Abandoned tower at the Cedar Hill Rail Yard, by Matthew Chase, 2022

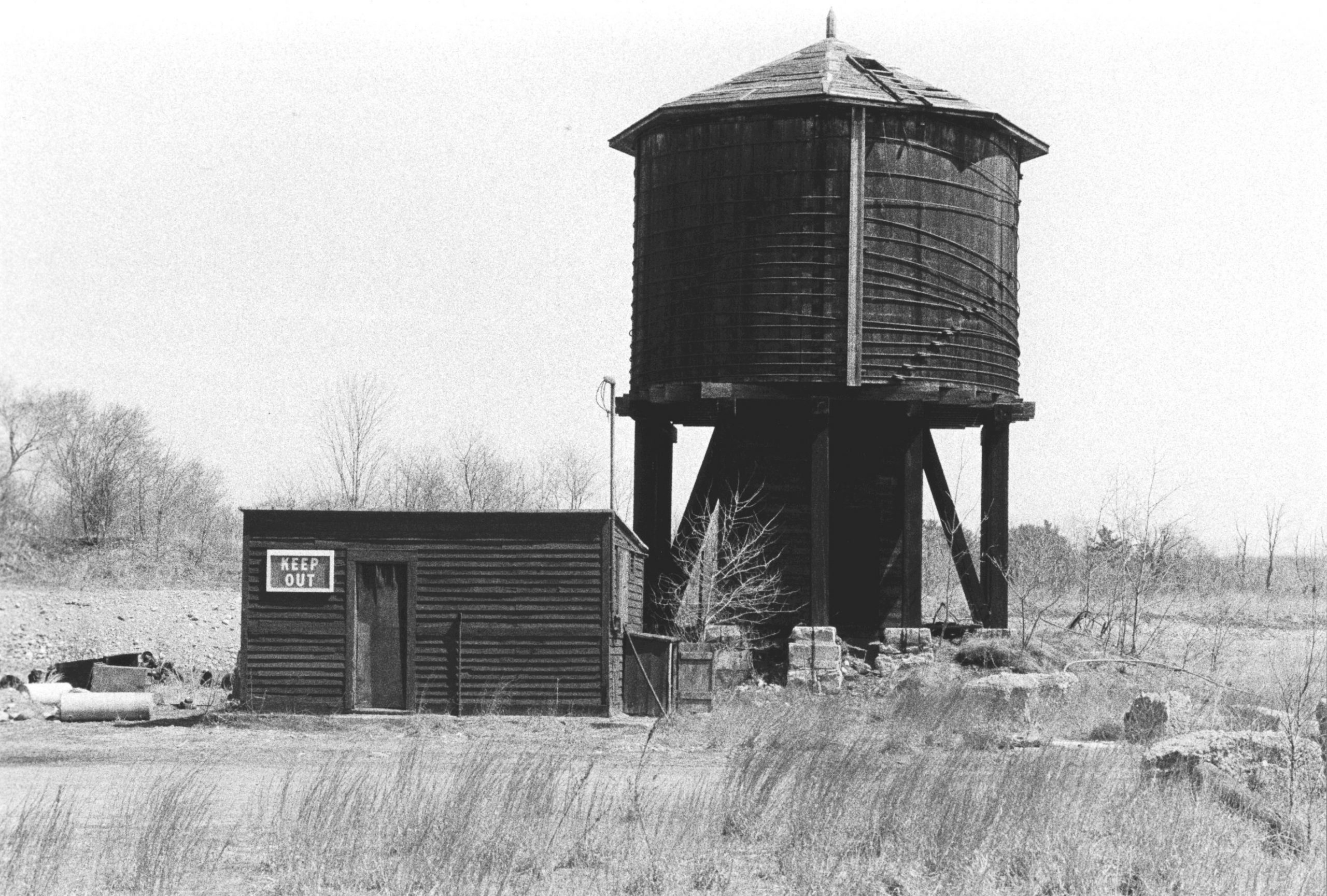

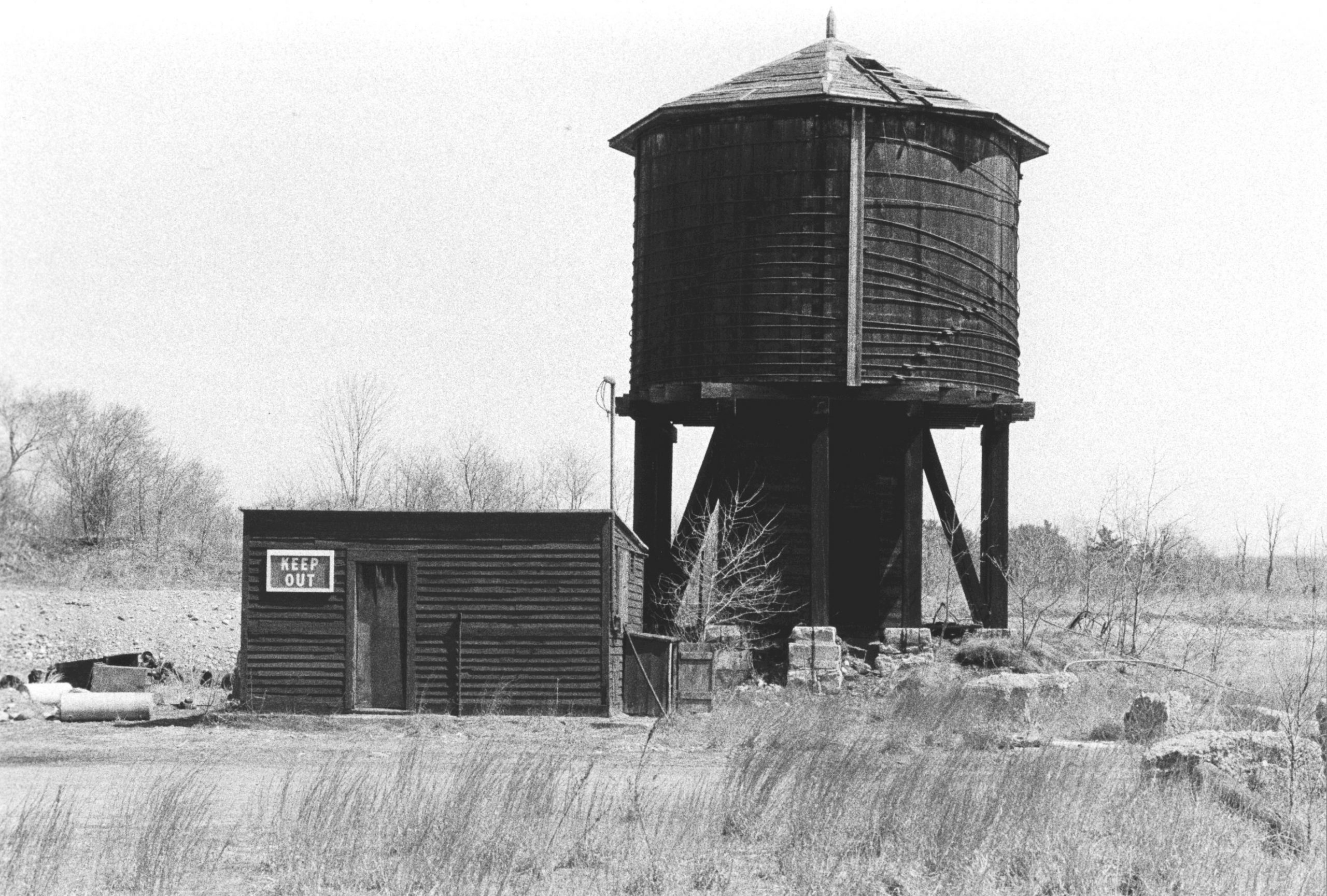

Botsford water tower, which supplied water for New Haven Railroad steam locomotives, photograph by Richard A. Fleischer, 1973

