The following guest blog post is by Daniel Allie, a 2014 graduate of the University of Connecticut’s English Program. While a student, Mr. Allie worked in Archives and Special Collections for two years as a Student Library Assistant. Since graduation, he has turned to the field of History, and volunteers his time at the Mansfield Historical Society and the Connecticut Historical Society as well as researching and writing pieces like this one for Archives and Special Collections.

What can a book tell you?

Quite a lot, though not necessarily in the way you would immediately suppose. You can read the text, certainly, but sometimes minor annotations to a volume tell a more compelling story than that.

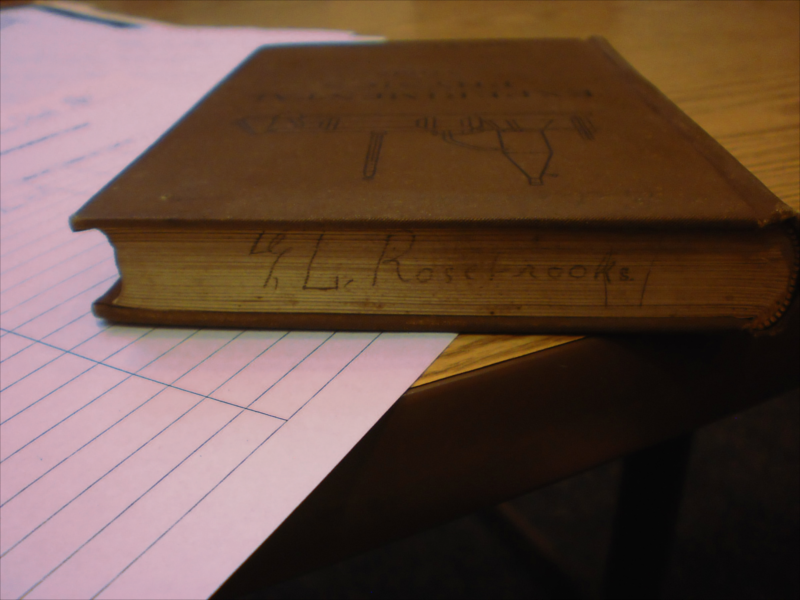

This is the case for a collection of late nineteenth and early twentieth century textbooks recently donated to Archives and Special Collections. By most estimations, this is dry stuff—titles include Milk and its Products; Elements of Chemistry; and The Beginner’s American History among others—but it was not this specific content that is what is most interesting. The true story lies with the annotations within these volumes, a story of the early University of Connecticut and the surrounding community of Mansfield.

The annotations within the books indicate two separate collections, those of George L. Rosebrooks and of Harold L. Storrs, respectively. It is clear from name alone that Harold L. Storrs is part of the family that founded the University, though this does not necessarily indicate a connection, and is unrelated to what we can learn from his books. We can immediately tell from the books that Harold L. Storrs was likely a generation younger than George L. Rosebrooks, as his books were later-published texts for younger students. While Rosebrooks owned Elements of Chemistry (1881), Storrs owned The Beginner’s American History (1902). I was able to confirm this in a genealogical record of the Storrs family, which indicated that Harold L. Storrs was born on October 2, 18951, while the Commemorative Biographical Record of Tolland and Windham Counties confirms that George L. Rosebrooks was born September 21, 18792. A document in Archives and Special Collections indicates that Storrs was an employee of the university in 19313.

As interesting as it is to learn that Harold L. Storrs was a university employee, though, the books from the Rosebrooks family provide a more compelling story. At the beginning of the project, we knew from the donor of the collection that George L. Rosebrooks was an 1899 graduate of Storrs Agricultural College, and we knew that George L. Rosebrooks’s brother Fred Rosebrooks (also a Storrs Agricultural College graduate) ran the Mansfield, Connecticut poor house.

Knowing that the Rosebrooks family was related both to the early university as well as the Mansfield Poor House raised questions worth investigating about the collection: Could any of these volumes be related to George L. Rosebrooks’s education at the Storrs Agricultural College? Are any of the other volumes in the collection from the the poor house, books meant for the education of resident children?

To answer the latter question, some of the books in the collection which are signed by neither George L. Rosebrooks nor Harold L. Storrs, are in fact didactic texts, earlier dated schoolroom readers such as An Introduction to the Study of English Grammar (1856) and Hillard’s The Sixth Reader (1866). Since these books were not directly connected to any Rosebrooks family member, it seemed possible that they had come from a potential Poor House library.

