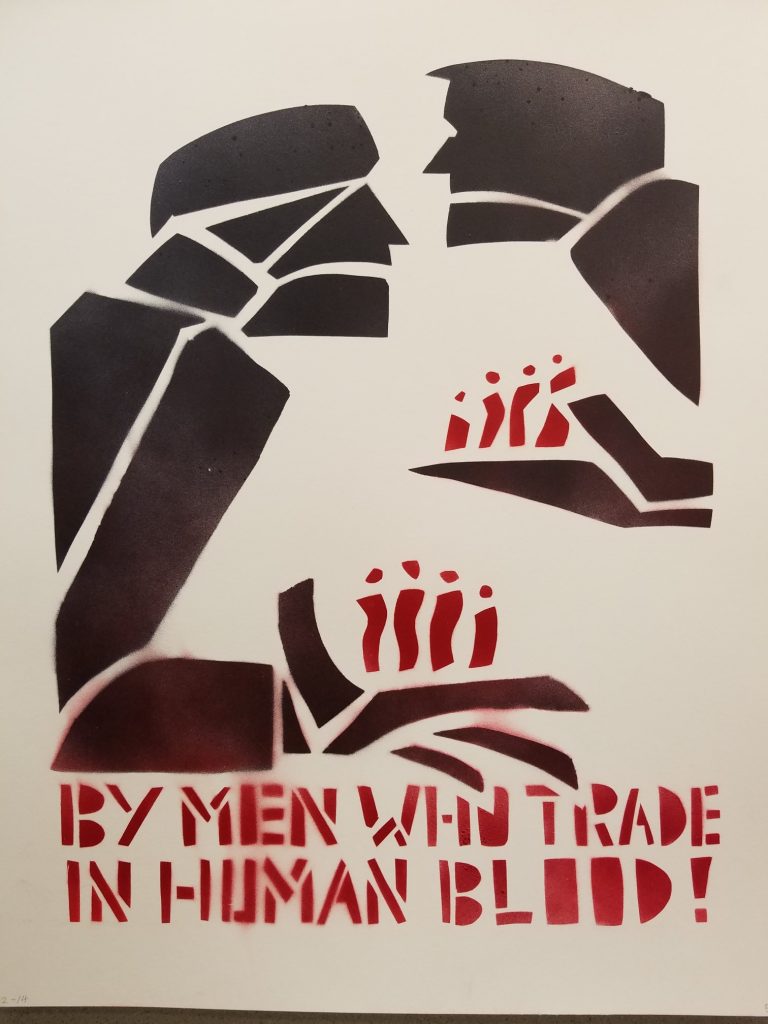

The circumstances of the Lockheed Martin’s presence on campus and the student protests resembled a smaller scale, and decidedly non-violent version, of the student and faculty protests of military recruiting that happened during the Vietnam War. In 1967 & 1968 students and faculty staged multiple sit-ins protesting the ties between the University of Connecticut and weapons manufacturers such as: General Electric, Olin-Mathieson, Dow Chemical, and Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation (which was sold to Lockheed Martin in November of 2015). In particular the recruitment attempts of Dow Chemical, a producer of napalm during the Vietnam War, and Olin-Mathieson drew large turn outs from students and faculty who thought that weapon manufacturers had no place trying to recruit students for jobs on the university campus.

In October of 1967 over 150 protesters from Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) occupied Koons hall to prevent two Dow Chemical representatives from conducting interviews with students. In December, Dow Chemical representatives did manage to conduct student interviews in the Business Administration though protesters again occupied the hallways where the interviews were taking place. The Dow Chemical Protests would be even bigger a year later when Dow Chemical representatives were slated to interview students in October of 1968,

Demonstrators celebrated the first anniversary of the 1967 Dow protest by engaging in a larger and more significant one when the company’s recruiters returned to Storrs a year later to the day…

John Manning, the assistant dean of men’s affairs, was distributing leaflets stating the official university policy concerning disruption of placement interviews. The leaflet read, “Those who would jeopardize the free conduct of university affairs jeopardize their own place in the University community.”

Bruce M. Stave, Red Brick in the Land of Steady Habits p.129

In the aftermath of the protest President Homer Babbidge would pursue disciplinary action against some of the students and faculty that participated. As a result, tensions would only increase. The protesters next move was occupying Gulley Hall, denying Babbidge access to his own office. They demanded amnesty for eight students and four faculty members that faced disciplinary consequences for their participation in protests against Dow Chemical.

