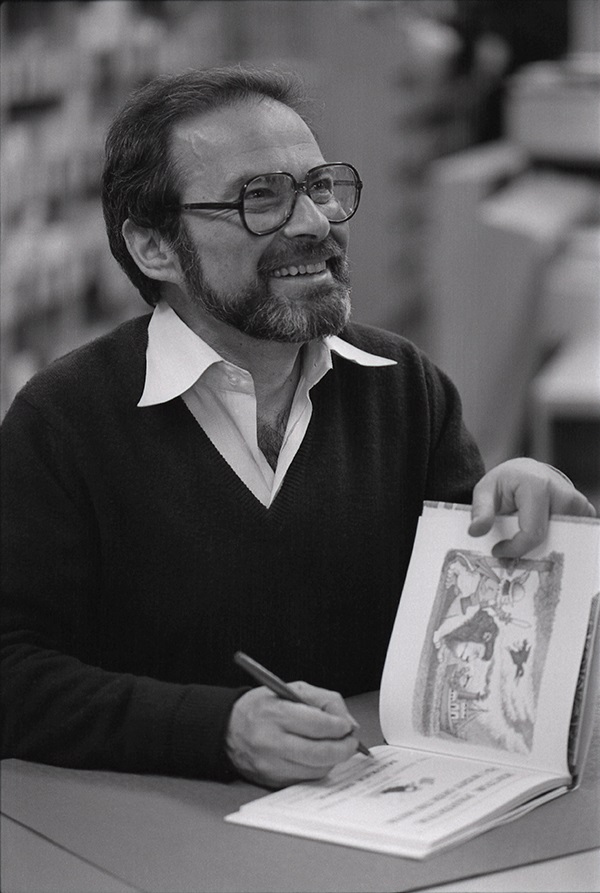

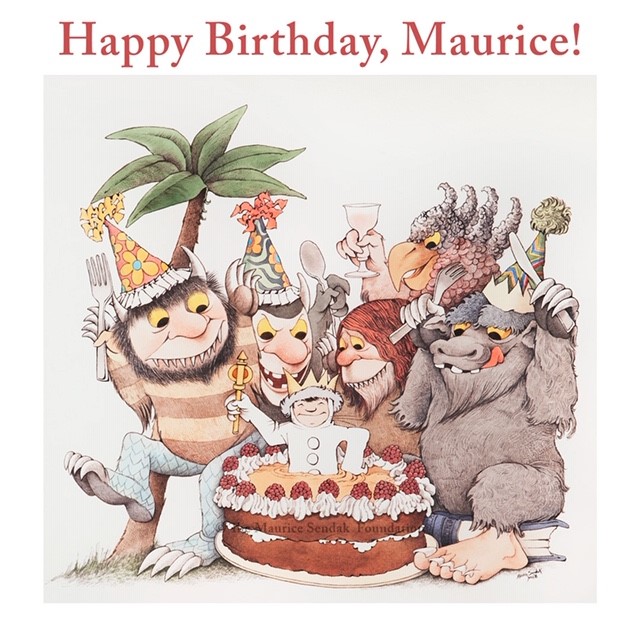

Today marks what would have been Maurice Sendak’s 92nd birthday and the 8th anniversary since his death on May 8, 2012. Born in Brooklyn, New York, on June 10, 1928, Maurice Sendak was a largely self-taught artist who went on to illustrate over 100 books during his sixty year career. Books for which Sendak became singularly identifiable include Nutshell Library (1962), Where the Wild Things Are (1963), In the Night Kitchen (1970), Outside Over There (1981), and many others. He was honored with numerous awards, including the international 1970 Hans Christian Anderson Award, the 1983 Laura Ingalls Wilder Award given by the American Library Association, the 1996 National Medal of Arts, and the 2003 Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award. Sendak was the 1964 Caldecott Medal Winner forWhere the Wild Things Are.

He later held a second career as a costume and stage designer in the late 1970s, completing work on operas by Wolfgang Mozart, Sergei Prokofiev, and Maurice Ravel. Of music, Sendak said in a 1966 interview produced by Morton Schindel at Weston Woods Studios in Weston, Connecticut:

“I do most of my work to music, and music plays an extremely important part in my work. Depending on what I’m doing at the moment, there is always a specific kind of music I want to listen to. All composers have different colors, as all artists do, and I kind of pick up the right color from either Haydn or Mozart or Wagner while I’m working. And very often I will switch recordings endlessly until I get the right color and the right note and the right sound and then settle down happily to whatever I’m doing.”