South Windham railroad station, ca. 1920s

Auto Ordnance Corporation Factory, Bostwick Avenue and Cherry Street, Bridgeport

Abandoned building

Central Avenue Interlocking Tower, Bridgeport

Interlocking tower covered with grafitti

Ives Manufacturing Corporation, Bridgeport

Abandoned factory floor covered with paper and garbage

Jenkins Brothers Manufacturing Company, Bridgeport

Exterior of abandoned building; windows boarded up, some grafitti

Penfield Reef Lighthouse, on Long Island Sound, Bridgeport

Square lighthouse on rocks surrounded by water

Stone Culvert over the Farmington Canal, Cheshire

Stone culvert

Nike Battery (missile launch site) on Country Squire Road in Cromwell/Middletown

Platform sitting int he middle of a field with overgrown buses and brush

Union Station, 120 White Street, Danbury

Abandoned railroad station with tracks in the foreground

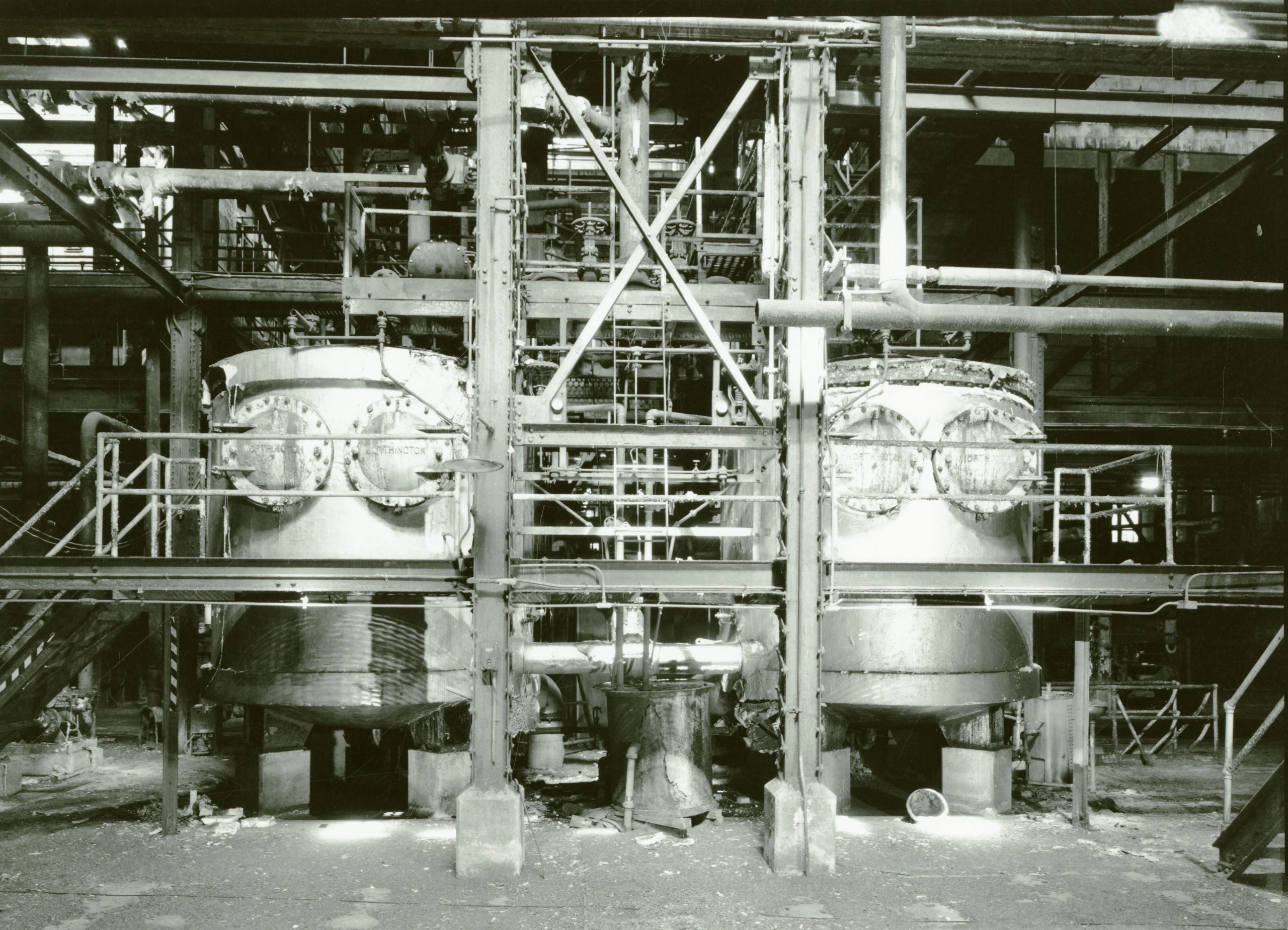

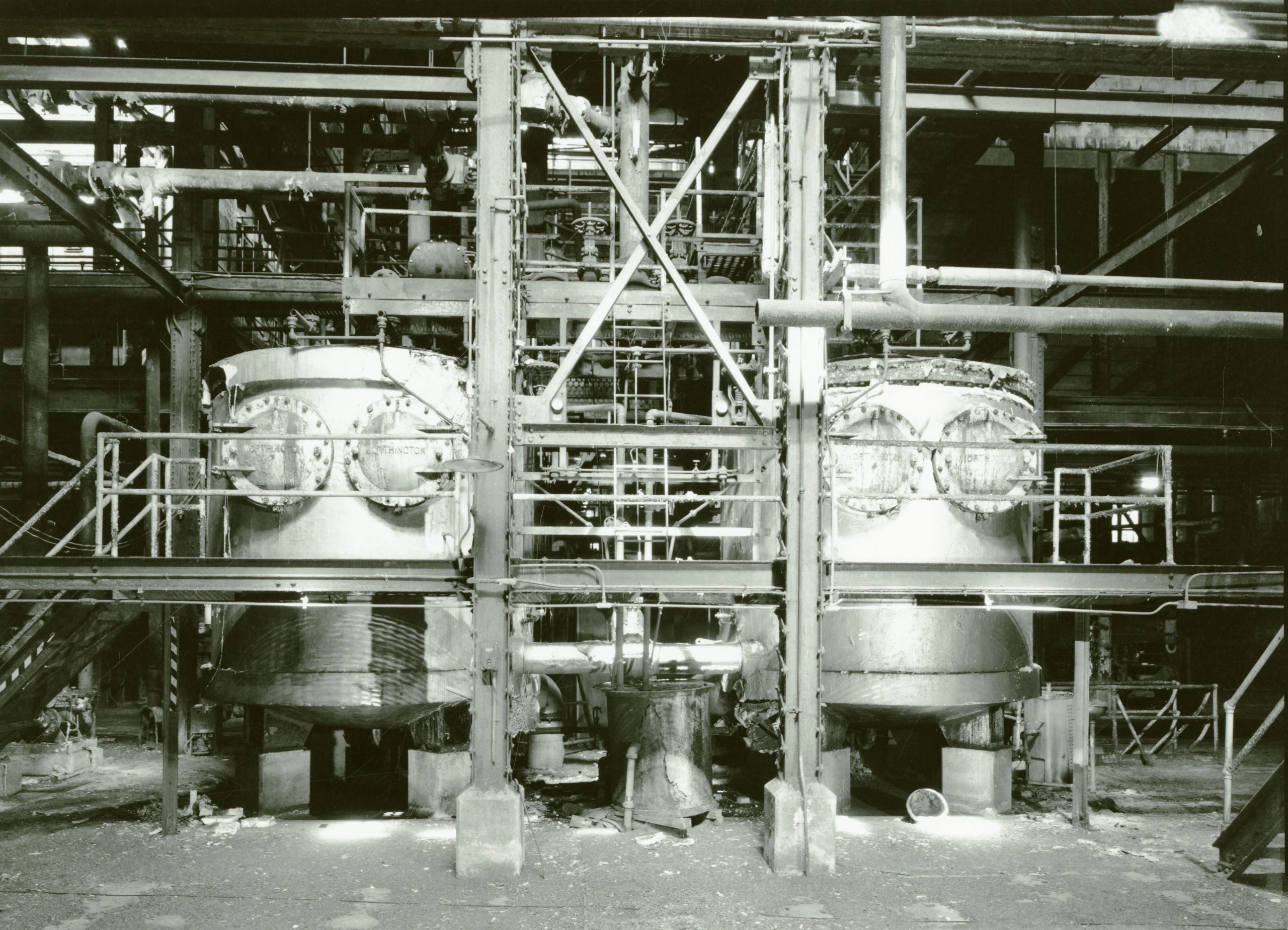

Cos Cob Power Plant, Greenwich

Two large boilers on a factory floor

Glasgo Pond Dam, Griswold

Wall of rocks on a dilapidated dam

Amtrak Groton Switch/Signal Tower, SS 119, Groton

Abandoned railroad switch tower

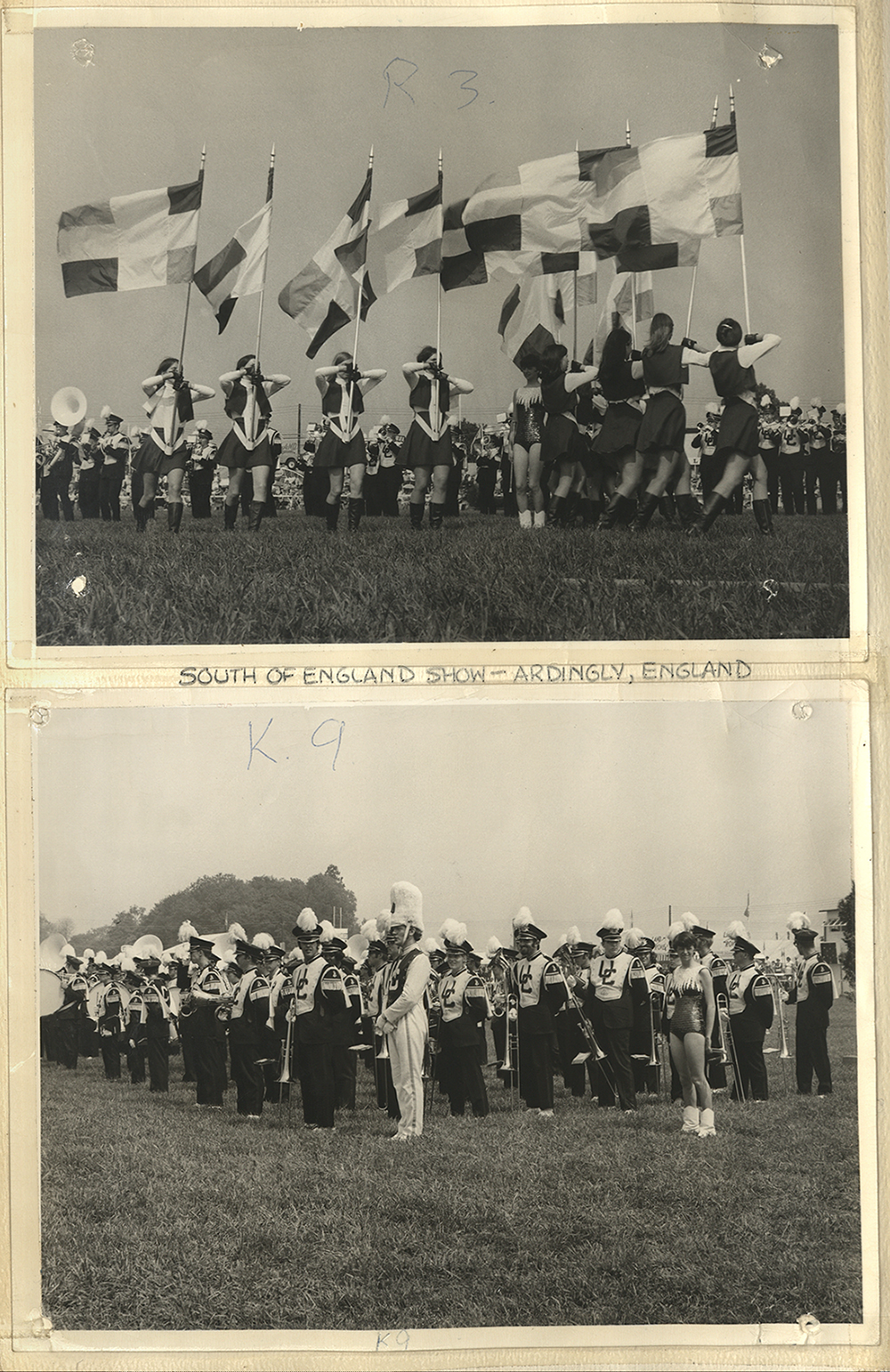

Engine House and Water Tower, 325 Old Whitfield Street, Guilford

Abandoned railroad buildings alongside tracks

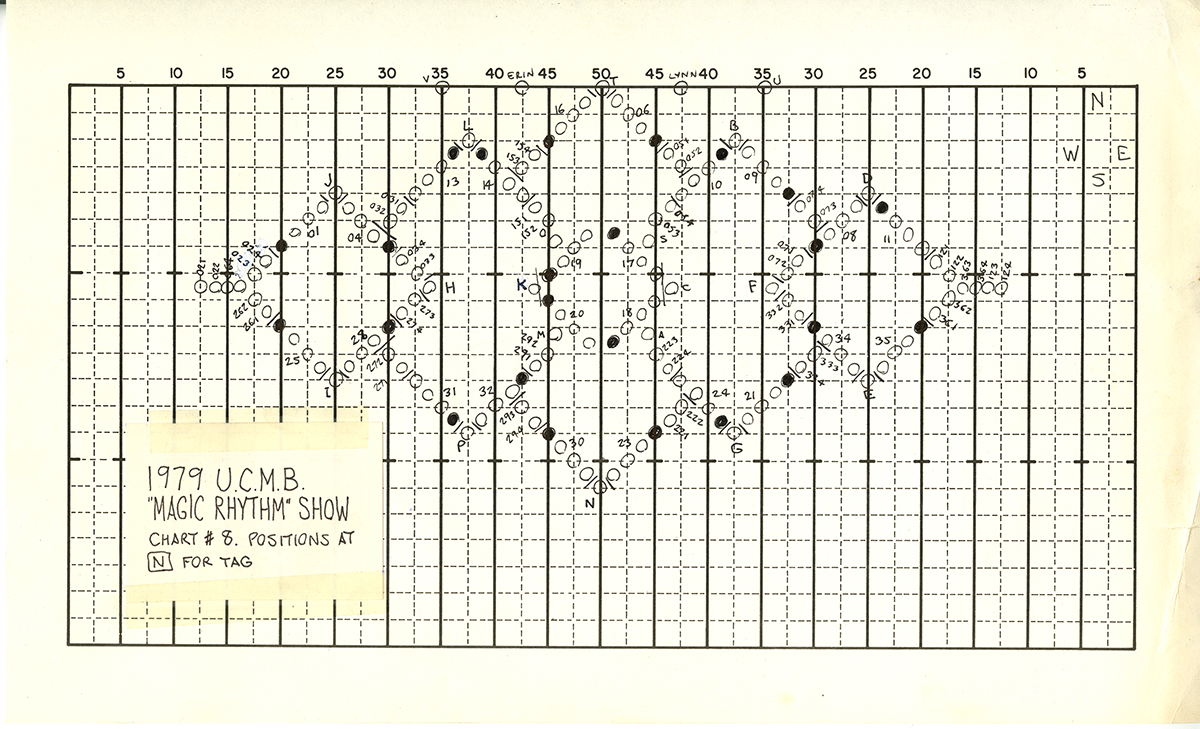

Avon Street Signal Tower, S.S. 214, Hartford

Very dilapidated abandoned railroad interlocking tower alongside tracks

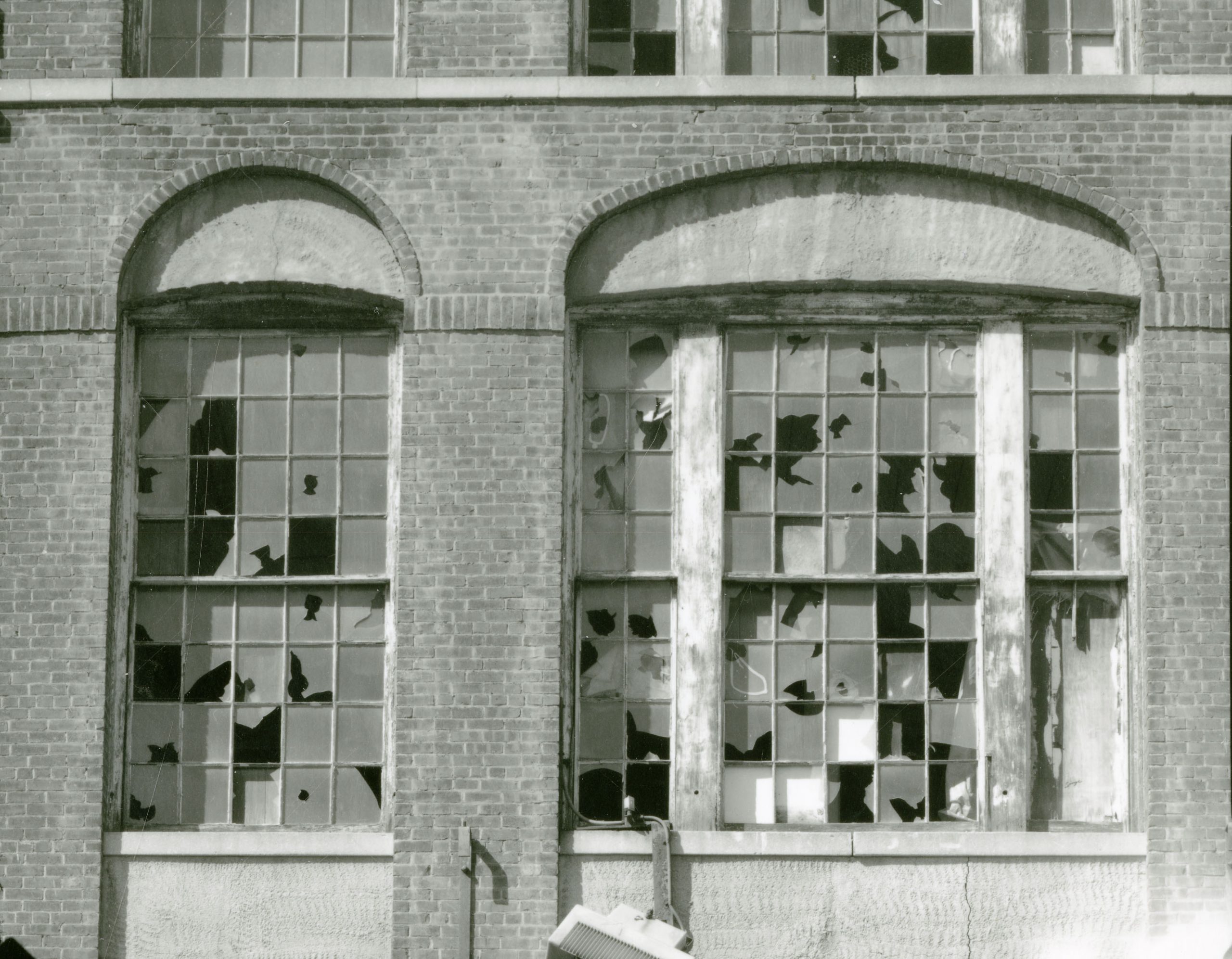

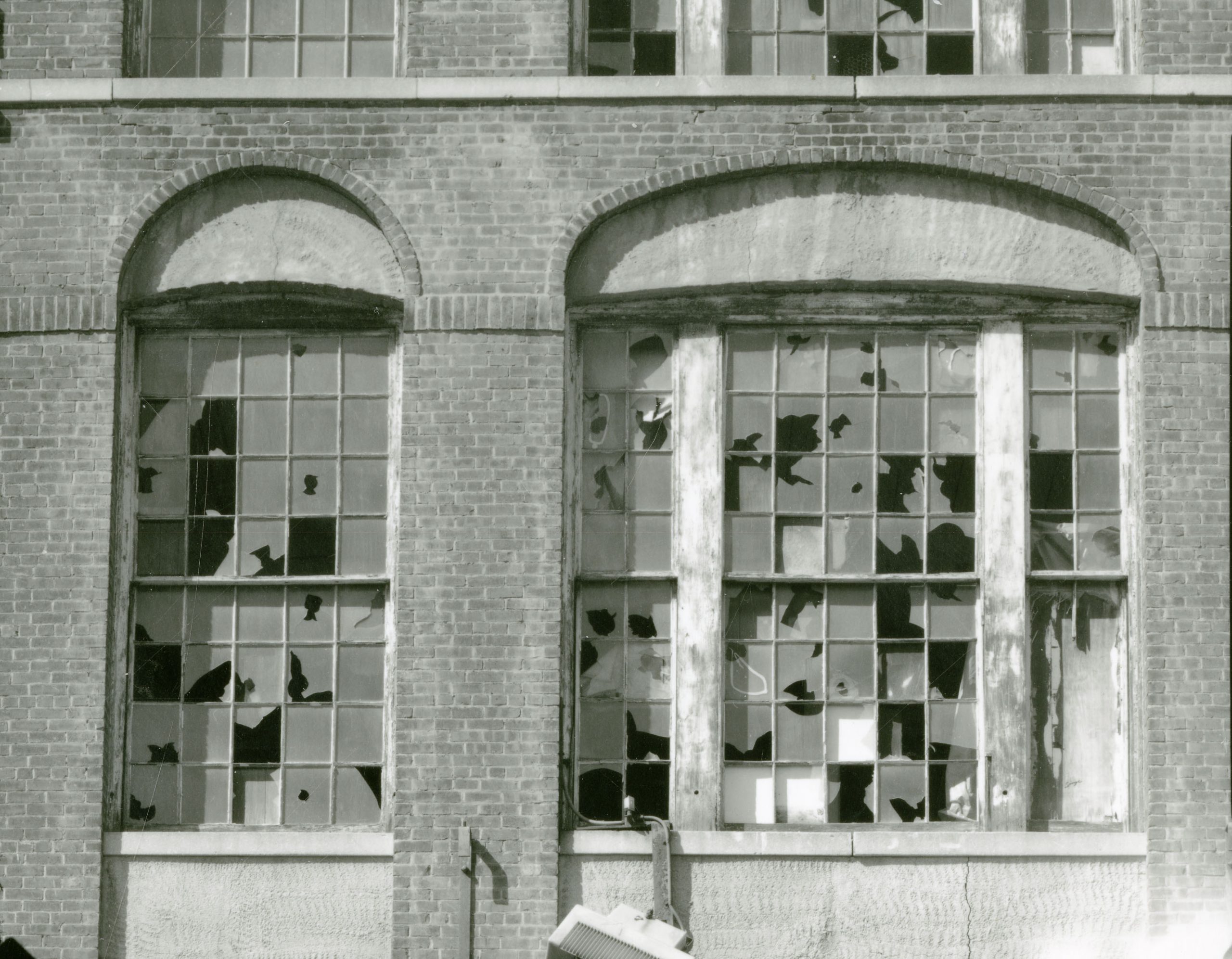

Royal Typewriter Factory, 150 New Park Avenue, Hartford

Broken windows in an old factory, exterior shot