The unrest from the protest was significant enough that UConn’s administration felt it necessary to address the concerns of the protesters after multiple sit-ins and multiple arrests took place. Babbidge responded with a proposed moratorium of military recruiting on UConn’s campus. UConn student protesters were not convinced.

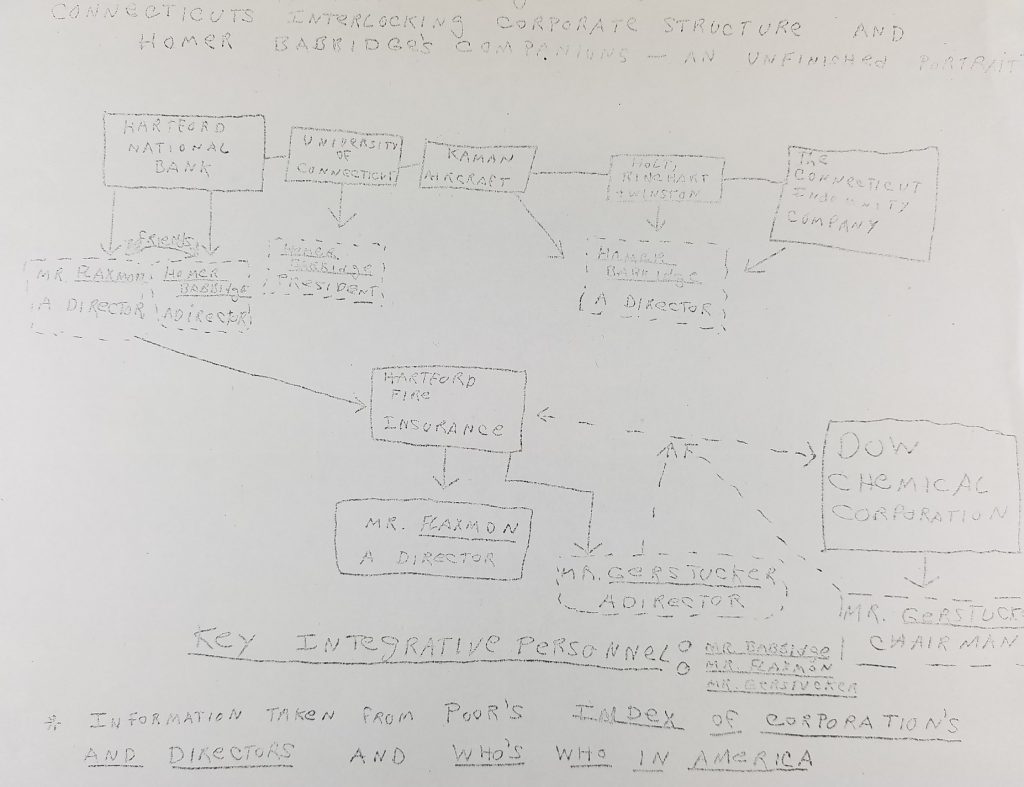

In particular the student protesters were keen to point out that President Babbidge was appointed as a director for an aerospace company with military contracts, Kaman Aircraft, and his associations between insurance and banking companies put him in proximity to the chairman of Dow Chemical in 1968, Carl A. Gerstacker. Protesters saw these potential connections as an indication of bias.

A diagram of Homer Babbidge’s alleged connections to other industry executives, produced by Students for a Democratic Society

The attempts to secure amnesty for the protesters failed to deliver any results, and tensions would come to a violent flash point when Olin-Mathieson would come to campus for recruitment interviews on November 26. The interviews were planned to be located in a former campus residence on 7 Gilbert Road. While the morning went smoothly from 9:00am to 10:00am, over a hundred protesters had crowded around the residence by 11:00am. University security officers were instructed to don riot gear after the crowd hurled bricks and other objects. One security officer was injured, and several students were injured when the security officers cleared the entrance of the house with billy clubs. The violence continued to escalate with more objects hurled through windows. After calling the State Police for assistance a security officer read “The Riot Act” ordering the protesters to disperse. The State Police showed up without badge numbers visible as they conducted arrests and dispersed the protesters.

