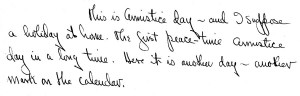

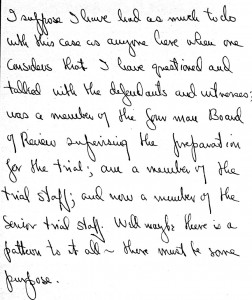

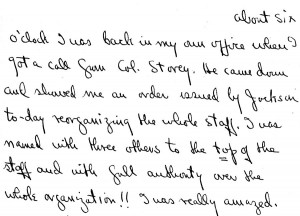

Courtesy of guest blogger, Ambassador Stephen J. Rapp This slideshow could not be started. Try refreshing the page or viewing it in another browser. Courtesy of guest blogger, Olga Touloumi Design played an important role in the preparation of the Nuremberg Trials, setting up the character of the proceedings and producing a model for future war crimes tribunals. In May 1945, a memorandum reached the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), asking designers to build the case for the prosecution of “the leaders of the European Axis.” OSS’s Presentation Branch, which had been providing the War Department with design services, agreed to partake the production and organization of “evidence” in coherent legal arguments.[1] Dan Kiley, soon to become one of the most celebrated American landscape architects, led the team. The directives asked for a space where the cases would be “clearly presented, expeditiously handled, and well reported to the world at large,” with accommodations for the “inconspicuous” presence of the mass media to render the trial a global event.[2] “This is Armistice Day–and I suppose a holiday at home. The first peace-time Armistice day in a long time. Here it is another day–another mark on the calendar.” [p. 192, 11/11/1945] Tom Dodd spent the holiday working in an effort to “hasten these proceedings along” rather than sitting out in the cold watching two service teams play football. [p.192] The middle weeks of November saw regular clashes between General Donovan and Robert Jackson regarding the best way to present and try the case–Donovan preferring to emphasize witnesses and Jackson documents. Dodd felt caught in the middle. He liked both men and understood their individual perspectives while trying to stay out of the fray. As the week wound down, he reflected, “Really Grace, the evolution of my participation has been a most amazing thing to me. I suppose I have had as much to do with this case as anyone here when one considers that I have questioned and talked with the defendants and witnesses, was a member of the four-man Board of Review supervising the preparation for the trial, am a member of the trial staff, and now a member of the senior trial staff. Well maybe there is a pattern to it all–there must be some purpose.” [pp. 193-194, 11/13/1945] The real beginning of the trial loomed and the purpose had yet to be determined. –Owen Doremus and Betsy Pittman [Owen Doremus, a junior at Edwin O. Smith High School, is supporting this blog series with research and writing as part of an independent study.] The majority of the letters from Tom Dodd to his wife Grace have been published and can be found in Letters from Nuremberg, My father’s narrative of a quest for justice. Senator Christopher J. Dodd with Lary Bloom. New York: Crown Publishing, 2007. Images available in Thomas J. Dodd Papers. As October came to a close, the foliage in Connecticut and in Nürnberg were putting on the usual autumn display. Dodd remarks in his letters to Grace that,”It makes me homesick to read of your walks on the country roads with all the beautiful foliage about you. I love the fall of the year and most of all I love a New England fall…” [pp. 183-184, 10/29/1945]. As much as he misses home, Tom shares his hopes that the beautiful fall will lead to a mild winter. “Yesterday was a nice fall day–clear and mild–if this weather continues these Germans will be fortunate. Let us hope they have a mild winter for if it is severe many will perish.” [p. 186, 11/2/1945] Dodd is less sanguine about the upcoming trial. “I will not list the countless little and big problems–suffice it to say they are innumerable…What this organization really needs is about 6 tickets–one way–to New York” [pg. 186, 11/2/1945]. Several days later, the frustrations remain but his writing has a new direction. “The pressure is on for fair now. Today Jackson published a memorandum naming trial counsel–and–I was included with nine others.” [p. 189, 11/5/1945] His concluding comments in his letter of 5 November reiterates his ongoing, and conflicting feelings about his contributions and the trial itself. “It seems strange to me that I should be catapulted onto this trial staff. Maybe it is a great opportunity. The world will watch this case–and in my judgment it will make history…I hope I can do a job that will be worthwhile.” [p. 189, 11/5/1945] –Owen Doremus and Betsy Pittman [Owen Doremus, a junior at Edwin O. Smith High School, is supporting this blog series with research and writing as part of an independent study.] The majority of the letters from Tom Dodd to his wife Grace have been published and can be found in Letters from Nuremberg, My father’s narrative of a quest for justice. Senator Christopher J. Dodd with Lary Bloom. New York: Crown Publishing, 2007. Images available in Thomas J. Dodd Papers. As the opening of the trial approached, Tom Dodd saw his role at Nuremberg coming to a close. He was finalizing interrogations and making plans to leave Germany. All that changed in the evening of October 22, 1945. “This has been a rather unusual day,” he wrote to Grace. “About