By Richard Telford

Author’s Note: Though the product of many hours of research, writing, and revision, this chapter is nevertheless a draft; it will be subject to revision as the larger book in which it will appear takes shape. In this chapter, the very first of the book, I have departed from the time period I wrote about in the previous three chapters published on the Archives and Special Collections site, during which the Teales lost their only son, David, in wartime service. Those chapters can be accessed here. I welcome critical response, either in the comment section below or through direct e-mail. I am grateful to the Archives and Special Collections staff for providing me the opportunity to share this work, and to the Woodstock Academy Board of Trustees for awarding me a sabbatical for the 2016-2017 school year so that this work could be undertaken. Contextual information about the project and manuscript can be found here.

Prologue: Into the Beautiful, Free Country

Not only have you made us both very happy indeed; but you have also enabled us to get away from the heat and fatigue of the city into the beautiful, free country earlier than we could otherwise have done; and you know, I delight in nothing more than in being close to Nature’s heart.[1]

Helen Keller, from a letter to Alexander Graham Bell, June 2, 1899

Down the slopes of the wooded hills there came a long sighing breath that set the leaves a wavering, down the long dancing corriders of the woodland.

It told a tale of the piles of drifting snow, of fluttering grouse, and wind swept ice, of strife and har[d]ships; yet [the] trees sang on with a glad hear[t], for it told more to them than hardships and struggle, it told of gorgeous costume[s] of colored woods and fleecy sky; and so the leaves sang on, with the joy of childhood.[ii]

Edwin Way Teale, from “The Moon of Falling Leaves,” typed manuscript, ca. 1909-1910

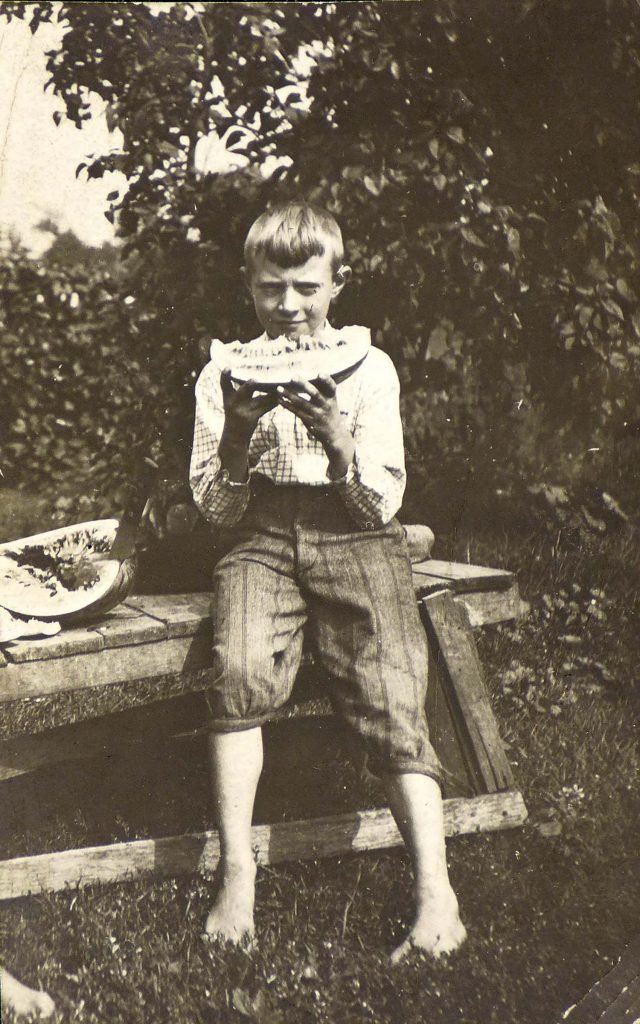

Edwin Way Teale at Lone Oak, the Indiana farm of his maternal grandparents Edwin F. and Jemima Way, circa 1910.

