How was popular music in the late-19th and early-20th centuries distributed and heard? Prior to the advent of the home radio, music was performed at home or in public spaces and songs were published and distributed in the form of sheet music. In 1870, 1 out of every 1,540 Americans bought a new piano; in 1890, 1 out of every 874; and in 1910, 1 out of every 252, according to Nicholas Tawa in his book The Way to Tin Pan Alley: American Popular Song, 1866-1910. By the turn of the century, music publishers began to distinguish themselves. And if you wanted to hear music, you had to make it yourself.

How was popular music in the late-19th and early-20th centuries distributed and heard? Prior to the advent of the home radio, music was performed at home or in public spaces and songs were published and distributed in the form of sheet music. In 1870, 1 out of every 1,540 Americans bought a new piano; in 1890, 1 out of every 874; and in 1910, 1 out of every 252, according to Nicholas Tawa in his book The Way to Tin Pan Alley: American Popular Song, 1866-1910. By the turn of the century, music publishers began to distinguish themselves. And if you wanted to hear music, you had to make it yourself.

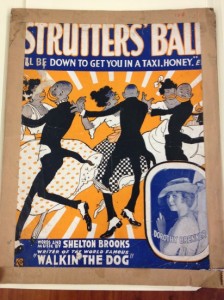

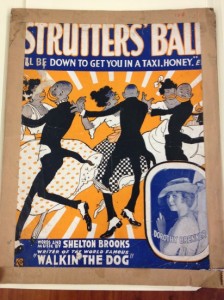

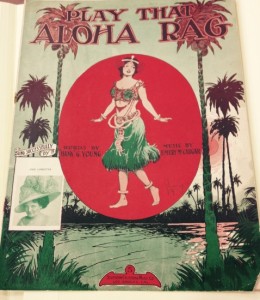

Students in Professor Robert Stephens’ course Afrocentric Perspectives in the Arts gathered in Archives and Special Collections for the opportunity to view and explore illustrated sheet music from the Samuel Charters Archives of Blues and Vernacular African American Music. Archivist Kristin Eshelman presented students with examples of published sheet music popular in the 1890s, ragtime music. Ragtime, a style of piano music, is characterized by a steady, regular bass line and an irregular or “ragged” melody. One of the most famous ragtime pieces, which nearly all of the students recognized immediately upon hearing it, is Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag”. Many of the ragtime recordings in the Charters Archive are from concerts, conventions, and meetings hosted by the Maple Leaf Club.

Students in Professor Robert Stephens’ course Afrocentric Perspectives in the Arts gathered in Archives and Special Collections for the opportunity to view and explore illustrated sheet music from the Samuel Charters Archives of Blues and Vernacular African American Music. Archivist Kristin Eshelman presented students with examples of published sheet music popular in the 1890s, ragtime music. Ragtime, a style of piano music, is characterized by a steady, regular bass line and an irregular or “ragged” melody. One of the most famous ragtime pieces, which nearly all of the students recognized immediately upon hearing it, is Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag”. Many of the ragtime recordings in the Charters Archive are from concerts, conventions, and meetings hosted by the Maple Leaf Club.

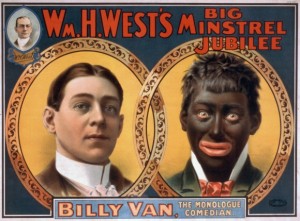

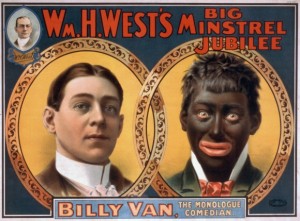

In her presentation to the class, Kristin referred to the role of minstrel shows in the dispersal and popularization of music from the 1840’s to the early 1900’s. As depicted in the Ken Burns film Jazz. Episode One, Gumbo (writer, Geoffrey C. Ward), “these shows served to codify the first body of popular American music and culture through performances all over the country.” The standard minstrel show included three parts: “the walkaround,” the “cakewalk,” and “the olio,” a variety segment including singing and dancing, novelty acts and a stump speech (Strausbaugh, Black Like You: Blackface, Whiteface, Insult and Imitation in American Popular Culture). Early minstrel shows were put on by white men in blackface and, later, black men pretending to be white men in blackface; the shows were evidence of a time where black and white Americans were constantly interpreting and misinterpreting one another.

In her presentation to the class, Kristin referred to the role of minstrel shows in the dispersal and popularization of music from the 1840’s to the early 1900’s. As depicted in the Ken Burns film Jazz. Episode One, Gumbo (writer, Geoffrey C. Ward), “these shows served to codify the first body of popular American music and culture through performances all over the country.” The standard minstrel show included three parts: “the walkaround,” the “cakewalk,” and “the olio,” a variety segment including singing and dancing, novelty acts and a stump speech (Strausbaugh, Black Like You: Blackface, Whiteface, Insult and Imitation in American Popular Culture). Early minstrel shows were put on by white men in blackface and, later, black men pretending to be white men in blackface; the shows were evidence of a time where black and white Americans were constantly interpreting and misinterpreting one another.