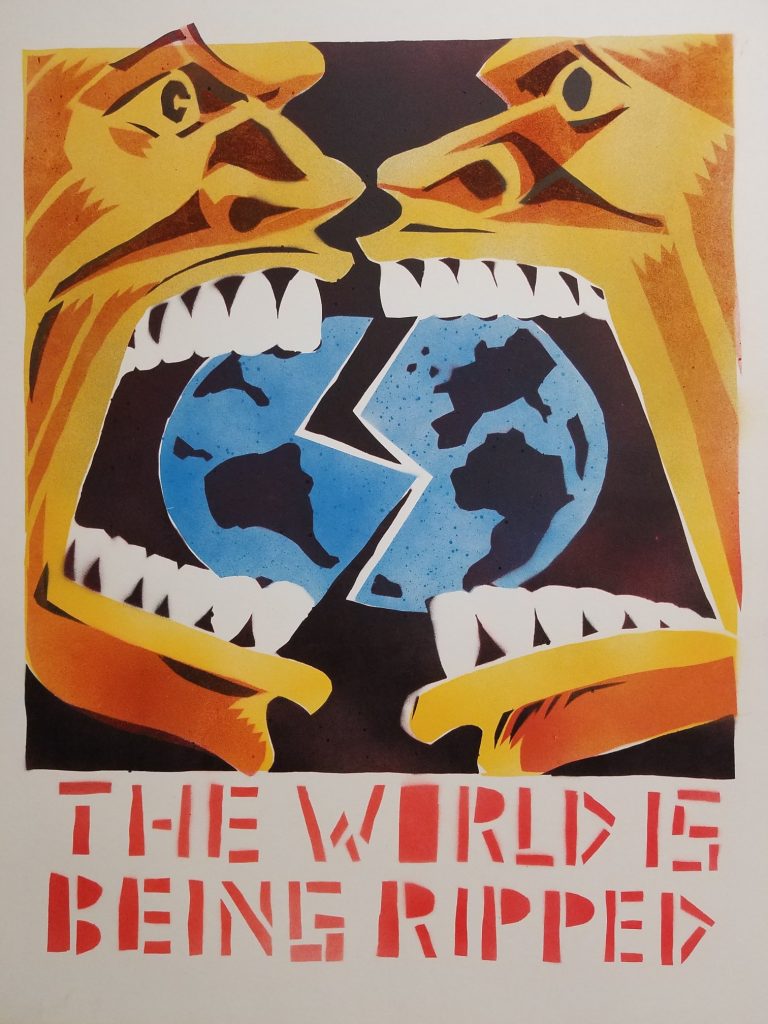

With uncanny timing, UConn’s Lockheed Martin Day and the resulting protests coincided with the Benton exhibit “What’s the Alternative?” showcasing the art and outrage of the 1960’s alternative press. The University of Connecticut Archives and Special Collections hosted an Alternative Press Open House event in conjunction with the Benton’s exhibit. The open house sought to provide a sample of materials that bridge the gap between the counter culture movements and activism borne out of and around the Vietnam war and bring it into today.

The materials at the open house sought to cover Anti-Nuclear protests, the Punk Rock movement, contemporary street art, the Occupy Movement, and the presence of white supremacy movements in Connecticut. Activism, and UConn activism in particular, is a focus for the UConn Archives Alternative Press Collection, and the trajectory of the student protests of Lockheed Martin Day helps to flesh out the continuity of protest from the sixties to today.

While the focus of the Lockheed Martin protests were similar to those of the protests from the 1960’s the differences point to some striking issues about the normalization of corporate and industrial influence within UConn’s community. In the 1960’s the idea of landing a military helicopter might have been seen as a provocative and intimidating posture for a company invested in producing military technology. However, for the UConn of 2018 it is presented as a spectacle for the curious, something inviting for those interested in the STEM fields.

While the gulf of public perception on these similar events may at first seem rather large, it seems that the materials held by the Alternative Press offer a chance to push back against this shift, signaling that the differences between 1968 and 2018 aren’t as profound as one might expect.

Related Resources:

Diary of Student Revolutionary: https://archives.lib.uconn.edu/islandora/object/20002%3A860070394

D’Archive Ep. 4 “Abbie Hoffman, UConn and the War in Vietnam”(2017): http://whus.org/2017/09/darchive-episode-4-abbie-hoffman-uconn-and-the-war-in-vietnam/

UConn Archives Alternative Press Collection: http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:19920001