In 1943, amidst unprecedented slaughter that would add the word “genocide” to the common lexicon, author Edwin Way Teale introduced to the world a boy who sat perched atop the roof of his grandparents’ Indiana farmhouse, watching at once the divergent aerial paths of a bald eagle soaring on high and a gray sandhill crane hugging the earth in low, loping flight. The boy imagined what he might see through the eyes of each bird. He wondered how each might see the dune landscape, the “shining, mysterious land of gold beyond the treetops at the horizon’s edge.”[iii] Less than two miles from the roof he straddled lay a “fragment of untamed wilderness” where the boy had heard that “wolves still howled among the snow-clad dunes on winter nights.”[iv] Such wilderness stirred the boy’s imagination, and so, too, did the north woods at the edge of his grandparents’ 90-acre farm, “a mysterious realm of little trails and piles of yellow sand dug from burrows.”[v] In 1943, the world needed this boy, and the boy, now grown and suffering the trials of war, still needed that childhood world of wilderness, of unfettered exploration, of natural order, of simple beauty.

The boy, born on June 2, 1899, had entered the world as two of his future heroes, John Muir and John Burroughs, occupied adjacent state rooms on the steamer SS George W Elder en route to Alaska during the Harriman Alaska Expedition. The expedition, funded by American railroad magnate Edward Harriman, assembled the nation’s most accomplished scientists, natural historians, and artists to conduct a comprehensive two-month survey of the Alaskan coast all the way to Siberia.[vi] Of that day, when the expedition rounded the coast of British Columbia, Burroughs later wrote, “I had often seen as much color and brilliancy in the sky, but never before such depth and richness of blue and purple upon the mountains and upon the water.”[vii] On that same day, a hemisphere away, the Malolos Congress, the National Assembly of the Philippines, declared war against the United States, a war it would take the American military three years to win, at a cost of more than 4200 troops.[viii] The boy, too, would later suffer the losses of successive world wars. One of these would haunt him for the remainder of his life, would inhabit his dreams decade after decade, a perpetual “nightmare at dawn.”[ix] But that loss, on the day of his birth, was a generation removed. Finally, on the day the boy entered the world, Helen Keller wrote to her lifelong benefactor Alexander Graham Bell, to whom she would later dedicate her 1903 autobiography The Story of My Life.[x] To Bell, she confided, “I delight in nothing more than in being close to Nature’s heart,” and few statements could more aptly reflect the future trajectory of the boy clad in blue overalls, for whom the natural world would be at once a playground and a sanctuary, a nourisher and a balm. While the boy would undergo countless evolutions during the 81 years to follow, the hold of the natural world upon him would remain a constant, a holdfast in a relentless sea of waxing change.

The house at Lone Oak, the Indiana farm of Edwin F. and Jemima Way, the maternal grandparents of Edwin Way Teale, early twentieth century.

Edwin Way Teale, on the fourth page of his 1943 book Dune Boy: The Early Years of a Naturalist, revealed the identity of the overall-clad boy, who through so many trips up the shingled roof of his grandparents’ farm had left a visible trail to the ridge like “the thin trail of a garden slug.” “It was thus,” he wrote, “as the boy in the blue overalls, that I spent many hours during the long summer days of my earliest boyhood.”[xi] These summers and numerous Christmas and Easter holidays spent at Lone Oak, the 90-acre farm of his maternal grandparents Edwin and Jemima Way, formed “the most memorable months” of his childhood.[xii] Decades later, in the darkest hours of adult life, “in nights of strain and days of trouble,” Edwin would return often in memory to “the sounds of the dune country night”: the alternate refrains of katydids and crickets, the shadow-calls of nighthawks and owls, the susurrations of poultry and nesting storks.[xiii] Through the lens of time, Lone Oak became for Edwin what Tintern Abbey had been to English Romantic poet William Wordsworth, a sustaining sanctuary of memory. Amidst copious notes for his never-published autobiography, Edwin, reflecting on memories of Lone Oak, copied out the following lines from Wordsworth:

But oft in lonely rooms, and ‘mid the din

Of towns and cities, I have owed to them

In hours of weariness, sensations sweet…[xiv]

Amidst “the tensions, the pressures, the constraints, [and] the strain”[xv] of a “desperately unhappy”[xvi] childhood, Lone Oak was, and in recollection always would be, a sanctuary. “I never was free from the bridle and the bit,” Edwin wrote later, “except at Lone Oak—Dear, lifesaving Lone Oak!”[xvii]

Edwin Way Teale with his maternal grandparents Edwin F. and Jemima Way at Lone Oak, their Indiana farm, circa 1916-1918.