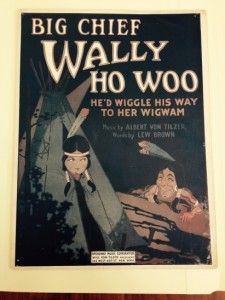

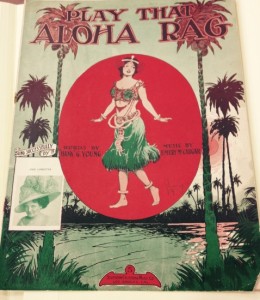

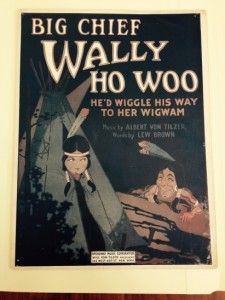

The illustrations on the covers of the sheet music functioned much like a book cover – to draw attention to the piece and entice the viewer to purchase the music. As they  examined the material, students began to key-in on the visual imagery. What is immediately apparent to the modern viewer is the prominence physical and racial stereotypes that exoticize and exaggerate aspects of essentially all non-white races.

examined the material, students began to key-in on the visual imagery. What is immediately apparent to the modern viewer is the prominence physical and racial stereotypes that exoticize and exaggerate aspects of essentially all non-white races.

Teaching assistant Marisely Gonzalez asked students to analyze the imagery, composition, content and song titles on the sheet music that were used to promote minstrel shows and ragtime music, and to compare the sheet music with an art piece from the 21st century, in either visual arts, film, theater, music or dance, by an  African American artist. What is the artist trying to communicate? She then asked students to discuss the historical context of both pieces and respond in an essay paper to the questions: what was the cultural meaning and significance of each piece? Did it provoke a public response then, and does it do so today? In March, students will present their theses and images from the assignment in class.

African American artist. What is the artist trying to communicate? She then asked students to discuss the historical context of both pieces and respond in an essay paper to the questions: what was the cultural meaning and significance of each piece? Did it provoke a public response then, and does it do so today? In March, students will present their theses and images from the assignment in class.

Archives in Action highlights how archives are being used today. Series author Lauren Silverio is an English and Psychology major and student employee in Archives and Special Collections.

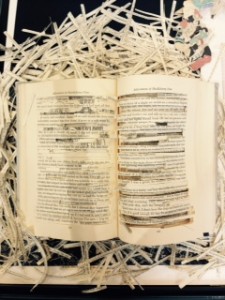

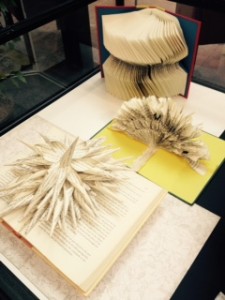

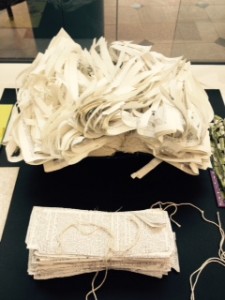

Altered books created by students in Professor Deborah Dancy’s first year studio foundation class will be on display from March 2 to March 20 in the Reading Room lobby of Archives and Special Collections. Come in and allow these altered books to lead you in your own consideration of the form and function of the modern book.

Altered books created by students in Professor Deborah Dancy’s first year studio foundation class will be on display from March 2 to March 20 in the Reading Room lobby of Archives and Special Collections. Come in and allow these altered books to lead you in your own consideration of the form and function of the modern book. about the book as an object of information and of art. Students draw inspiration from nature – cascading waterfalls, leaves, feathers, flowers, and rolling seas – as well as from the clean lines of geometry and the rhythm of repetitive shapes.

about the book as an object of information and of art. Students draw inspiration from nature – cascading waterfalls, leaves, feathers, flowers, and rolling seas – as well as from the clean lines of geometry and the rhythm of repetitive shapes. Other students chose to alter the books so that they expanded beyondtheir original physical boundaries, transforming the printed page into a three-dimensional sculpture.

Other students chose to alter the books so that they expanded beyondtheir original physical boundaries, transforming the printed page into a three-dimensional sculpture.

African American artist. What is the artist trying to communicate? She then asked students to discuss the historical context of both pieces and respond in an essay paper to the questions: what was the cultural meaning and significance of each piece? Did it provoke a public response then, and does it do so today? In March, students will present their theses and images from the assignment in class.

African American artist. What is the artist trying to communicate? She then asked students to discuss the historical context of both pieces and respond in an essay paper to the questions: what was the cultural meaning and significance of each piece? Did it provoke a public response then, and does it do so today? In March, students will present their theses and images from the assignment in class.