They say you are who your friends are. To anyone reading Mary Clark’s 1835 signature album, this statement is almost literally true. Presumably a resident of Lowell, Massachusetts in the 1830s, we know very little about Mary’s life, except what friends wrote about her and to her in her signature album, now a part of the Diaries Collection.

Signature albums, more commonly referred to as autograph albums, are pieces of nineteenth century ephemera, commonly owned by women. In the analogous spirit of a modern high school yearbook, signature albums were used to collect personal sentiments from friends. During the nineteenth century, these sentiments “while rarely original,” generally took the form of transcribed poems about friendship, or Bible verses.[1] Friends signed, dated, and included their hometown at the bottom of each entry.[2]

The entries in Mary Clark’s signature album are not chronological. They are scattered throughout the album, separated by empty pages; all date between 1834 and 1838. Though Mary does not seem to have written in her own album, her book includes items that appear to have been created or collected by her, including a carefully drawn map of Eurasia (pictured). Female friends wrote most of the entries, though her album includes an entry from an “Oliver Brooks,” presumably a male friend.

The entries in Mary Clark’s signature album are not chronological. They are scattered throughout the album, separated by empty pages; all date between 1834 and 1838. Though Mary does not seem to have written in her own album, her book includes items that appear to have been created or collected by her, including a carefully drawn map of Eurasia (pictured). Female friends wrote most of the entries, though her album includes an entry from an “Oliver Brooks,” presumably a male friend.

Historian Anya Jabour thinks that autograph albums were particularly important to women during moments of transition in their lives, such as following commencement from school or in the weeks leading up to a marriage, allowing “young women’s friendships with each other to survive separation and even death.” [3] Mary’s album includes an undated “Quarterly Bill” (report card) from Bradford Academy, an institution in Bradford, Massachusetts, which operated as a women’s college between 1836 and 1931. Most of the entries are written by friends from Lowell, suggesting that perhaps Mary’s signature album was a way for her to stay connected with friends from home while she was attending Bradford.

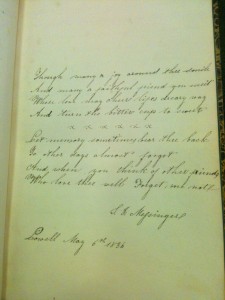

The content of the entries in Mary’s album reflects this purpose.  An 1836 entry from an “S.J. Messinger” of Lowell (pictured) includes the following handwritten poem borrowed from a Scottish author:

An 1836 entry from an “S.J. Messinger” of Lowell (pictured) includes the following handwritten poem borrowed from a Scottish author:

Though many a joy around thee smile

And many a faithful friend you meet

Whose love may cheer[e] life’s dreary way

And turn the bitter cup to sweet

Let memory sometimes bear thee back

To other days almost forgot

And where you think of other friends

Who love thee well Forget, me not!

Other entries, expressed in common language of Christian “virtue” suggest how these women conceived of, and dealt with such separations. An 1834 entry from Eliza Brooks of Lowell, MA, potentially the wife or sister of the aforementioned Oliver Brooks includes a poem, copied from an unknown source, that imagines a world where “virtue round us ever shed/The influence of her gentle light.” The poem’s author then goes on to admit that such a world will never be possible, nor desirable, for if the world was always virtuous:

We then might never thoughtful turn

Our minds to nobler scenes above,

Nor let within our bosoms burn,

Aught purer than an earthly love.

But Dearest Friends [author’s emphasis] are from us riven,

And pleasures gayest hours are brief;

And hope by stern misfortune driven,

Will wither like the Autumn leafe.

Then may we seek an endless Friend

Whose smiles are never shaded,

And hope for life that never shall end

Nor fade, as earthly scenes have faded

And calmly on life pathway move

To those Blest Mansions far above.

Eliza Brooks underlined “Dearest Friends,” in the fourth line, suggesting that this sentiment refers to Mary specifically. The “endless Friend” in this poem is assumed to be God. This poem is then one of several entries in Mary’s album recommending religion and investment in virtue, charity, and humility as ways to transcend the reality of being separated from friends, and the pain that comes with that separation. Other entries refer to virtue, Godliness, and eternal blessings outside of the context of friendship, suggesting a shared common experience and concern with upholding Christian values.

Presumably, Mary read these entries. This considered, her album becomes a dialogue between friends and herself, a place to receive and reflect on shared sentiments regarding friendship, separation, Christian virtue, and happiness.

But is this a journal? So far, I have been unintentionally vague about what I mean by a journal or diary, assuming (until now) that the term didn’t really need a definition. In my first entry, I described diaries as “something extremely personal, a continuous letter to self.” Mary’s signature album differs from previous diaries I’ve discussed in that she did not write in it, and other people did; it is not “a letter to self,” but a series of entries written to Mary by others. But it is personal, in the same way that a scrapbook or a signed yearbook is personal. The entries she collects from friends are a physical manifestation of existing friendships and interests.

Furthermore, this album differs from, let’s say, a collection of letters, in that it is contained in an album, and Mary’s presence is discernible through materials she’s intentionally inserted into it, including her map and a typed, published entry intended “For an Album” that has been removed from a primer or magazine and carefully glued to her album’s opening pages. Though Mary was not this album’s scribe, she was its owner and curator. Her album then, though not a journal, serves many of the same purposes, reminding us that diaries, in the traditional sense, are not the only self-curated historical documents that were used to record and reflect on the intimate details of a person’s life.

Rebecca D’Angelo is a senior undergraduate student in History and Anthropology. In her blog series For Private Eyes Only she studies diaries available in Archives and Special Collections at the Dodd Research Center to explore the history of journal writing and reasons why we write journals.

[1] Anya Jabour, “Albums of Affection: Female Friendship and Coming of Age in Antebellum Virginia,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 107 (1999): 128.

[2] Lisa Ricker, “Performing Memory, Performing Identity: Jennie Drew’s autograph Album, Mnemonic Activity, and the Invention of Feminine Subjectivity” (Proquest, UMI Dissertation Publishing, 2011).

[3] Ibid.

I found the poem written by S.J. Messenger in an autograph album dedicated to Sarah E. Tuller’s by Jane C Kellogg of Harwinton (Conn.) approximately 1830. Your website helped me correct a couple of words I couldn’t make out . Thank you