Hartford Rubber Works, Bartholomew Avenue, Hartford

Exterior alleyway of an abandoned factory with garbage on the ground

Dairy Barn Complex, University of Connecticut, Storrs

Leaning farm building

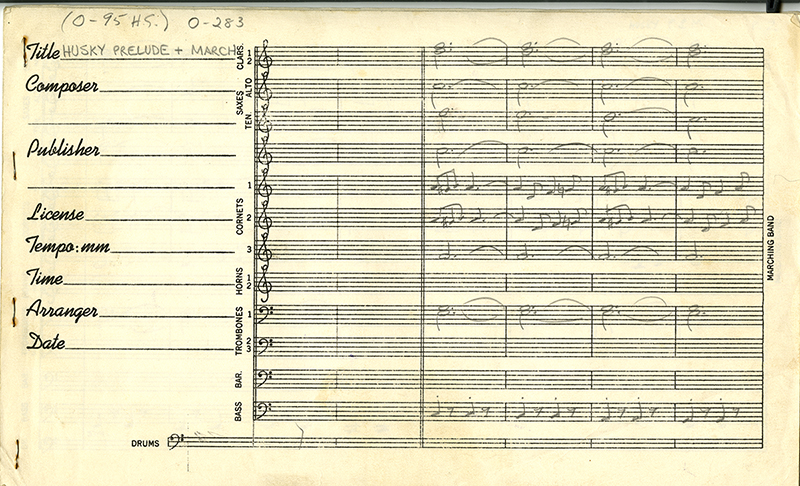

New Haven Rail Yard, New Haven

Abandoned railroad shed with broken windows

Winchester Repeating Arms Company, New Haven

Interior shot of deteriorating factory floor

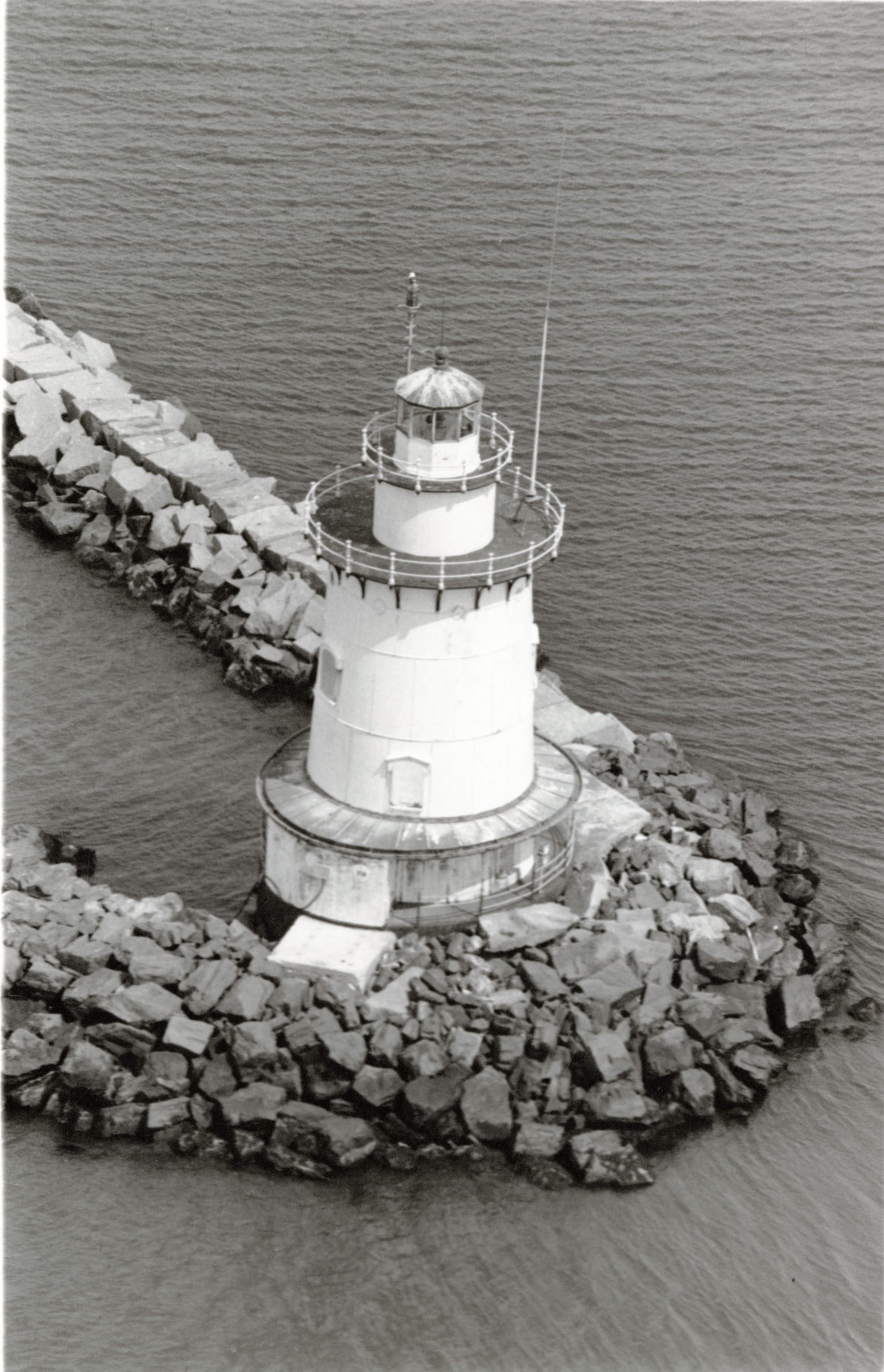

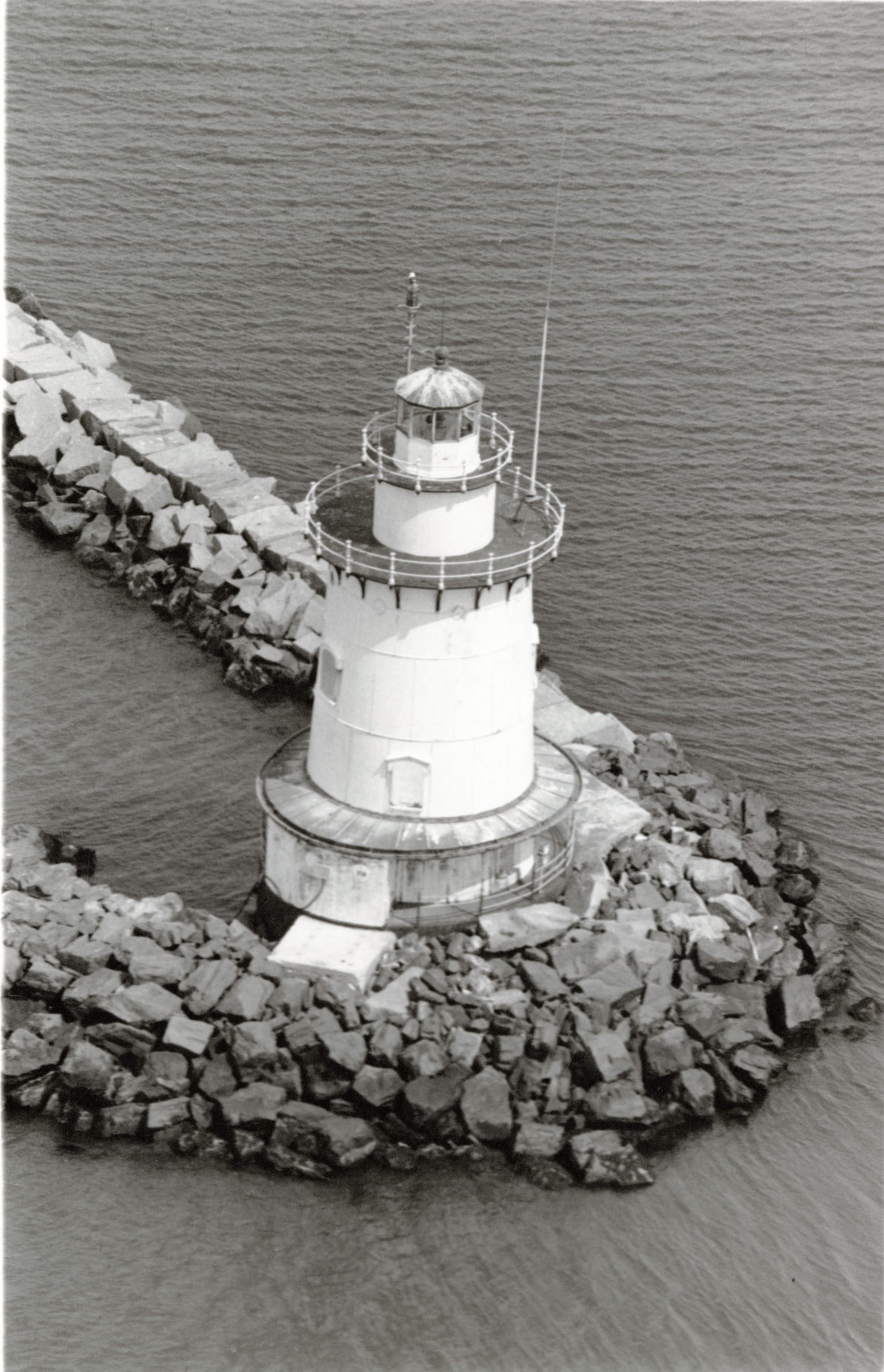

Saybrook Breakwater Light, Old Saybrook

Aerial shot of a lighhouse

South Norwalk Switch Tower 44, Washington Street, South Norwalk

Abandoned railroad interlocking tower, broken windows, grafitti

Old Saybrook Railroad Station Interlocking Tower, Old Saybrook

Abandoned railroad interlocking tower, broken and boarded up windows, next to tracks