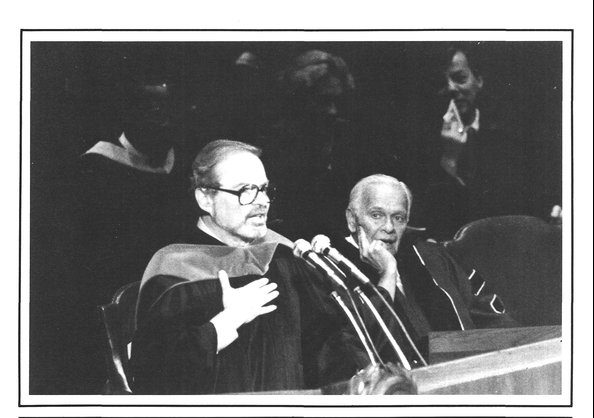

Maurice Sendak moved to Ridgefield, Connecticut in 1972 with his partner, psychoanalyst Dr. Eugene Glynn. He supported the University of Connecticut for many years, speaking to the children’s literature classes of Professor Francelia Butler in the 1970s and 1980s and making important contributions over the years to support the legacy of Professor James. On September 5, 1990, Sendak was the recipient of an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts at UConn.

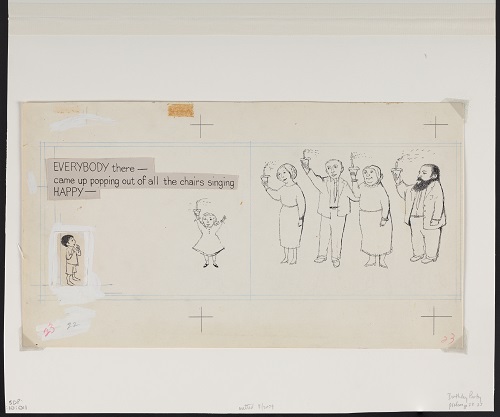

To honor Maurice Sendak’s birthday anniversary, it feels appropriate to celebrate with The Birthday Party (1957), one of eight collaborations between Sendak and children’s book author Ruth Krauss (1901-1993) between 1952 and 1960. The Birthday Party follows a young boy, David, who “had been everywhere” except to a birthday party. He arrives home one day and after searching through the rooms in the house, finally finds everyone in the dining room singing “Happy Birthday dear David” and only then does he realize that not only is he at a birthday party but that the birthday is his own.

Sendak reflects on his relationship with Krauss in the 1994 obituary “Ruth Krauss and Me: A Very Special Partnership”:

“Ruth wasn’t so patient, or quiet, and she could frighten me with her stormy tirades. It was hard for such a fiercely liberated woman to contend with a potentially talented but hopelessly middle-class kid. In the end, she slapped me into shape — almost literally. When Ruth approved of a sketch, I was rewarded with the pleasure of her deep belly laugh, which rose upward and exploded in little-girl giggles. But her disapproval could be devastating…

…My favorite Krauss is A Very Special House, published in 1953. That poem most perfectly simulates Ruth’s voice — her laughing, crooning, chanting, singing voice. Barbara Bader, in her American Picturebooks from Noah’s Ark to the Beast Within (Macmillan), sums up that text: “It runs on, it erupts, it runs together — like a dream, daydream or nightdream or playdream; and the disarray, the flux, the indeterminacy were essential to the personal and private fancies that were to chiefly occupy Ruth Krauss thereafter.” “Thereafter” was the series of books Ruth and I collaborated on, eight in all. They permanently influenced my talent, developed my taste, and made me hungry for the best. But nothing was so satisfying as A Very Special House; those words and images are Ruth and me at our best. If I open that book, her voice will laugh out to me. So I will leave it shut a while.”

The Birthday Party charms. A petite book accordingly sized for children’s hands, the images consist of ink drawings with yellow and grey washes. David wanders alone from a scene of a beach, the woods, and a street corner until he reaches the party and suddenly, turning from one page of David peering into a dark room to another, everyone comes into full view. He is surrounded by smiling adults and a young girl, candles set in cupcakes raised high in the air. Sendak’s imagery captures Ruth Krauss’ playful use of rhythm and David’s surprise, delight and joy.

The Birthday Party is a gentle reminder to celebrate the special days of one’s life and to cherish those fleeting moments. Happy Birthday, dear Mr. Sendak!