For Edwin, the school year spent in the industrial city of Joliet, Illinois and holidays spent at his grandparents’ dune country farm near Furnessville, Indiana divided life “into a kind of mental Arctic night and day.”[xviii] The metaphor was well chosen. The Arctic night represented a spirit-choking home life; school days teeming with bullies and marked by the chronic shadow of personal failure; an oppressive, soot-stained, limestone landscape. Sprawling along the United States Steel company’s outer rail belt around Chicago, Joliet attracted “Wire mills, coke plants, stove companies, horseshoe factories, brick companies, foundries, boiler and tank companies, machine manufacturers, can companies, bridge builders, plating factories, [and] steel car shops.”[xix] “Everything in our vicinity,” Edwin recalled later, “was begrimed and gray…, the air always scented with coal smoke.”[xx] Soot from the locomotive stacks of the Michigan Central Railroad to the north and the Eligin, Joliet, and Eastern line to the east often forced a second washing of his mother’s sheets drying on the line.[xxi] The Teales’ Washington Street home was little better. “When winter came,” Edwin wrote, “…storm windows and doors virtually sealed us in. From December to March we seemed to breathe the same dead air scented with coal gas and cooking.”[xxii] And then there was the specter of Edwin’s mother, Clara Louise Teale, whose “rigid training,” “unending inspection,” and “continual consideration of every act” he committed constrained him more than any physical landscape, interior or exterior, could have done. Her pedagogical tyranny, he reflected later, “made me turn to nature. Here was freedom, here was liberty. Here my tether was lengthened or left behind.”[xxiii]

The contrast between Joliet and Lone Oak could not have been more stark. In Joliet, inmates from the Illinois State Penitentiary carved limestone from the earth with forced labor.[xxiv] Smokestacks lined the horizon in all directions, spewing from industrial furnaces a dark cloud that blanketed the city. Images of the time, intended to extol the advanced industry of the city, instead illustrate the dual toll of corporate greed on human health and the human spirit.[xxv] At Lone Oak, clean, crisp air revealed “hills of gold shining in the sun” and “the blue hills of the Valparaiso moraine against the lighter blue of the summer sky.”[xxvi] In this land of boyhood freedom, “prevailing winds…carried quartz grains to the southeastern tip” of Lake Michigan, forming “the dunes themselves as well as the great blowouts and the small ribbed patterns on the beach sand….”[xxvii] While Joliet offered only “a haunted place beneath the smoke,”[xxviii] Lone Oak offered a place of deliverance beneath the “great clamor of the geese and waterfowl circling in the [late-day] light.”[xxix] For a boy liberated from the confines of city life, Lone Oak was as worthy a site for exploration as the Alaskan coastline was for Burroughs and Muir. At his grandparents’ farm, Edwin fixed his eyes with equal acuity on the sweep of the vast dune landscape and that of the long, emerald leg of the night-calling cicada. No titan of industry funded his expeditions. His stateroom was an attic, his steamer a rambling farmhouse, his benefactors wise and loving grandparents. The influence of Gram and Gramp Way upon him would ultimately exceed that of his own parents, and no single factor would shape more profoundly the trajectory of his life than the glorious days he spent in the beautiful, free country of Lone Oak, the childhood landscape he recalled, nearly three-quarters of a century later, as “that home of my heart.”[xxx]

Richard Telford has taught literature and composition at The Woodstock Academy since 1997. In 2011, he helped found the Edwin Way Teale Artists in Residence at Trail Wood program, which he now directs. He was a long-time contributing writer for The Ecotone Exchange. He was recently awarded a Rose and Sigmund Strochlitz Travel Grant by the University of Connecticut to support his work on a book about naturalist, writer, and photographer Edwin Way Teale. The Woodstock Academy Board of Trustees likewise granted him a sabbatical for the 2016-2017 academic year to support this work.

References

Burroughs, John, John Muir, et al. Alaska: The Harriman Expedition 1899. Facsimile: Two volumes bound as one. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1986.

“Illinois Steel Works, Joliet.” Photograph. http://trollmongo.deviantart.com/art/Joliet-IL-1900-291620595

Illustration of Joliet Iron and Steel Works, 1877-8, from advertisement in Poor’s Manual of the Railroads in the United States. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Joliet_Iron_%26_Steel_1870s.jpg

“Joliet, IL.” The Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/676.html

Keller, Helen, letter to Alexander Graham Bell, 2 June, 1899. Library of Congress, Alexander Graham Bell family papers, 1834-1974. MSS51268: Folder: Helen Keller, 1888-1918, undated.

