Patrick Butler, Assistant Archivist for the Alternative Press Files Collection and Human Rights Collection, is a 2018 Ph.D. graduate of the UConn Medieval Studies Program. During his time as a graduate student he worked in the UConn Archives to broaden his materials handling experience and develop skills as an archivist. He has specialized training in medieval paleography and codicology.

On August 21, 1971, African-American activist and author George Jackson took hostages in order to escape San Quentin State Prison. Five of Jackson’s hostages: three prison guards and two inmates, died in the ensuing violence. The attempted escape ended with a prison guard shooting and killing Jackson.

Two weeks later, on September 9th, 1971 approximately 1000 inmates at the Attica Correctional Facility rioted and ultimately took control of the prison facility. The inmates took 42 staff members of the facility hostage in a bid to negotiate for prisoners’ rights. During the four days of negation, prisoners made 27 demands among which included: better medical care, better sanitation, the end of racial discrimination, updated labor policies aligned with New York State law, and the end of the violent abuse of inmates by guards and prison administrators.

While negotiations with Corrections Services Commissioner Russel G. Oswald and the Attica inmates had initial success, the dialogue would ultimately breakdown when Governor Nelson Rockefeller refused to appear at the prison in a bid to help quell the riot. In the wake of the Governor’s refusal Oswald stated that they would retake the prison by force; Rockefeller agreed.

When the New York State Police had regained control of the prison 43 people were killed, 10 of which were hostages.

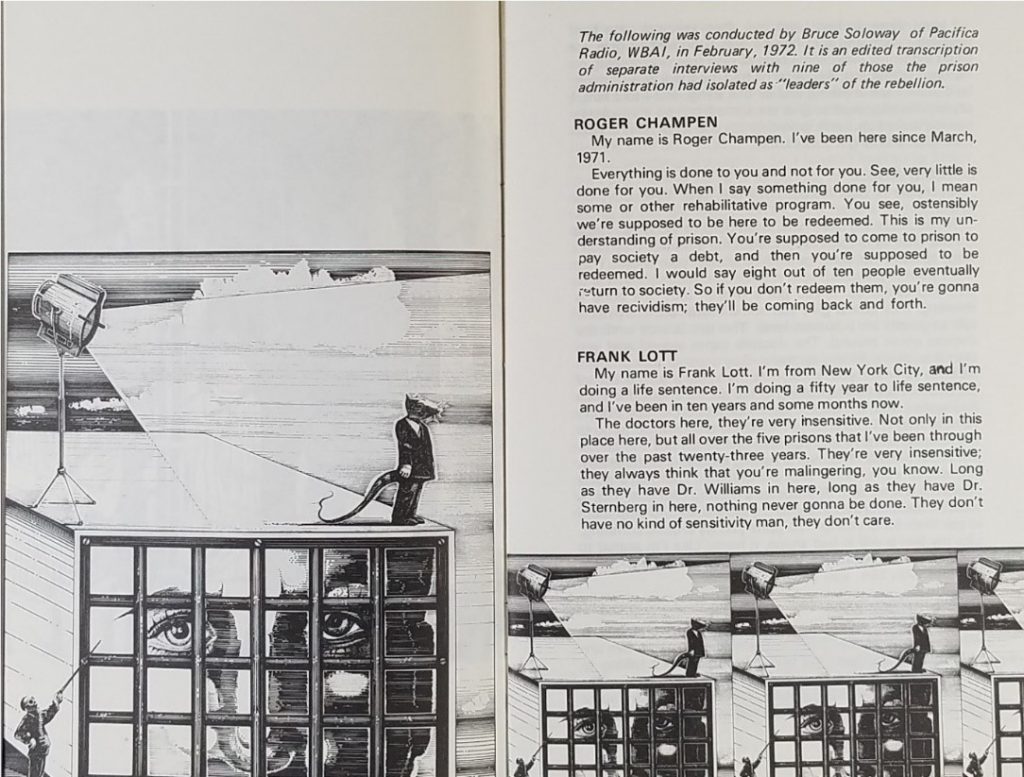

These two moments served as a flash point to bring prison conditions and prisoners’ rights into sharp focus during the seventies. However, part of the danger that comes from thinking of prisons and prisoners exclusively in terms of the violence is that it risks reducing the bodies of prisoners as little more than sites for violence. The aim of developing this exhibit has been to examine how materials within the Alternative Press Collections focus on the vulnerability of prisoners to the violence of the systems that shape their incarceration, how they respond to the systematic pressures that seek to justify subjecting their bodies to abuse and neglect, and the power that comes from forging communities in response to these pressures. A quote from an Attica inmate Roger Champen distills the physical, social, and bureaucratic pressure of incarceration succinctly and eloquently, “Everything is done to you, not for you.”