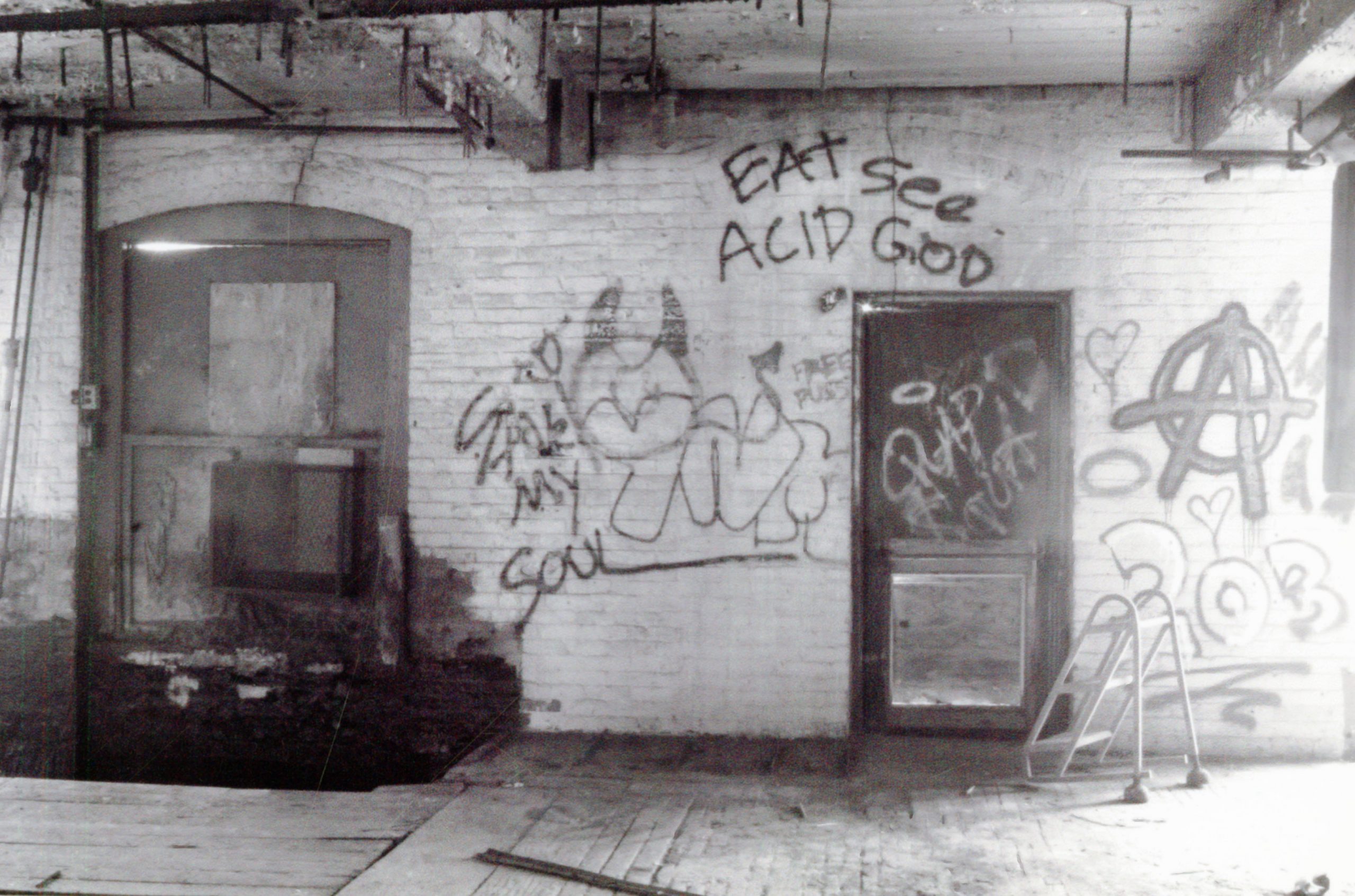

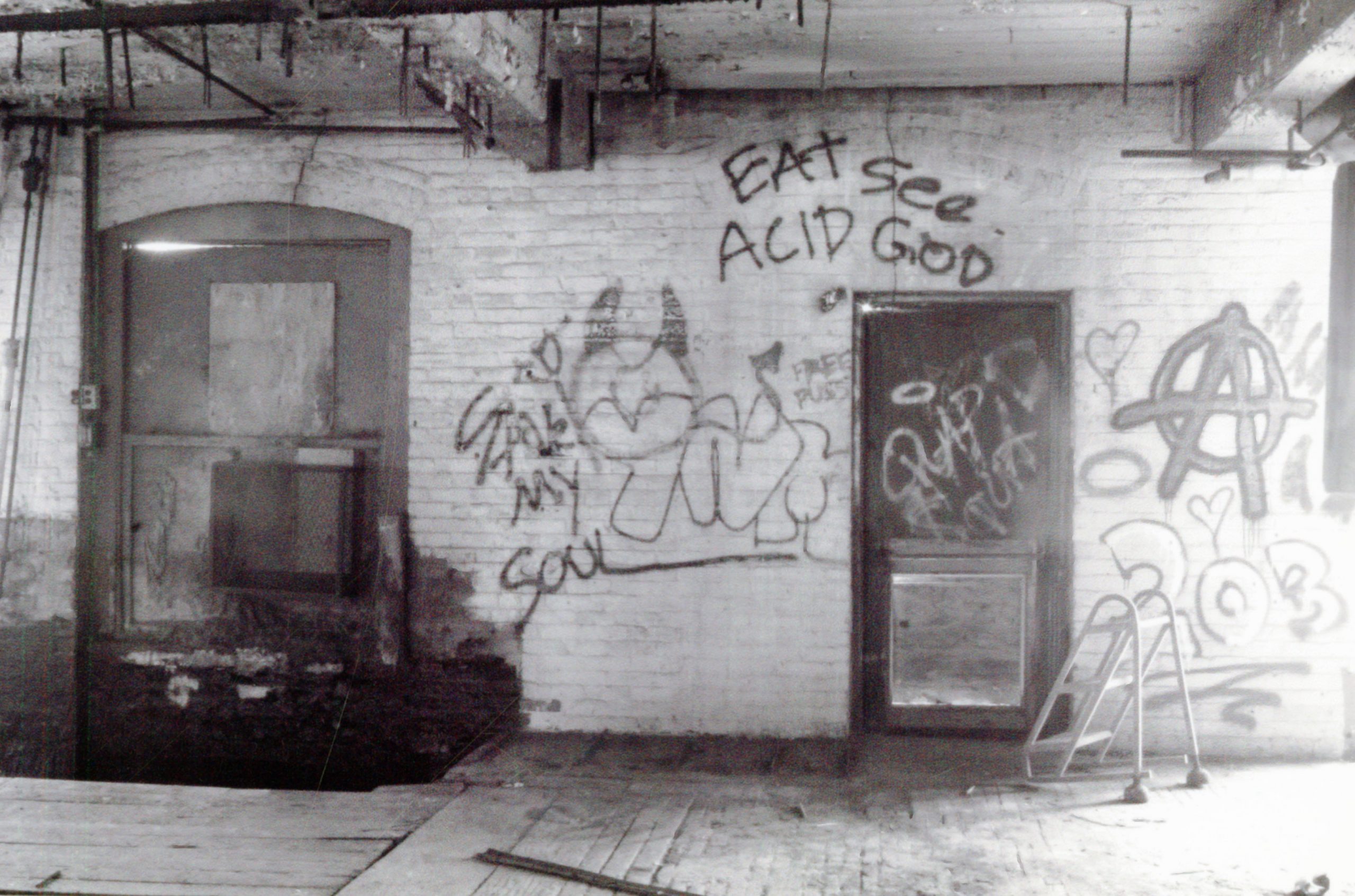

Chromium Process Company Facilities, 113 Canal Street West, Shelton

Interior of abandoned factory floor, wall covered with grafitti that reads "Eat Acid, See God"

Roosevelt Mills, Vernon

Exterior shot of factory overgrown with trees, bushes and fines. Most windows are gone.

Mattatuck Manufacturing Company, 1981 East Main Street, Waterbury

Interior shot of dilapidated, abandoned factory floor

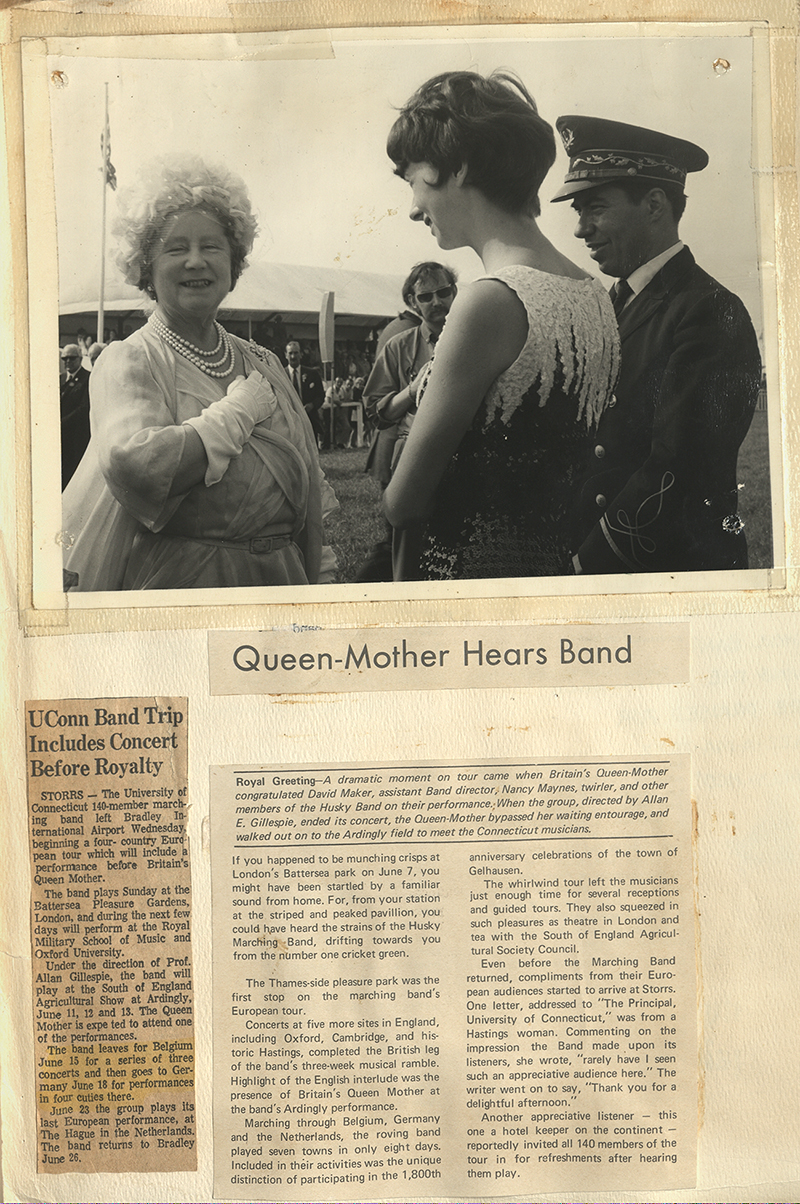

Sometimes it is hard to recall that the Connecticut of not too long ago was an industrial powerhouse. From the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s the state was a major producer of brass, tools, textiles, clocks and household goods that were valued throughout the nation, and the world. While Connecticut today is still an industrial engine, we remember a time when large factories teemed with workers and railroad lines traveled into almost every town and city in the state.