six o’clock I was back in my own office when I got a call from Colonel Storey. He came down and showed me an order issued by Jackson today reorganizing the whole staff. I was named with three others to the top of the staff and with full authority over the whole organization!! I was really amazed.” [pp. 177-178, 10/22/1945] Continue reading As established by the agreement signed in London the previous August, the Tribunal opened on 18 October 1945 in Berlin. While back in Nurnberg, Tom Dodd is meeting with the staff on the law of conspiracy, wrapping up his interrogations and anticipating his return to Connecticut in November. “Start telling our friends that I hope to home in November–and I cannot stay for the trial.” [p. 173, 10/18/1945] The official trial wasn’t scheduled to begin until November, but the interrogations were scheduled to be completed by 17 October. In addition to wrapping up with Keitel about his activities in Poland, Thomas Dodd and Father Walsh questioned General Boettcher. A frail old man and former military attaché to Washington, D.C., Boettcher had a married daughter living in Buffalo (NY), a wife and daughter missing in Russian occupied Leipzig and was questioned because he had listened to broadcasts from the U.S between 1942 and 1945. Tom later wrote to Grace, “I feel very badly for him—if he is a war criminal so am I” [p. 162, 10/8/1945]. Continue reading Threaded through the renewed hope for the future demonstrated by the recovery of France and preparations for the upcoming trials in Germany, Dodd reflected on October 2 that “I sometimes feel depressed about the future. Many well-informed people over here say another war is inevitable–already we are laying the foundation for it.” [p. 154, 10/2/1945]. Observations of the actions and attitudes of his colleagues on the other prosecution teams did not bode well but Dodd resolved “to stand openly and firmly against this menace.” [p. 155, 10/2/1945] Meetings, desk work, interrogations, staff changes, lunches, dinners and the occasional evening entertainment filled the time as the days passed and became “ordinary.” Continue reading On September 25th, Dodd had a breakthrough in his questioning of Dr. Scheidt. Scheidt had been questioned repeatedly about the OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht) files, insisting each time that he burned them all. Dodd’s relentless interrogation paid off when he was able to make Scheidt admit,” All right, I buried some of the most important ones at Berchtesgarden” [p.142, 9/25/1945]. The admission was significant. The existence of even a portion of the files was of unimaginable value and had the potential to be a huge break for the prosecution. Despite his many contributions similar to the one with Scheidt, Dodd saw himself pushed to the side as the staff expanded. As of 24 September 1945, the United States legal team had grown to approximately 250 people and according to Dodd 150 of those were “superfluous and worse” [p. 141, 9/24/45]. As he explained to Grace,” I am no one’s fair-haired boy, I am not in the military, and it is a mess anyway” [p. 142, 9/25/1945]. At this point, it seemed as if Colonel Brundage and Dodd were the only ones making advances on any of the interrogations, and yet two felt that others shared information only grudgingly, if at all. Continue reading The growing staff of the International Military Tribunal was preparing to prosecute individuals held responsible for some of the most horrific, gruesome, and bloodcurdling actions during WWII. The environment of the court was becoming increasingly intense and professional with the lives of many on trial for those actions. Many of the military men, as well as those investigating and working for the prosecution teams, took the time to create or balance the daily exposure to chilling facts of the Nazi regime with more pleasant activities during their time in Germany. Dinner parties, traveling, or attending performances at the opera house became regular occurrences as the staff settled in and became better acquainted with one another. On 15 September 1945, Colonel Amen held a cocktail party for himself and ten others including Jackson, the man who selected Dodd for the U.S. team. The event included a private dinner party at the hotel. Dodd informed his wife, “It is quite informal and it does make life in this atmosphere at least bearable” [p. 129, 9/15/45]. Four days later on the 19th of September, Colonel Corley hosted a dinner party of his own at the Herr von Faber Castle, which was designed with a marvelous 80 rooms, and contained a prominent orchestra welcoming the guests as they entered the majestic Castle. Continue reading Building the Case for the Nuremberg Trials [70 Years After Nuremberg]

Armistice Day 1945 [70 Years After Nuremberg]

Tension mounts [70 Years After Nuremberg]

A Rather Unusual Day [70 Years After Nuremberg]

Opening of the Trial [70 Years After Nuremberg]

Final Preparations [70 Years After Nuremberg]

A New Normal [70 Years After Nuremberg]

A Brief Respite [70 Years After Nuremberg]

A Balanced Life [70 Years After Nuremberg]

Prosecuting “Men Who Possess Themselves of Great Power”: The Revolutionary Legacy of Nuremberg [70 Years After Nuremberg]

Reply