Carey MacDonald is an undergraduate Anthropology major and writing intern. In her blog series Through the Lens of an Anthropologist, Carey analyzes artifacts found in the collections of Archives and Special Collections.

Carey MacDonald is an undergraduate Anthropology major and writing intern. In her blog series Through the Lens of an Anthropologist, Carey analyzes artifacts found in the collections of Archives and Special Collections.

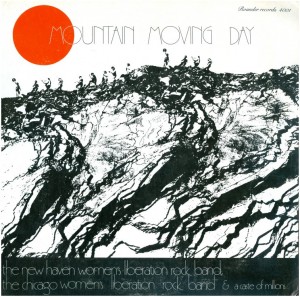

The Alternative Press Collection contains a series of LP (long-play) record albums by female musicians of the twentieth century whose music reflects the first and second waves of the women’s liberation movement. Two of these LPs are the post-first wave Mean Mothers Independent Women’s Blues LP and the second wave era New Haven and Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Bands’ Mountain Moving Day LP. Through the use of powerful, explicit lyrics and the moving techniques of blues and rock music, both LPs grapple with the issues of women’s rights, equality, and activism. They are timeless, auditory representations of the turbulent social contexts from which they came, and as such, they represent the century-long development of women’s rights awareness.

Volume 1 of the Mean Mothers Independent Women’s Blues album was produced in 1980 by Rosetta Reitz of Rosetta Records in New York, New York. According to Duke University Libraries’ Inventory of the Rosetta Reitz Papers, Reitz was a feminist writer, lecturer, and owner of Rosetta Records, which produced re-releases of female jazz and blues musicians’ songs from the early twentieth century. The LP’s gatefold cover, as mentioned by Graham Stinnett, the Curator for Human Rights Collections, contains biographical information about the female blues singers of the 1920s-1950s who are represented on this album.

Also, according to other content on the gatefold, the title’s term “mean mother” is meant as a compliment to all women, including those represented in the album, in that it is

a positive view of an independent woman, granting her the regard she deserves as one who will not passively accept unjust or unkind treatment.

The gatefold also states that these female singers were not just mourning lost love “in spite of the historic stereotyping imposed on them”, but were actually exploring every aspect of life through their music. These songs were created after the first historical wave of the women’s liberation movement ended in 1920, the year in which women were finally granted the right to vote. Yet despite the creation of this Constitutional amendment, the issue of women’s equality remained contentious. This is apparent when listening to the Mean Mothers album, which contains sixteen songs in total. For instance, Bessie Brown’s 1926 “Ain’t Much Good in the Best of Men Nowdays” laments that “married men have a tendency to roam,” while Bernice Edwards’ 1928 “Long Tall Mama” righteously claims that she is her own, independent woman and shall stand tall against adversity from men and other people in her life. On side B, Lil Armstrong’s 1936 “Or Leave Me Alone” ends with a long bluesy musical accompaniment, adding to the strength of the piece, much like Gladys Bentley’s deep, strong voice does in her 1928 song “How Much Can I Stand?” on side A.

Years later, during the second wave of the women’s liberation movement, The New Haven Women’s Liberation Rock Band and the Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band collaborated to create their 1972 nine-song album entitled Mountain Moving Day through Somerville, Massachusetts-based Rounder Records. The second wave was characterized by similar social issues pertaining to women’s rights but with particular regard to women’s equality in the workplace and a woman’s right to choose.

A woman’s right to choose is dealt with in the New Haven band’s “Abortion Song” in which Jennifer Abod and her accompanying vocalists demand for their right to choose singing, “Free our sisters; abortion is our right.” Their frequent use of “sister” works to establish a common sense of sisterhood between themselves and other women. This term is also heavily used in “So Fine” as in the lyric “Strength of my sisters coming out so fine.” While the New Haven band’s songs deal more with female sexuality, the Chicago band’s songs work to oppose stereotypical women’s gender roles in songs such as “Secretary” and “Ain’t Gonna Marry.”

Ultimately, these female bands produced music in a similar vein as their jazz and blues predecessors indicating their intent to develop and maintain a nationwide women’s rights consciousness that is rooted in the past century and yet relevant today.

Carey MacDonald, writing intern