[slideshow_deploy id=’8959′]

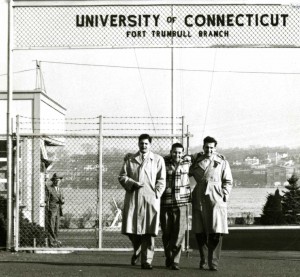

Beginning in the late 1960s, the University of Connecticut experienced a wave of unrest that rolled across the campus, leaving few areas of the university untouched. Sit-ins, demonstrations, racist incidents, canceled classes, experimental education—everything about university life in sleepy Storrs, Connecticut, seemed to be coming unmoored from its foundation.

Luckily for those who came after, UConn survived those turbulent years. Yet that intense period of upheaval, unrest, and experimentation left a lasting legacy on the Storrs campus. Much of that legacy has furnished material for the recent Archives & Special Collection exhibit, Day-Glo and Napalm: UConn from 1967 to 1971, guest curated by alumnus George Jacobi.

If the recent exhibit has piqued your interest in learning about how the 1960s shaped the University of Connecticut, Archives & Special Collections has a wealth of archival material that may interest you. Among the relevant collections are:

President’s Office Files. The collection comprises extensive material relating to each presidential administration at UConn. The records of President Homer D. Babbidge (1962–1972) are especially relevant. Many of the most significant events from this period occurred under his tenure, and his office files, as well as those from others in his administration, shed light on key events. Especially useful is the correspondence received by the president’s office, which provides insight into how community members viewed this period of campus unrest. The finding aid can be found at: https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/789

Crisis at UConn. The confluence of events at UConn in the late 1960s and early 1970s turned out to be so unprecedented that the administration commissioned a report to study the situation. The report, titled Crisis at UConn, provides useful background and supporting material on the events of the period. The finding aid can be found at: https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/324

Student and Student Organization Newspapers, Publications and Periodicals:

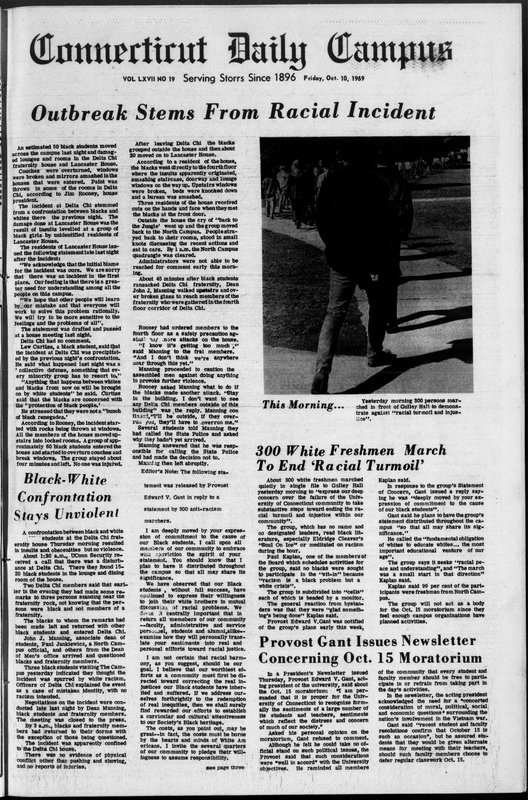

Connecticut Daily Campus and the UConn Free Press.There are few better sources to study the daily activities on campus than student publications. Especially relevant, in this respect, are the digitized copies of the Connecticut Daily Campus, the name of the student newspaper at the time (now simply the Daily Campus). Along with the official student newspaper, archivist have also painstakingly digitized alternative publications like the UConn Free Press. Digitized versions of the periodicals are available here: http://hdl.handle.net/11134/islandora:campusnewspapers

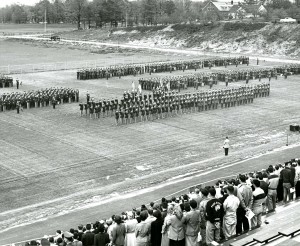

Nutmeg. Along with student publications, the Nutmeg, the University of Connecticut’s student yearbook, provides another useful source of information on this period. In particular, it provides a rich visual source for events at the time, as well as yielding significant information about student clubs, organizations, events, and the student body more generally. Digitized versions of the yearbook are available found here: http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:02653871

Inner College Collection. One product of the upheaval at Storrs during this period was the Inner College, an experiment in alternative education founded by students and faculty in 1969. This collection contains publications produced by the Inner College faculty and students documenting the radical experiment in democratic education at UConn. The finding aid can be found at: https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/971

Husky Handjob. Along with the official student newspaper, a number of alternative publications, such as the aforementioned UConn Free Press, appeared during these tumultuous years. The Husky Handjob provides an irreverent, radical alternative to the Daily Campus for researchers interested in a more direct line to the student movement at UConn. Digitized versions of the periodical are available here: http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:860224315

African American Cultural Center. Periodicals produced by staff and students affiliated with the African American Cultural Center can also usefully supplement the official and alternative publications mentioned above. In particular, the student-produced journal Contact documents black student activism on campus, such as an occupation of the university library by black students in 1974. Digitized versions of the periodicals are available here: http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20004:AACC

Alternative Press Collection. The Alternative Press Collection (APC) includes thousands of national and international newspapers, serials, books, pamphlets, ephemera and artifacts documenting activist themes and organizations from the 1800s to the present. Among the APC files can be found archival materials related to activism and unrest on campus, such as files produced by the UConn-chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), files produced by the coalition of black students (The Coalition) who occupied the UConn library, and files related to the Inner College (IC). The best way to consult the APC files is to use the card catalog available at Archives & Special Collections, though digital lists of available materials can be found here: http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:19920001APCFiles

Howard Goldbaum Collection. The photographs contained in the newly-acquired Howard Goldbaum Collection provide a rich visual document of campus upheavals in the late 1960s and early 1970s. A student photographer who worked for the Connecticut Daily Campus, Goldbaum’s photographs provide a raw, intimate portrait of campus unrest and wider student activism during the period. Digitized items draw from the collection are available here: http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:201900750078

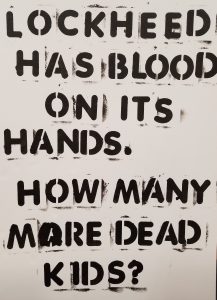

Diary of a Student Revolution. When it comes to visual material, few documents provide a more rewarding viewing experience than the documentary Diary of a Student Revolution. The film was made in 1969 for National Educational Television (NET), the predecessor to the Public Broadcasting System (PBS), and its program “NET Journal,” the forerunner of today’s PBS shows “Frontline,” “POV,” and “Independent Lens.” It documents protests led by the UConn-chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) against on-campus recruitment by companies such as Dow Chemical. A digitized version of the film is available to watch here: http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:860070394

We invite you to view these collections in the reading room at Archives & Special Collections. Our staff is happy to assist you in accessing these and other collections in the archives.

This post was written by Shaine Scarminach, a UConn History Ph.D candidate who is a student assistant in Archives & Special Collections.