There is a mix of emotions when we view images of abandoned factories and railroad stations. There is a nostalgia for the past, one that we know through old photographs or movies, a time we somehow imagine was simpler. Or there is a curiosity in the creepy side of the structures, covered in vines, roofs sagging, broken windows, old equipment splayed about the factory floor, and, if we’re lucky, perhaps a spray of graffiti on the walls.

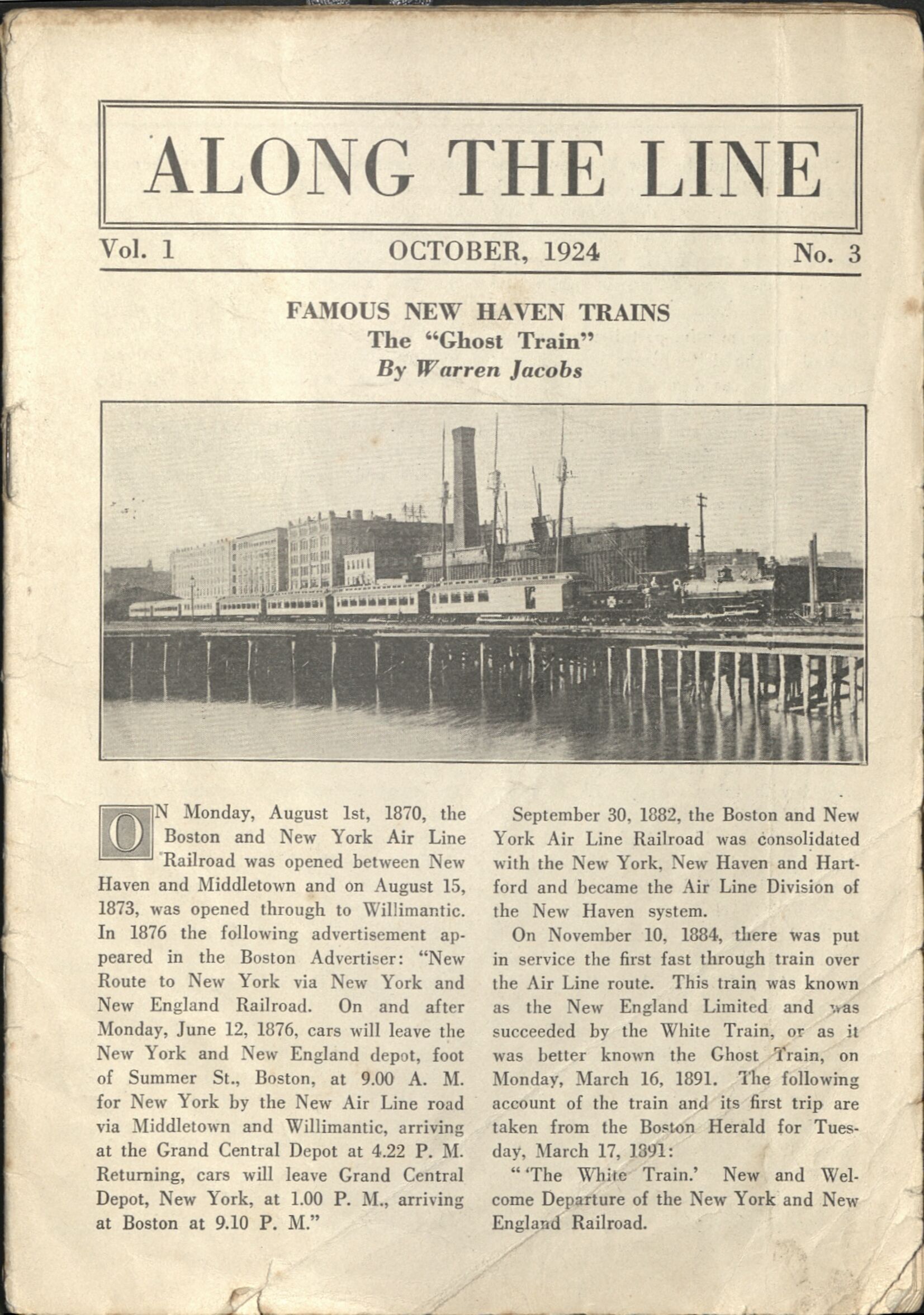

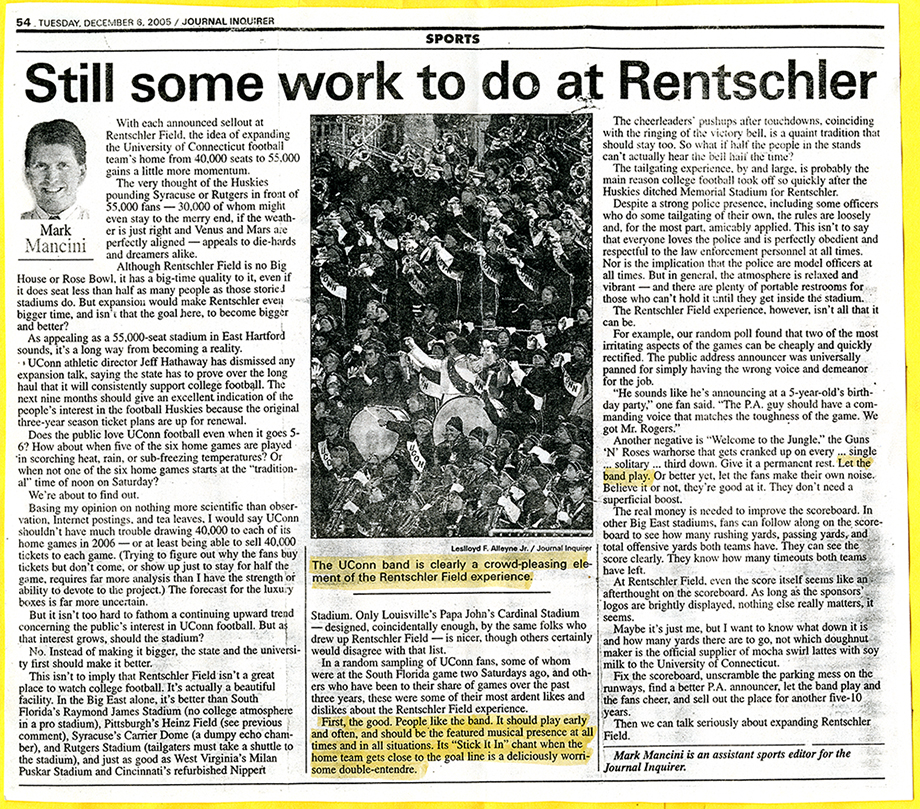

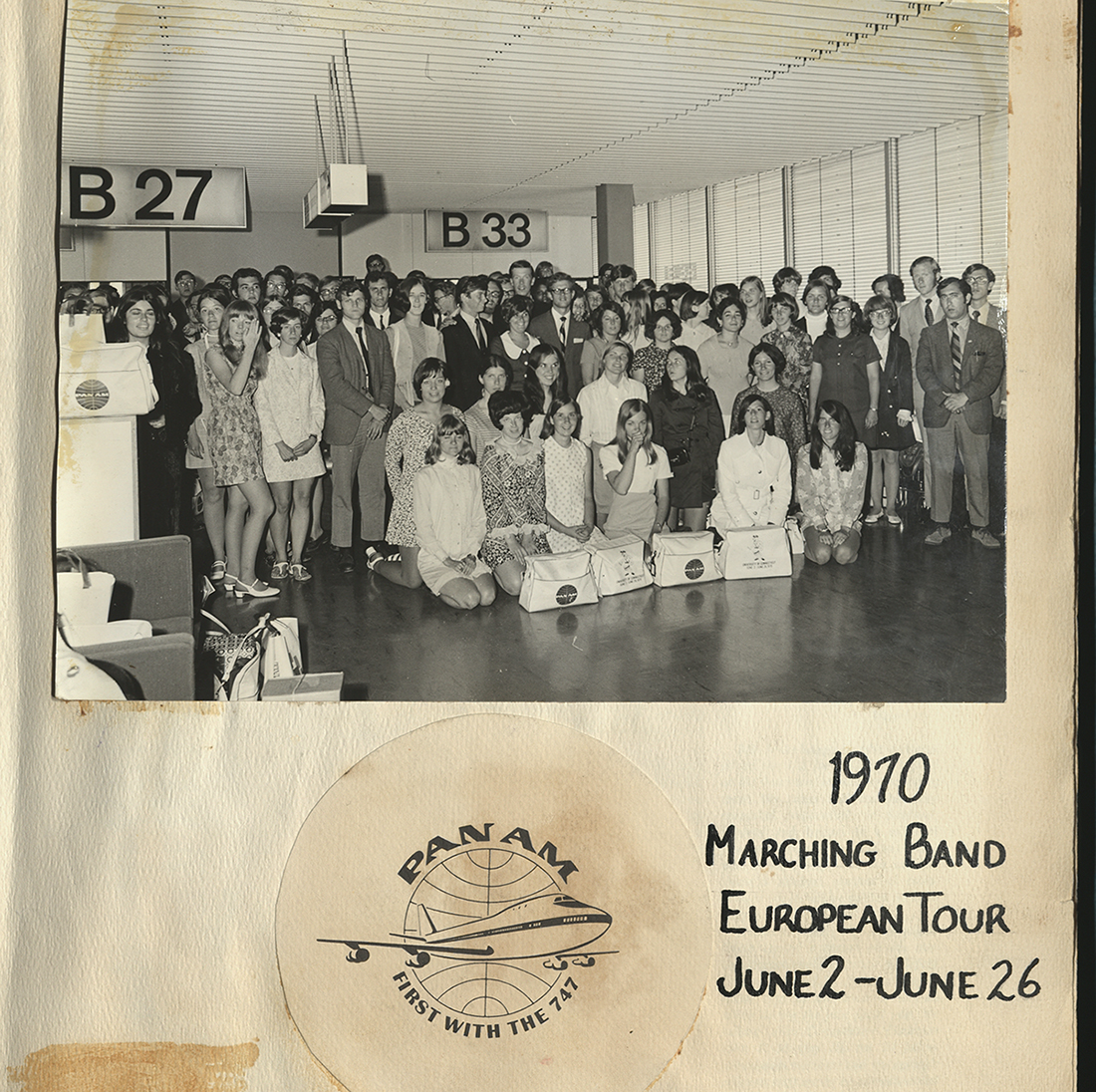

Now available in the Richard Schimmelpfeng Gallery in the Dodd Center for Human Rights is an exhibit that shows photographs from the Railroad History Collections and the Connecticut Historic Preservation Collection, both held in the UConn Archives.