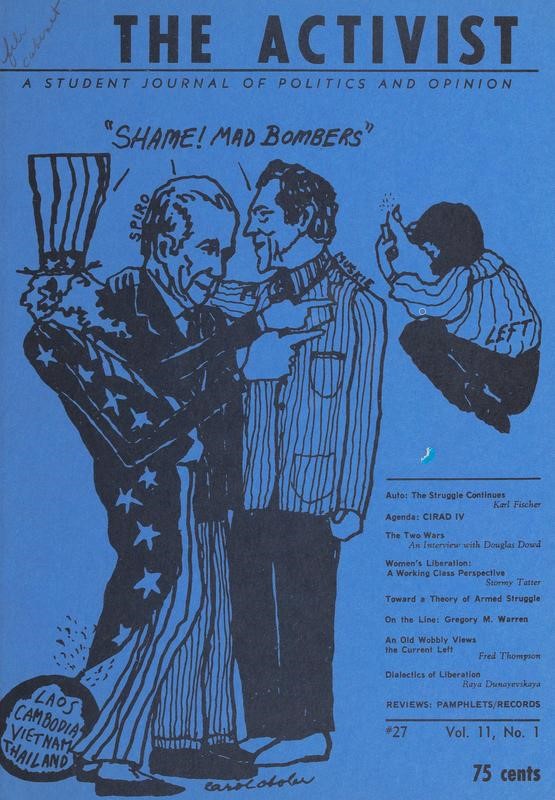

We Are Attica, 1972.

While the killing of George Jackson and the Attica Prison Riot serve as a starting point for the exhibition’s historical and social context, the materials in this exhibit come from a broad historical range and include a focus on documents produced by and for Connecticut Prisons. The Alternative Press Collection contains a wealth of material that document how prison communities develop and sustain themselves through creative writing, activism, correspondence, and even revolt. In order to accomplish this, I looked at the materials prisoners created while in prison, or shortly after leaving prison: newsletters, protest writing, creative writing, and original artwork. Even work published under the auspices of prison administrators allows for an avenue of expression and solidarity centered on vulnerability;

“To Be Black”

To be Black is to be seated

in Jim Crow vain

in the lonely south on a bus or

train

Because you’re Black and

your Blackness is symbolic of shame

To be Black is to hear a baby’s

screams in the rain

while be eaten by rats

in some dilapidated tenement

in Harlem

or some other place the same

To be Black is to see your mother’s

brow

after caring for another person’s home

somebody else’s child

the long lines of distress

strain

as they disfigure the make-up of her

frame

To be Black is to search in deep

despair

some other place

Freedom somewhere

Abdur Rahman (Clinton Fields) from Inside: Writings by Attica Inmates 1977-1978.