I was able to further confirm this as a possibility at the Mansfield Historical Society. The book The Mansfield Poor House: A Forgotten Institution includes a transcription of the House’s founding document, which reads, in part: “the said Barrows [founder of the Poor House] further agrees to send all children of a suitable age to school and to furnish them with suitable books”4, thus establishing Poor House provenance as possible, though I would caution that the fact that the books could possibly have been part of the Poor House’s collection is by no means a confirmation that this is true for these specific examples. Any schoolchild of the time could have possessed them.

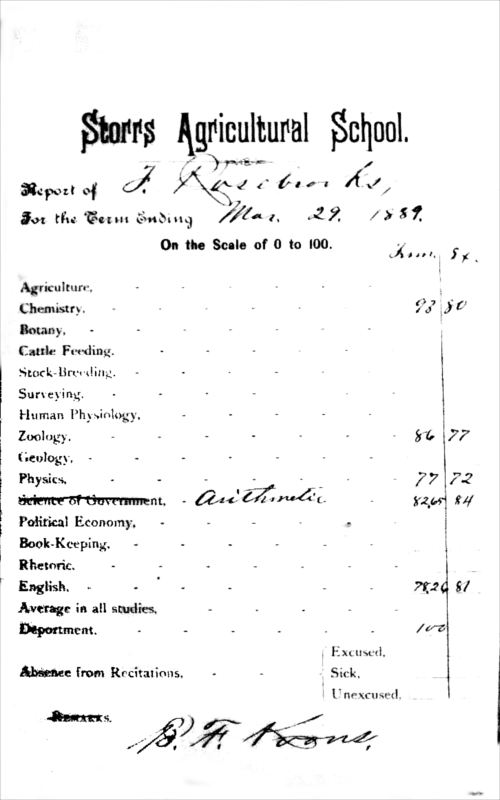

Far more certain, though, is the books’ connection to the Storrs Agricultural College. Already well documented is the Rosebrooks family’s relation to the early university, a fact attested by an item from the Mansfield Historical Society, Fred Rosebrooks’s report cards. The Ethel Larkin Papers, comprising documents collected by a late Historical Society member, contains the student records of Fred Rosebrooks. Dated to 1888 (a decade earlier than his brother George’s textbooks), these records show Fred Rosebrooks taking such courses as Chemistry, Arithmetic, Physics, and English, out of a possible fifteen subjects offered on the report card at that time5.

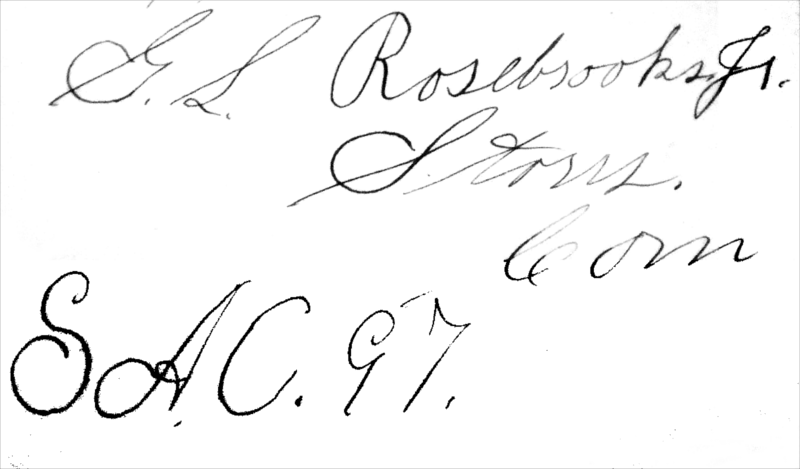

With the Rosebrooks family’s connection to the early university already clearly established, it is unsurprising to find that the new collection’s copy of Elements of Chemistry by Elroy M. Avery includes an annotation inside the cover reading “G.L. Rosebrooks Jr., Storrs, Conn. SAC [Storrs Agricultural College]. 97.,” indicating that Rosebrooks had this book for one of his college courses. The Connecticut College of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts Catalogue 1899-1900 partially confirms this, albeit with a different book of the same title. The description of their course in “General Chemistry” has as its text “Williams’ Elements of Chemistry”6.

George L. Rosebrooks’s signature, accompanied by the annotations ‘Storrs, Conn’ and ‘SAC. 97’, in Elements of Chemistry.