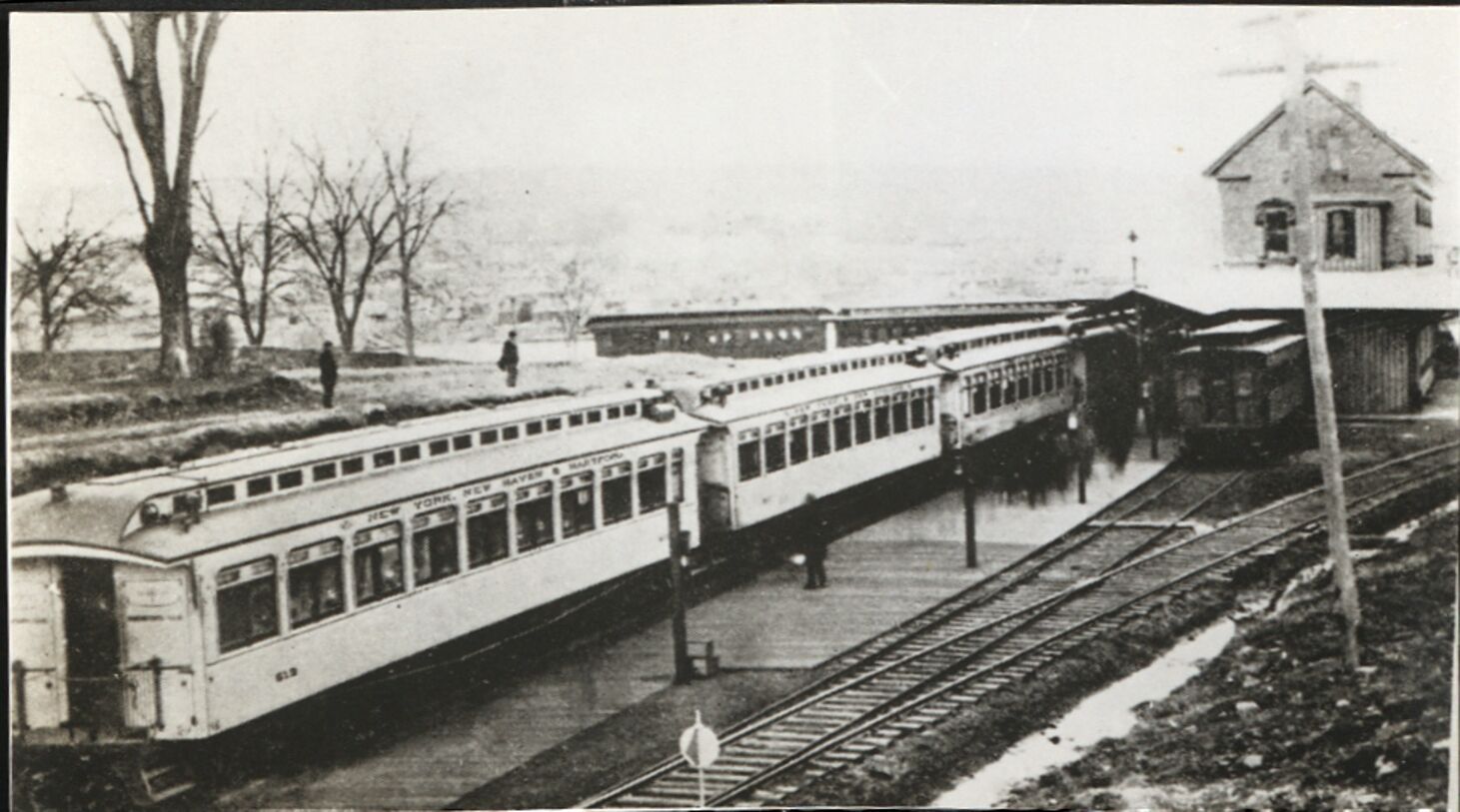

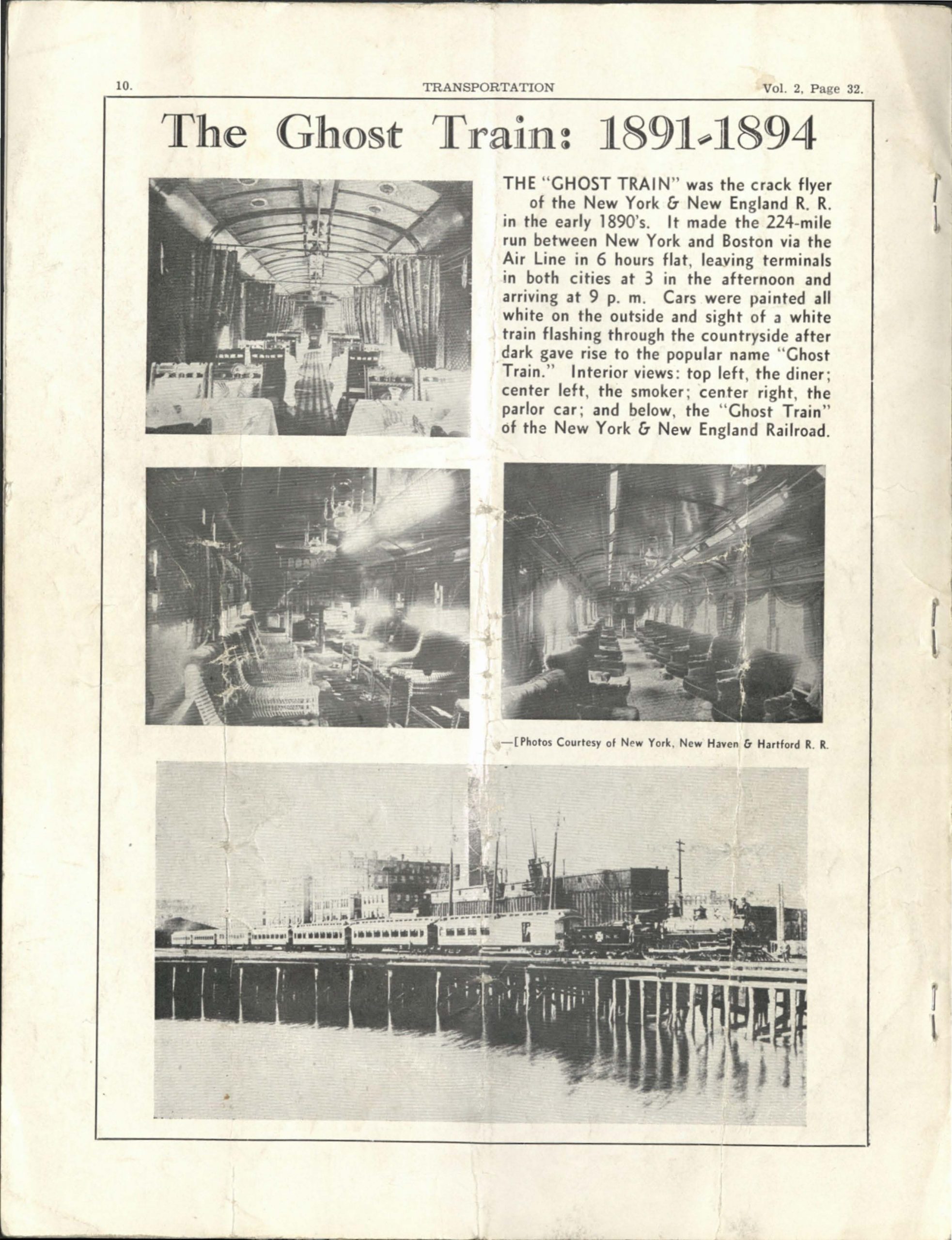

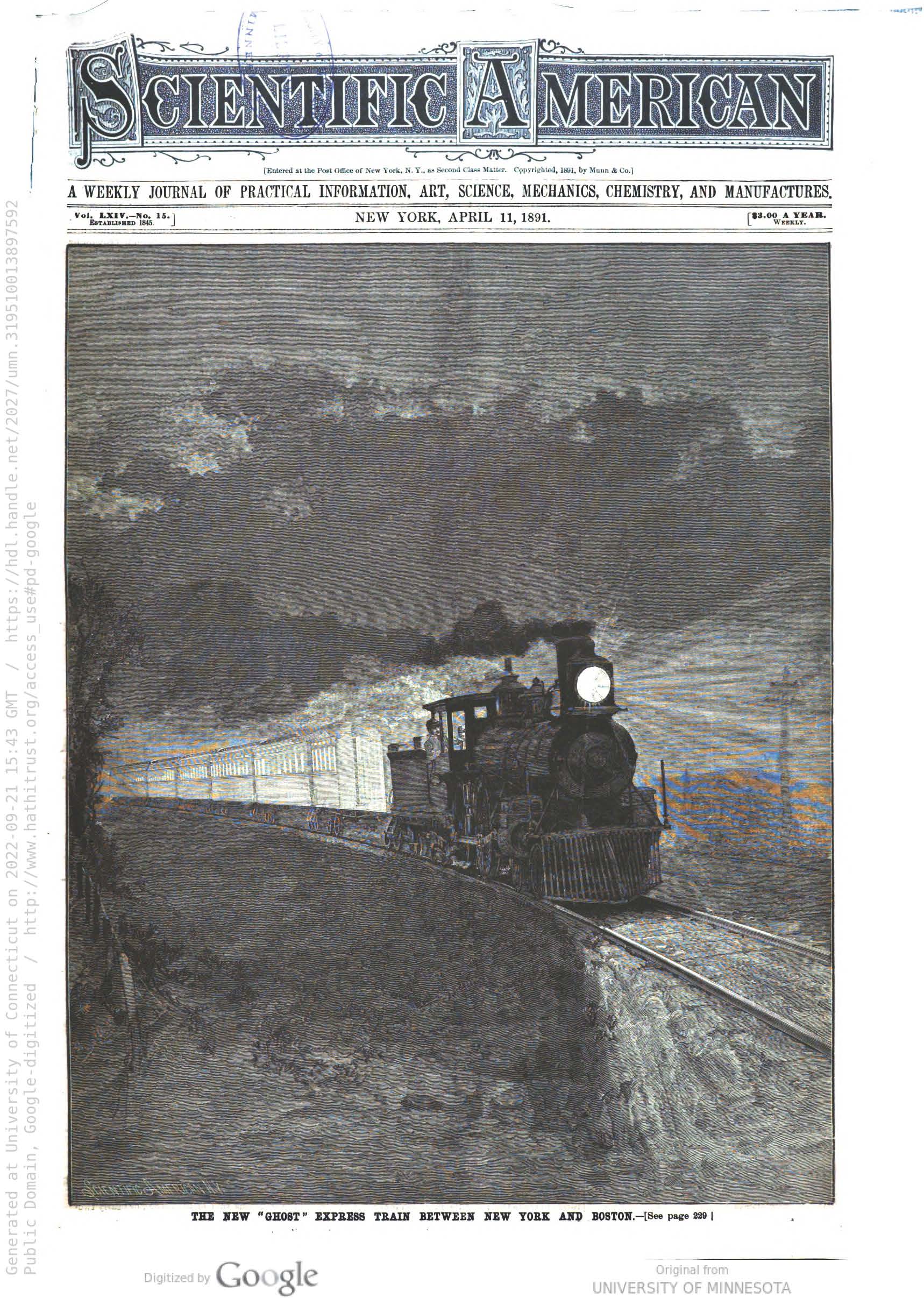

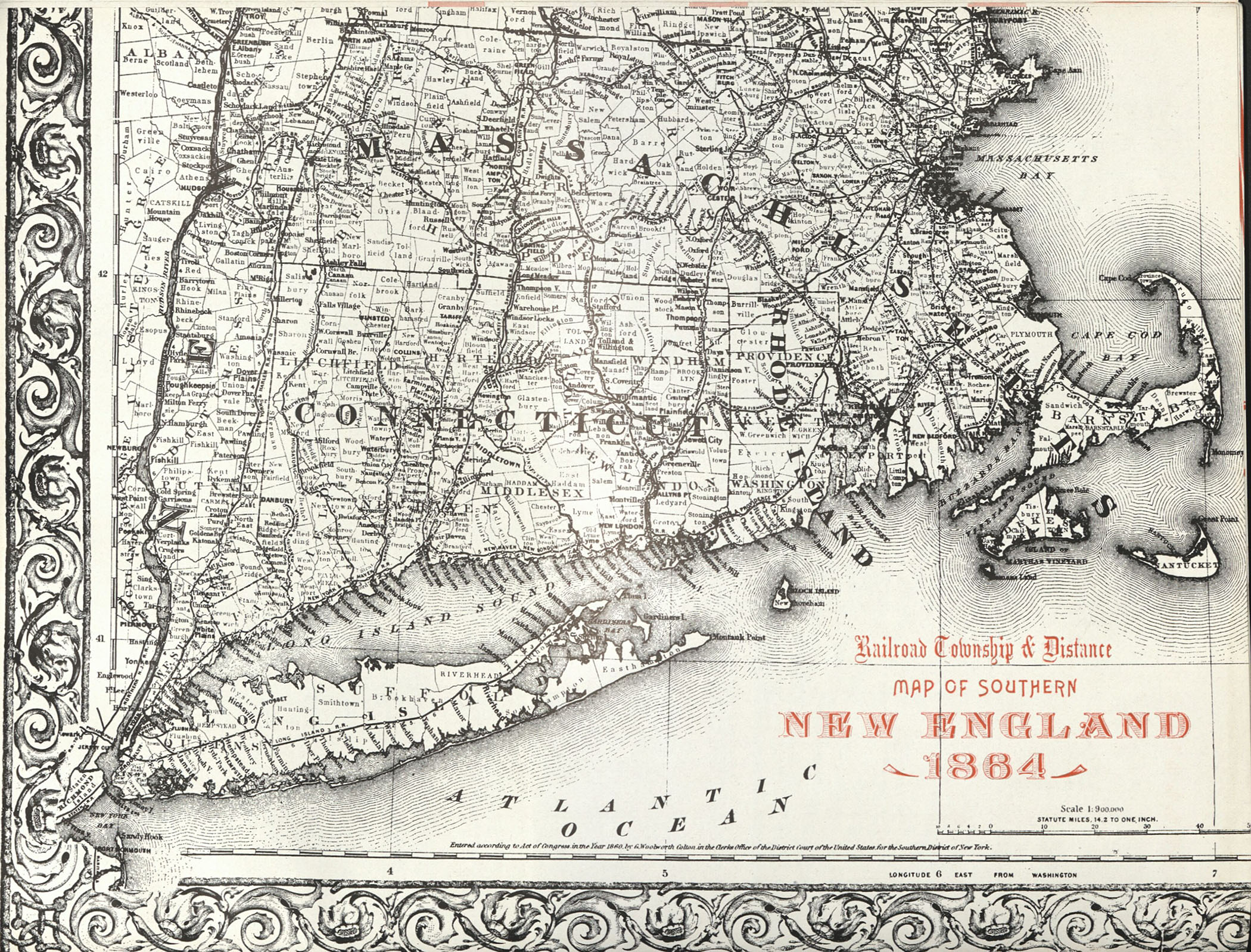

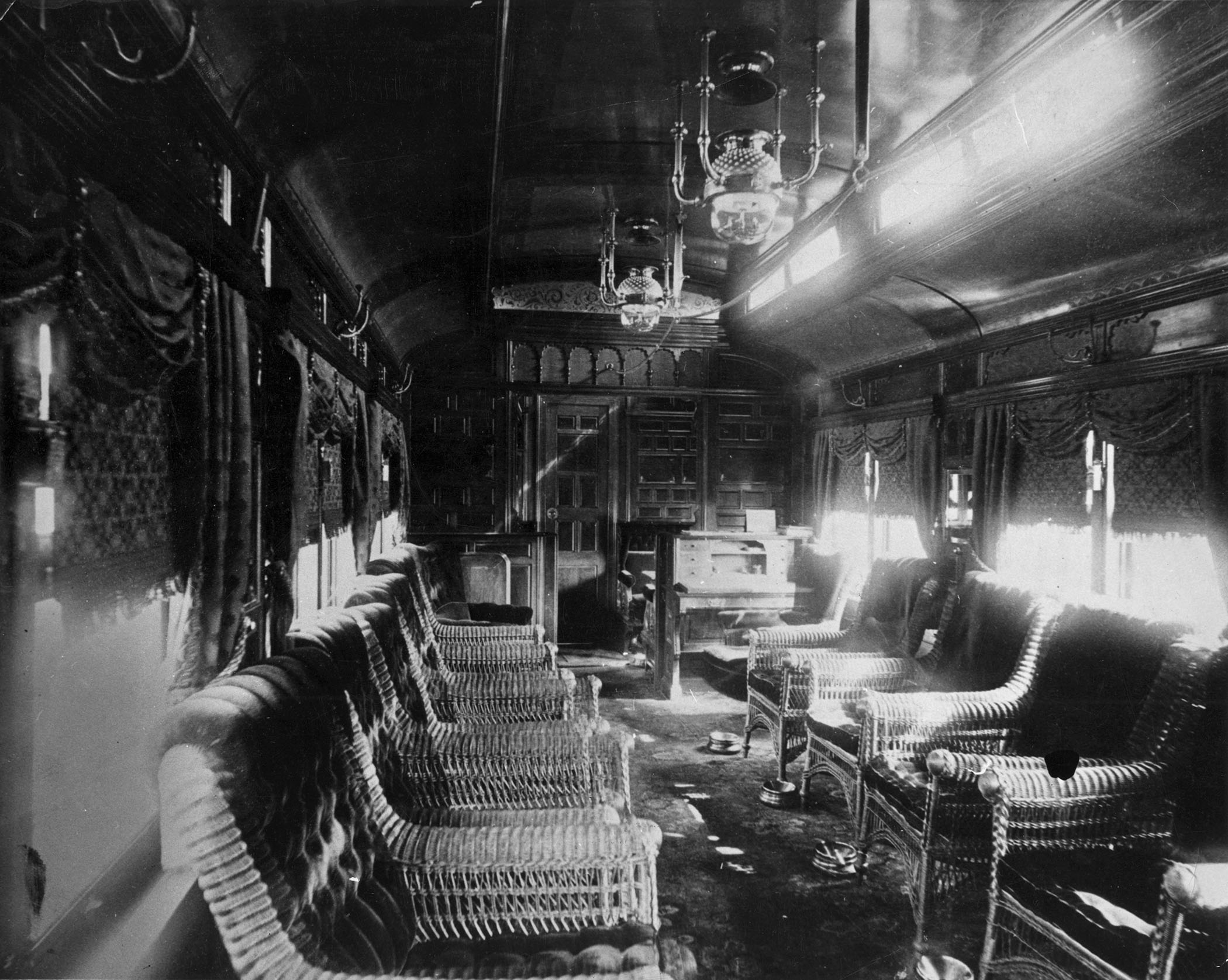

The foundational collection for the Railroad History Archives are the corporate records of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad, better known as the New Haven Railroad, which was established in 1872 from the merger of smaller lines throughout Connecticut, Rhode Island, southern Massachusetts and eastern New York, and spanned from Grand Central Terminal in New York City to Boston. Other collections, from photographers, collectors and historians, supplement the corporate records and provide resources that illustrate the impact of the railroad on the industry and culture of the region until it was absorbed into Penn Central in 1969.

While the railroad collections provide documentation on the entire New Haven Railroad region, for purposes of this exhibit we have focused exclusively on Connecticut sources.

The Connecticut Historic Preservation Collection (CHPC) is comprised of architectural and archaeological surveys, maps and documentation studies of historic buildings and sites in the state. They are provided to the UConn Archives by the State Historic Preservation Office. The CHPC materials you see in the exhibit are almost solely those in the documentation studies series, which were created by professional industrial historians to document historical properties that were planned for demolition or renovation.

The exhibit is available Mondays through Fridays, 8:00a.m. to 4:30p.m., until October 13.

Several historians have graciously aided us with this exhibit, by either providing their advice or expertise of railroad properties, or by allowing the use of photographs they have taken of abandoned sites.

Robert Joseph Belletzkie has done extensive research into the history of Connecticut railroad stations. He created and maintains a website – Tyler City Station, at http://www.tylercitystation.info/ — that details the history of virtually every station and depot in Connecticut.

Matthew Chase is dedicated to a project to document the deterioration of the Cedar Hill Rail Yard, located in New Haven. His Facebook page, Friends of Cedar Hill Yard, has hundreds of photographs of the yard, both historical and in its deteriorating condition in the present day.

Richard A. Fleischer is a historian, writer and photographer with a broad and deep knowledge of the history of New England’s railroads.

J.W. Swanberg is a former railroad employee, photographer and historian of the New Haven Railroad, with a lifetime of knowledge about railroads in Connecticut, the region and the world. He is the author of the seminal history of the New Haven Railroad’s locomotive fleet, New Haven Power, and has written extensively on topics related to railroads in the region.