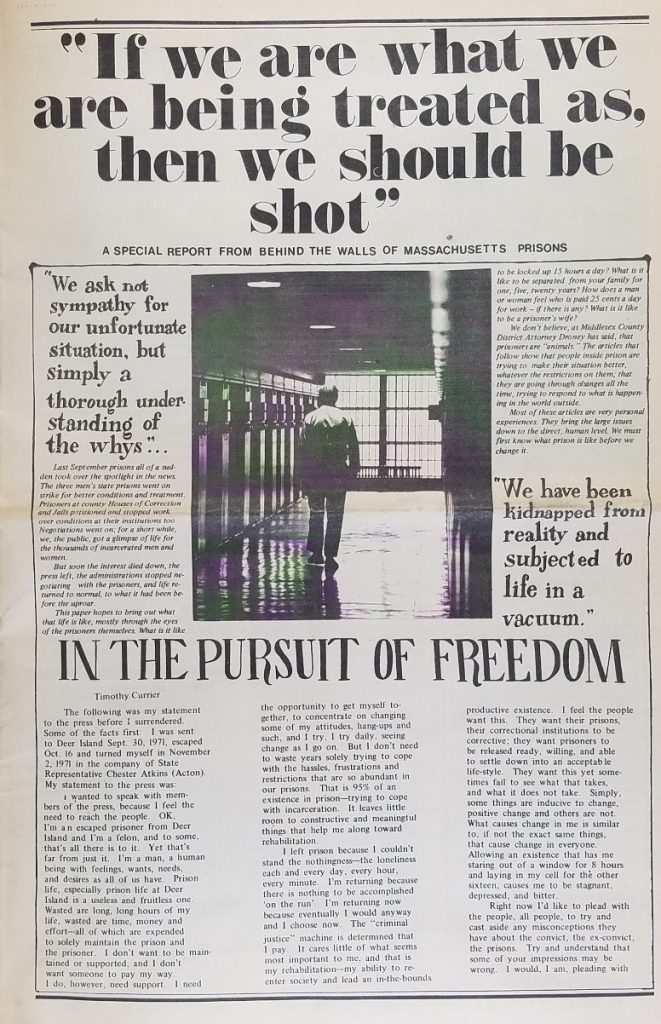

While the specific concerns of an individual piece of writing vary between violence against inmates, unjust imprisonment, political oppression, and basic human rights concerns, the language used throughout these writings, creative or otherwise is a desire for their concerns to be legible to others – to understand and to be understood. Distinct from sympathy, the specific vulnerabilities that emerged among prison writers seems to stem from a lack of acknowledgement of their embodiment as genuinely human. Almost reflexively, there is a recurrent theme to dismiss sympathy as a pressing desire among inmates. Sympathy is antithetical to the goals of these writers, a source of dismissal that does not seek to understand a fundamental connection between the prison author and the audience of the text.

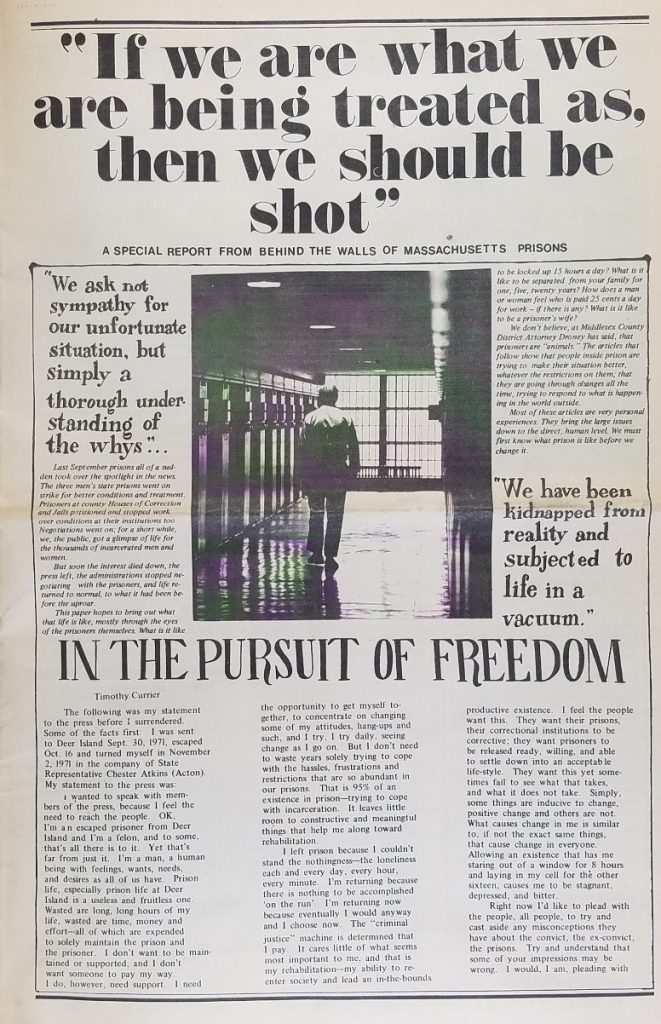

A Special Report from behind the walls of Massachusetts Prisons 1972.

The relentless desire for community, intelligibility – to not be forgotten or silenced by their isolation – makes the writings of prisoners within the Alternative Press Collection a powerful and humbling selection of materials. It holds its audience accountable for the undeniable connections that are present between individuals despite legal and societal practices of separation.

You can do two things in prison. You can be a man or you can be a robot. See, if you be a robot, you stand a very good chance of going home. But notice this, all the papers record this is a fact, that those who stay in here become submissive. When they get outside, all the things that they have inside, boil over onto society after they come back.

Roger Champen We are Attica, 1972.

The exhibition: “Locked Down and Speaking Up: Prison Riots, Reform, and Writing from The Alternative Press Collection” will be on view in the John P. MacDonald Reading Room of the Archives & Special Collections at the Dodd Research Center from June 15th – August 20th.

For more information on the Cal Robertson Papers please consult the Archives & Special Collections https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/1008