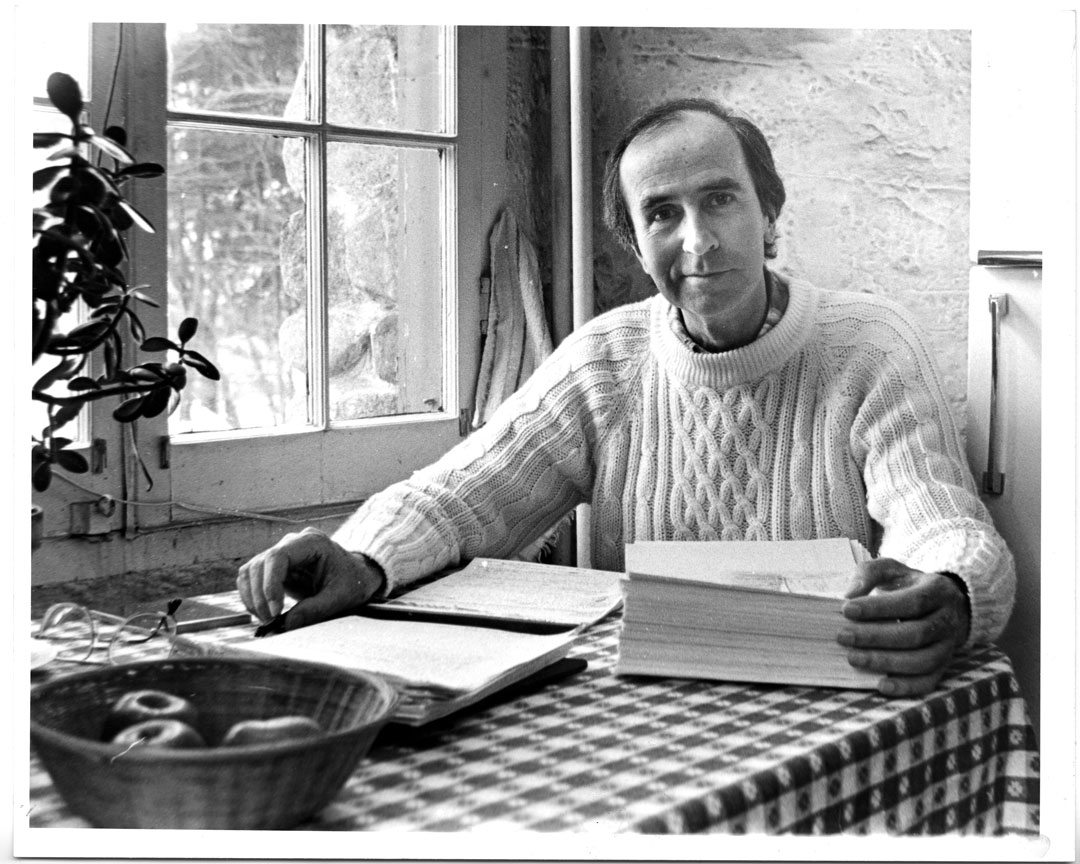

Members of Congress on Bicycles, Stewart McKinney Papers

The Clean Air controversy was exacerbated by environmental taxes on “indirect sources”—such as mall parking lots—in which large numbers of pollution-causing automobiles could potentially congregate. Again, while many environmentalists favored this notion, private industry owners and especially urban renewal project developers such as those in charge of the Stamford Downtown urban redevelopment project, felt that the Clean Air Act delivered a direct and unnecessary blow to their interests in this regard (CAA Folder, Box 23).

Similarly, the more that was learned about the detrimental effects of aerosol fluorocarbons at this time, the more agitation there was for regulation of these greenhouse gases, as well, given their potential to destroy the earth’s ozone layer. In addition to many other undesirable complications, it was revealed in 1974 that fluorocarbons caused “a chemical reaction that led to a breakdown of the ozone belt […] and dramatic changes in world weather patterns” (“Clean Air Act Amendments, 1976”).

The amendments to the Clean Air Act were not passed until 1977. These amendments included among others the extension of auto emission standards for two years, the extension of air quality standards for U.S. cities for five-to-ten years, and a three-year extension for air polluting industries to comply with standards before facing significant fines (“Clean Air Act Amendments, 1977”). However, debates over altering the act continued in the ’80s, and legislation was finally later passed in 1990. This legislation imposed greater federal standards on limiting smog, auto exhaust, toxic air pollution, etc. The 1990 amendments also included a measure that would foster more research on global warming, so that scientists and politicians alike could understand the pollution-induced worldwide environmental changes attributed to this phenomenon (“Clean Air, 1989 – 1990”).

Thus, although it wasn’t defined as such in the ’70s, global warming was the ultimate culprit behind the debate in Congress—the debate that unfortunately remains heated in recent times. In fact, the “Clear Skies” program presented by the Bush administration in 2002 was perhaps most controversial as it proposed to alter the CAA using a more market-driven approach supported by the power industry. However, this initiative was eventually rejected by environmentalists for its failure to regulate carbon dioxide emissions in addition to sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and mercury (“Clean Air, 2003-2004”). This debate actually resurfaced only a year ago, when the proposed 2010 Clean Air Act Amendments were rejected. Interestingly enough, although this bill did address issues regarding the ozone layer, it still failed to touch upon the regulation of carbon dioxide emissions. Needless to say, the proposed bill did not become a law.

Krisela Karaja, Student Intern

Resources:

Clean Air Act Folder, Box 23 (1975), Stewart B. McKinney Papers. Archives and Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

“Clean Air, 1989-1990 Legislative Chronology.” In Congress and the Nation, 1989-1992, vol. 8, 473. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 1993. <http://library.cqpress.com/catn/catn89-0000013636>.

“Clean Air, 2003-2004 Legislative Chronology.” In Congress and the Nation, 2001-2004, vol. 11, 437. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2006. <http://library.cqpress.com/catn/catn01-426-18057-965103>.

“Clean Air Act Amendments, 1976 Legislative Chronology.” In Congress and the Nation, 1973-1976, vol. 4, 303. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 1977. <http://library.cqpress.com/catn/catn73-0009171007>.

“Clean Air Amendments, 1977 Legislative Chronology.” In Congress and the Nation, 1977-1980, vol. 5, 535. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 1981. <http://library.cqpress.com/catn/catn77-0010172918>.

Environment—Air Folder, Box 16 (1974), Stewart B. McKinney Papers. Archives and Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Environment—Air Folder, Box 28 (1976), Stewart B. McKinney Papers. Archives and Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Stewart McKinney to D.W. Sweeney, May 24, 1974, Environment—Air Folder, Box 16, Stewart B. McKinney Papers. Archives and Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Stewart McKinney to Joel M. Berns, July 1, 1975, Clean Air Act Folder, Box 23, Stewart B. McKinney Papers. Archives and Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

United States. Cong. Senate. Clean Air Act Amendments of 2010. 111th Cong. S. 2995. GovTrack.us. Civic Impulse, LLC. Web. 11 Nov. 2011. <http://www.govtrack.us/congress/billtext.xpd?bill=s111-2995>.