[slideshow_deploy id=’9195′]

On April 26, 1962, Edwin Way Teale, at Trail Wood, his home in Hampton, Connecticut, wrote this passage:

A little after 5 am, just as the sun was rising above the trees along the brook, this morning, I walk down Veery Lane, up over the tundra and to Juniper Hill the long way. The air – down to 35 [degrees] — has an autumn sparkle. I see the earliest tent caterpillar nests shining silver in the crotch of a wild cherry sapling. All the ravines are filled with the yellow-green stippling of the spicebush blooms. Where a maple has fallen across the path near the crossing before Juniper Hill, I see where some animal has gnawed the bark from several branches near the ground. What was it – a rabbit? Because only the lower and smaller branches were attacked a rabbit seems to be the most likely possibility rather than a deer or porcupine…

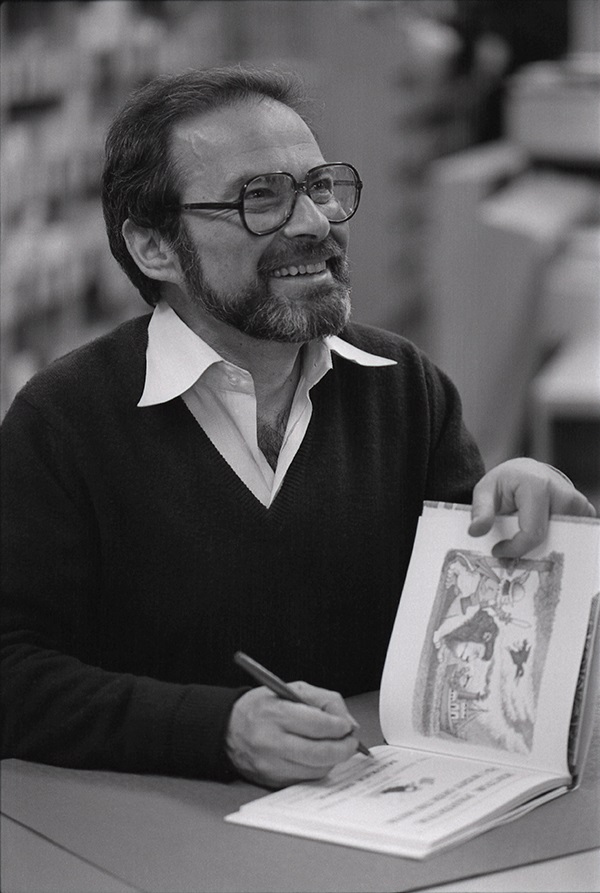

Edwin Way Teale (1899-1980) was a naturalist, photographer and writer, born in the Midwest but who lived in New York after earning his masters degree at Columbia University. In the 1930s he worked as a writer and photographer for the magazine Popular Science and began his career as the author over 30 books on natural history topics. His books include Dune Boy: The Early Years of a Naturalist (1943), The Lost Woods (1945), North With the Spring (1951), Journey into Summer (1960), and Wandering Through Winter (1965), for which he won the 1966 Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction.

In 1959 Teale and his wife Nellie left suburban Long Island for 130 acres of farmland in Hampton. They named the property Trail Wood and developed a series of looping trails, which the Teales walked almost daily. He describes the property in such books as A Naturalist Buys an Old Farm (1974) and A Walk Through the Year (1978).

A constant writer, for much of his life Teale kept a daily journal with the details of his habits and musings. He also kept a special journal – The Trail Wood Journal – about his observations of the change of seasons of the landscape of his beloved patch of land.

Fifty-eight years after Teale wrote the journal entry noted above, the author of this blog post visited Trail Wood, which is now managed as a nature preserve by the Connecticut Audubon Society and open to the public. It is my impression that the landscape I walked on my visit on April 25, 2020, was fairly close to that of which Teale wrote about on April 26, 1962, excepting the existence of trail signs installed along the way for visitors. The streams of this mid-Spring were running freely, the day was warm and the bugs abuzz. While I cannot claim to be as observant a nature lover or as skilled a writer as Edwin Way Teale, I can claim the same joy he must have felt whenever he strode the trails, discovering whatever revealed itself to him.

Archives & Special Collections holds Edwin Way Teale’s extensive papers and photographs, truly one of our premier collections. Some of the photographs, as well as Trail Wood Journal, can be found online in our digital repository.

The finding aid to the Edwin Way Teale Papers is at https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/788

Trail Wood Journal, in our digital repository: http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:860204261

Photographs of and by Teale photos in digital repository: http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:MSS19810009

In late 2016 and the first half of 2017 author Richard Telford spent many months intensively researching the Teale collection in preparation for a book he was writing on Teale’s life. Mr. Telford contributed many posts to our blog, which are drafts from the book. In them the details of Teale’s life, as revealed in the diaries, correspondence and publications, are beautifully placed into context. You can find Telford’s writings, which he titled Reexamining the Life and Writing of Edwin Way Teale in our blog:

Great Years, Great Crises, Great Impact, November 2016: https://blogs.lib.uconn.edu/archives/2016/11/30/great-years-great-crises-great-impact-reexamining-the-life-and-writing-of-edwin-way-teale/

The Lonely Suffering of the Fallible Heart, January 2017: https://blogs.lib.uconn.edu/archives/2017/01/12/the-lonely-suffering-of-the-fallible-heart-reexamining-the-life-and-writing-of-edwin-way-teale/

Throwing Bricks at the Temple, February 2017: https://blogs.lib.uconn.edu/archives/2017/02/14/throwing-bricks-at-the-temple-reexamining-the-life-and-writing-of-edwin-way-teale/

Losing the Remembrance of Former Things, March 2017: https://blogs.lib.uconn.edu/archives/2017/03/16/losing-the-remembrance-of-former-things-reexamining-the-life-and-writing-of-edwin-way-teale/

Into the Beautiful, Free Country, May 2017: https://blogs.lib.uconn.edu/archives/2017/05/25/prologue-into-the-beautiful-free-country-reexamining-the-life-and-writing-of-edwin-way-teale/

Chasing the Erratic Spotlight of Memory, June 2017: https://blogs.lib.uconn.edu/archives/2017/06/29/chasing-the-erratic-spotlight-of-memory-reexamining-the-life-and-writing-of-edwin-way-teale/

Nobody and Somebody: The Loving Ways of Lone Oak, August 2017: https://blogs.lib.uconn.edu/archives/2017/08/24/nobody-and-somebody-the-loving-ways-of-lone-oak-reexamining-the-life-and-writing-of-edwin-way-teale/

The Connecticut Audubon Society, which maintains Trail Wood, has information about Edwin Way and Nellie Teale online and on the signs throughout the trails. Happily most of the boards are reproduced on their website. You can find this information at these links:

Trail Wood website: https://www.ctaudubon.org/trail-wood-home/

Trail Wood signs: https://www.ctaudubon.org/trail-wood-the-teales-legacy/

Teale bio: https://www.ctaudubon.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/tealebio1.pdf