While many Americans had expected for some time that sooner or later the country would be drawn into the war, the Japanese attack of December 7th nonetheless came as a shock. Even as the UConn community processed the news, ROTC alumni halfway around the world found themselves under fire. Major Maurice F. “Moe” Daly, Class of 1923, was stationed at Clark Air Base in the Philippines during the Japanese attack there on December 8th, and was eventually taken prisoner when Bataan fell the following April.

While ROTC alumni went into action overseas, the campus at Storrs underwent a significant transformation. In February 1942, the Connecticut Campus ran an article asking for volunteers to man an air raid post located atop the university water towers (located between Towers residence halls and Husky Village, torn down in 2010), and practice blackouts were conducted to prepare for potential enemy air raids. Male students and faculty members alike left in droves to join the armed forces, and by April of 1943, for the first time in the school’s history, female students outnumbered their male counterparts.

In contrast to the standardization that defined ROTC curriculum during the interwar period, the war years brought significant changes to officer training programs across the country. By September of 1942, the unit at UConn was drilling without rifles, having had to return them to the army the previous summer, and the normal summer training for advanced course Cadets had been suspended due to a lack of facilities, equipment, and instructors. In February of 1943, the advanced course was done away with altogether, with no new contracts being issued for the duration of the war. The basic course was reduced in size, and upon completion, if slots were available, Cadets would be sent to Officer Candidate School (OCS) rather than continue onto the advanced course.

The suspension stemmed from the War Department’s realization that prewar ROTC was ill-suited to meet the demands of the current situation. With the military growing at an unprecedented rate, and casualties mounting as the war escalated, the armed forces needed thousands of junior officers, and they needed them fast. To be sure, the existing pool of leaders commissioned through ROTC during the interwar period represented a valuable source of manpower and leadership during the early days of the war, but by 1942 the demand was simply too great to be met by the traditional four-year commissioning track.

ROTC Cadets prepare to receive commissions from President Jorgensen during Military Commencement Ceremonies, May 1943. This occasion marked the last full dress parade of the ROTC unit for the duration of the war.

In place of the old structure, a number of programs designed to provide the military with officer candidates, enlisted men, and technical specialists were modified or put into effect. To begin with, existing OCS programs in all branches were significantly expanded. In addition, efforts like the Navy V-12 College Training Program provided would-be midshipmen and naval aviators with a college education before sending them on to advanced training for their specific duties. UConn hosted a small contingent of V-12 men during the war, and those enrolled in the aviation program (designation V-5, later V-12A) even took to calling themselves the “Husky Squadron.”

A group of students are inducted into the Army Air Corps Reserve by Captain Raymond Flint in front of Wood Hall, October 1942.

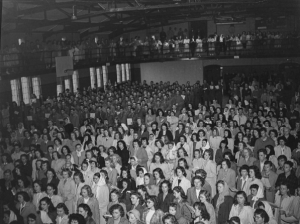

A Joint Enlisting Board, consisting of representatives from the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps, arrived at UConn in October of 1942. By the time they left, more than 500 students had joined the Army Enlisted Reserve Corps (ERC), Air Corps Reserve, and Marine Corps Reserve. In doing so, they were allowed to continue their university work until called to active service, at which point they would report for basic training. The first such groups appear to have left campus during the spring and summer of 1943.

The Army’s answer to the demand for commissioned officers and specialists was the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP). Initiated in September of 1942, it involved more than 200 universities, and like the Students’ Army Training Corps of the First World War, the idea was to provide a large pool of technically trained recruits who could go on to serve in military branches deemed vital to the war effort. Accordingly, training was focused on subject like foreign languages, medicine, and engineering. The first recruits arrived at Storrs in June of 1943, and at peak strength the unit numbered some 800 trainees. The majority of the men departed in March of 1944 for active service, and the final semester for ASTP concluded in the fall of that year.

