Blog Post 1: Author-Illustrators

As a writer, I confess to a long-held jealousy of the author/illustrator who gets to “play” with both parts of the picture book package, from idea through publication. I somehow had the idea (prejudice?) that creating a picture book is easier for these multi-talented people because they can “see” the whole project; the story (and related art) must just flow for them. I suspected that their process would not include the painstaking attention that I give to every word, and to every one of multiple variations of a story.

Although I have had several well-received picture books published, I continue to strive to improve my craft. I decided that a study of the process of author/illustrators might well help me better understand the magical interface of text and art that occurs in the best picture books. I hope my research helps improve my skill as a picture book writer, even if unlocking the secrets of author/illustrators can’t turn me into an artist.

Because I mostly write for the very young, I started my research with archival material of author/illustrator Katie Davis, who also writes for this audience. While I have only completed a review of two of her picture books, Kindergarten Rocks! and I Hate to Go to Bed!, I have already learned so much. And I have totally discarded my assumptions and prejudices.

Katie’s author/illustrator process is meticulous and time-consuming. For I Hate to Go to Bed! I studied twenty-seven dummies that Katie created. Each one included text revisions and illustration revisions, as she tweaked her story in major and minor ways. It appeared that many of these versions were done as part of her creative process before she came to the point where she was satisfied and ready to show a dummy to an editor. (I hope to interview Katie, to confirm this and ask other questions).

I now think that the author/illustrator’s job of writing a story may even be harder than mine because he or she thinks visually and can see so many possibilities.

Text and illustration revision of I Hate to Go to Bed! by Katie Davis

As a representative sample, here are several text revisions Katie played with for the opening spread of this book:

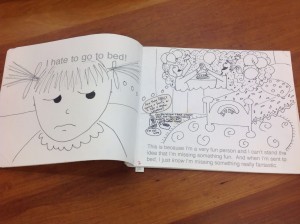

I hate to go to bed! This is because I’m a very outgoing person and I can’t stand the idea that I’m missing something. And I just know I’m missing something really fantastic.

I hate to go to bed. This is because I’m a very fun person and I can’t stand the idea that I’m missing something fun. And when I’m sent to bed, I just know I’m missing something really fantastic.

I hate to go to bed! My mama and daddy absolutely swear nothing good is happening and that I won’t miss anything but I’m not too sure.

I hate to go to bed! This is because I’m a very fun person and I just know I’m missing something really fantastic.

I hate to go to bed! Because I just know I’m missing something really fantastic.

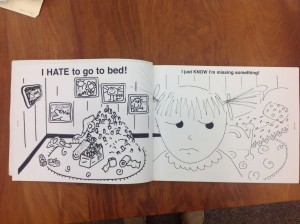

I HATE to go to bed! I just KNOW I’m missing something.

I HATE to go to bed! I just know I’m missing something!

A study of the illustrations in these many dummies reveals a similar “visual” revision process. All of the dummies show a frowning little girl (Katie captured her protagonist immediately). Some of the earliest dummies show “thought bubbles” of her parents partying after she is asleep. Others show her room with piles of toilet paper rolls (from which she later makes binoculars for spying). In some, her matching fowl (ducks/chicks?) slippers are quipping back and forth.

Here are three examples of Katie’s many illustrations drawn for the opening spread of I Hate to Go to Bed! Click on each image to enlarge.

Opening spread of I Hate to Go to Bed!, 1st dummy in Box 4: Folder 15 of Katie Davis Papers. All rights reserved. No reproduction of any kind allowed.

A later version, with simplified text:

Opening spread of I Hate to Go to Bed!, 2nd dummy in Box 4: Folder 18 of Katie Davis Papers. All rights reserved. No reproduction of any kind allowed.

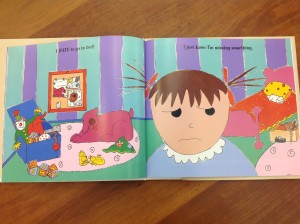

And the final opening spread found in the published book:

Davis, Katie. I Hate to Go to Bed! (New York: Harcourt Children’s Books, 1999), 4-5. Photo taken from : CLDC1438, Archives and Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries

The study of both text and illustrations reveals that Katie kept working the text and art, paring both to their essence. Her final version of the first spread immediately grabs a reader and sets the stage for the storyline to play out in a well-paced way over the rest of the book.

The frowning face of the determined protagonist remains almost identical throughout all versions of the first spread. Ultimately, that face, along with twelve words in two short sentences, clearly share her BIG problem with the reader.

Throughout the many variations of the remaining storyline, Katie explores different approaches, both with art and text, to reveal how her protagonist tackles and solves her dilemma. All versions include varied layers of meaning and humor. Sometimes, the same words, illustrated in different ways, change the plot and the story’s pacing.

How will what I’ve studied so far change my own process as an author?

I plan to slow my process down to focus more clearly on my story’s essence. I will try to pare text to get to the universal—the situation, emotion, or problem that every kid can relate to in my writing.

I hope slowing down will help me to imagine different ways the story arc might play out around the universal theme. I shall play “what if?” and “why not?” with my words in a way that will let an illustrator fill in blanks. I will strive to be less wedded to the “first” story I write; there may be other words or plot angles that offer more opportunities for an illustrator.

If I am to truly leave room for an illustrator, I need to focus even more on making every single word musical and meaningful.

Writers should make dummies as part of their process

To accomplish all of the above, or to strive to do so, I plan to create a dummy (for the text) for every story I write. I have done this with some of my manuscripts, but not all, since I have developed a good sense of story arc and appropriate length for a 32-page picture book. However, I believe parsing the text of each story I write, and placing it on the pages, will further improve my craft by encouraging me to 1) better examine what words belong on each page/spread, 2) consider whether my words allow for expansion of my story through different actions/illustrations, 3) improve forward plot motion and page turns,4) evaluate alternate story possibilities and pacing, and, just perhaps, 5) “see” more clearly how a better story might be told.

I can’t wait to start! And I can’t wait to continue my research!

![Letter from S. Hitchcock of Reidsville [possibly North Carolina] to Michael Richmond of Windham County, Connecticut, August 13, 1835](https://blogs.lib.uconn.edu/archives/files/2014/08/2014-0113_ms1.jpg)