Keller, Helen. The Story of My Life. Doubleday, Page, and Co., 1903.

“Phillipine-American War, The, 1899-1902.” Office of the Historian, Department of State, United States of America. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1899-1913/war

Renehan, Jr., Edward J. John Burroughs: An American Naturalist. Hensonville, NY: Black Dome Press Corp., 1998.

Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living: Volume II, unpublished journal, February 1944 to May 1946. Box 113, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy: The Early Years of a Naturalist. Lone Oak Edition. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1943, 1957.

Teale, Edwin Way. “Lone Oak Cat Stories.” Ca. 1909-1912. Box 84, folder 2587, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “Memories of a Bent Twig” chapter notes, drafts, 1974 July 31. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2169, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “Memories of a Bent Twig,” draft, 3-7 Aug., 1974. Most Complete Manuscript, undated. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2187, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “My Earliest Home,” draft, 28-31 July, 1974. Most Complete Manuscript, undated. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2187,

Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “My Earliest Home” chapter notes, drafts, 1974 July 31. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2168, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. Notes, Clippings, undated. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2163, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “Trail Wood” chapter notes, undated. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2186, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “Woodland Days” chapter notes, research, drafts of manuscript, correspondence, 1974 August 19. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2170, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Notes

[1] Keller, Helen, letter to Alexander Graham Bell, 2 June, 1899.

[ii] Teale, Edwin Way. “Lone Oak Cat Stories.” Ca. 1909-1912. Box 84, folder 2587.

[iii] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy: The Early Years of a Naturalist. Lone Oak Edition. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1943, 1957. 2.

[iv] Ibid. 2.

[v] Ibid. 5.

[vi] Renehan, Jr., Edward J. John Burroughs: An American Naturalist. Hensonville, NY: Black Dome Press Corp., 207

[vii] Burroughs, John, John Muir, et al. Alaska: The Harriman Expedition 1899. Facsimile: Two volumes bound as one. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1986.

[viii] “The Phillipine-American War, 1899-1902.” Office of the Historian, Department of State, United States of America. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1899-1913/war

[ix] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 8 August 1945.

[x] Keller, Helen. The Story of My Life. Doubleday, Page, and Co., 1903.

[xi] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy. Lone Oak Edition. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1943, 1957. 4.

[xii] Ibid. 6.

[xiii] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “My Earliest Home.” Box 63, folder 2168.

[xiv] Wordsworth, William. From “Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abby, On Revisiting the Banks of the Wye during a Tour. July 13, 1793.” Copied into undated notes. “The Long Way Home.” Box 63, folder 2163.

[xv] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “My Earliest Home.” Box 63, folder 2168.

[xvi] Teale, Edwin Way. “Memories of a Bent Twig,” draft, 3-7 Aug., 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 6

[xvii] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “Memories of a Bent Twig.” Box 63, folder 2169.

[xviii] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy: The Early Years of a Naturalist. Lone Oak Edition. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1943, 1957. 5.

[xix] “Joliet, IL.” The Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/676.html

[xx] Teale, Edwin Way. The Long Way Home. “My Earliest Home.” Most complete manuscript. 30 July, 1974. Box 63, Folder 2187. 2

[xxi] Ibid. 2

[xxii] Ibid. 6

[xxiii] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “Memories of a Bent Twig.” Box 63, folder 2169.

[xxiv] Ibid.

[xxv] a. “Illinois Steel Works, Joliet.” Photograph. http://trollmongo.deviantart.com/art/Joliet-IL-1900-291620595. Illustration of Joliet Iron and Steel Works, 1877-8, from advertisement in Poor’s Manual of the Railroads in the United States. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Joliet_Iron_%26_Steel_1870s.jpg

[xxvi] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy. Lone Oak Edition. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1943,1957. 4-5.

[xxvii] Ibid. 3.

[xxviii] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “Memories of a Bent Twig.” Box 63, folder 2169.

[xxix] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “Woodland Days.” Box 63, folder 2170.

[xxx] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “Trail Wood.” Box 63, folder 2186.