The ASTP came to represent the largest military presence at UConn during the war. Although they lived on campus, the men were enlisted soldiers and distinguishable from regular students. They wore uniforms, marched to class, and were subject to military discipline. That’s not to say that they were segregated from the general student population, however; trainees were allowed use of university facilities, invited to sporting events and social gatherings, and given their own weekly column in the Connecticut Campus where Private John Meyer entertained readers with the antics of “Homer Sapiens, Private at the U of C.” Relations between the two groups seemed more or less amicable during the nine months the ASTP men remained on campus; the Connecticut Alumnus, commenting on the program, called them “a clean cut group of young men,” and remarked that “it is just possible that a co-ed here and there shed genuine tears at their departure.”[slideshow_deploy id=’6454′]

The widespread changes to campus were also evident on the pages of the school newspaper. Ample space in each issue was taken up by news from the front or war-related issues affecting the UConn campus. Especially common were articles detailing the whereabouts and activities of UConn alumni in the military, including many who had received ROTC commissions before the 1943 suspension. News ranged from the mundane to the tragic. The February 2nd, 1942 edition of the Connecticut Campus detailed the exploits of James “Angie” Verinis, ’41, co-pilot of the famous B-17 bomber Memphis Belle, while an October issue announced the death of Captain H.R. Freckleton, an ROTC graduate from the Class of 1935 and the first UConn alumni to die during the war.

Then there was Lieutenant Theodore Antonelli, who had received his commission through UConn ROTC in the spring of 1941. By late 1942 he was serving with a rifle company of the First Infantry Division in North Africa. During a particularly brutal assault on a German-held hill, Antonelli’s commander was wounded. Taking command of the company, he ordered his men to fix bayonets, drew his pistol, and led them in a charge up the hill. The ground was taken, but at great cost to the young officer; fragments from an enemy grenade had torn through his chest, putting him out of action for several months. He later rejoined the division and served throughout the rest of the war, earning a Purple Heart, two Silver Stars, and two Distinguished Service Medals for his actions.

Antonelli was not alone in his bravery. Many UConn graduates and ex-students would be decorated during the course of the war, including Lieutenant Colonel T.R. Philbin, Jr. who had received an engineering degree and an ROTC commission with the Class of 1940. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his daring capture of the Saar River Bridge before its intended demolition by the Germans on December 3, 1944. Such actions directly contributed to the final defeat of Germany, made official on May 8th, 1945.

At nine o’clock on that fateful morning, UConn students gathered in the Engineering building and Library to hear President Truman’s radio address announcing Germany’s unconditional surrender and the end of the war in Europe. That afternoon, a modest ceremony was held in Hawley Armory, where President Jorgensen reminded those present that while victory had been achieved in Europe, the war still raged on in the Pacific. Fighting in that theater finally ceased some three months later, and on September 2nd, 1945, the official surrender documents were signed aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. After almost four years, the war was over.

The end of the war brought a sense of relief to the Storrs campus, but also the sobering realization that peace had come at a terrible cost; by 1945, at least 114 UConn alumni had been killed in action or were missing. Four of the fourteen members of the Class of 1939 who had received ROTC commissions that year had lost their lives, and Augustus Brundage, a long-serving Professor of Agricultural Extension at the school, had lost two of his four sons (also UConn graduates.) While there were occasionally bits of good news of men previously thought dead or missing turning up alive, there were also confirmations that others would never be coming home. Moe Daly, who had endured the fighting on Bataan, the Death March following his capture, and nearly three years in captivity, was unfortunately one of the latter; word came to campus in September of 1945 that he had died aboard a prison ship the previous January.

(The Roll of Honor, which hangs in the west end of the Alumni Center on campus, lists the names of UConn alumni lost in every conflict from the Spanish-American War to the present. An online version can be found here.)

Even as it mourned the dead, however, UConn and its ROTC program looked with determination into the future. Many young men had died, but many more had not, and those who had survived were determined to come back to campus, finish their education, and get on with their lives. The influx of veterans during the postwar period signaled the beginning of another period of drastic change. Next time, we’ll follow the UConn community as it faces the trials of the Cold War and the turbulent Vietnam era, and look at some of the resulting transformations to both the campus and its Cadet battalion.

Sources

*Unless otherwise noted, all sources courtesy of Archives & Special Collections.

The Connecticut Campus, 1919-1940 (digitized through 1926)

Nutmeg (University of Connecticut Yearbook), 1923-1944

University Archive Subject file, “ROTC”

University of Connecticut Photograph Collection, Record Group 1, Series VI, Boxes 93-95

Connecticut Alumnus, Vol. 22 No. 4, 1944