The coursebook connection is even clearer in the case of the book Milk and its Products. The description of the course “Dairying” in the Storrs Agricultural College Catalogue: 1898-1899, reads “A short winter course in dairying. . . including composition of milk, conditions of creaming, milking for market, butter making, washing, salting, packing, etc. Breeding, feeding, and diseases of dairy cattle are subjects also treated in this course, with such texts as ‘ Milk and its Products,’ ‘ Bacteriology,’ and ‘Feeds and Feeding’”7, thus confirming the actual use of one of the books owned by George L. Rosebrooks in a Storrs Agricultural College course.

So those are a few things a book can tell you. Individually, these texts would perhaps have said little beyond their original subjects. Together, they form a context with each other, through their original owners, illustrating a history, be it local, academic, or familial. What one will find when conducting historical research is never certain, but in searching through the collections of two institutions, the University of Connecticut Archives and Special Collections as well as the Mansfield Historical Society in the search for this collection’s history and significance, I found far more significance to this collection than one would ever expect to find from a collection of century-old textbooks and readers.

-Daniel Allie

1 Durand, Robert. Storrs Family Pedigree Chart. Mansfield Historical Society digital record. Accessed 13 July 2016.

2 “George L. Rosebrooks.” In Commemorative Biographical Record of Tolland and Windham Counties. (Chicago: J.H. Beers & Co, 1903), 420.

3 “Financial Summary: Farm Receipts: Poultry, 1931.” University of Connecticut Agricultural Economics Records, Series VII, Subseries B, Box 42. University of Connecticut Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center.

4 “Contracts.” In The Mansfield Poor House: A Forgotten Institution. (Mansfield: History Workshop of The Mansfield Historical Society, 1985), 7.

5 “Storrs Agricultural School: Report of F. Rosebrooks, For the Term Ending Mar. 29, 1889.” Ethel Larkin Papers, Mansfield Historical Society, Mansfield, Connecticut.

6 Connecticut College of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts Catalogue 1899-1900, 25. University of Connecticut Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center.

7 Storrs Agricultural College Catalogue: 1898-1899, 13. University of Connecticut Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center.

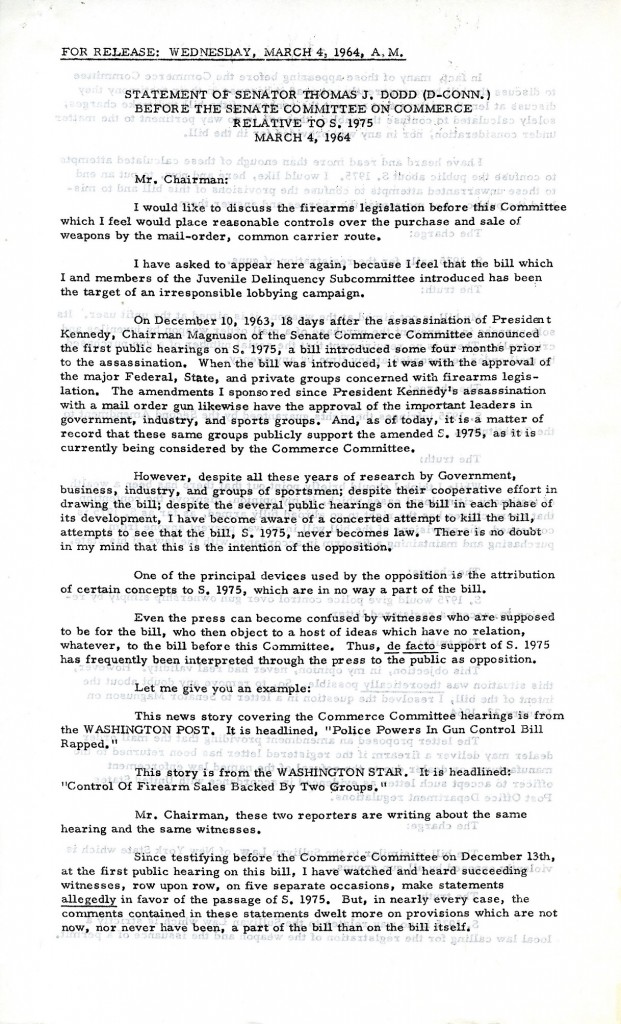

Kennedy.

Kennedy.