Music from the film Beat Girl, 1960. From the Ann Charters Papers

Opening credits for the film:

UConn Library

Archives and Special Collections Blog

UConn Library

Archives and Special Collections Blog Carey MacDonald is an undergraduate Anthropology major and writing intern. In her blog series Through the Lens of an Anthropologist, Carey analyzes artifacts found in the collections of Archives and Special Collections.

Carey MacDonald is an undergraduate Anthropology major and writing intern. In her blog series Through the Lens of an Anthropologist, Carey analyzes artifacts found in the collections of Archives and Special Collections.

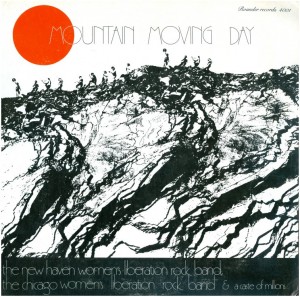

The Alternative Press Collection contains a series of LP (long-play) record albums by female musicians of the twentieth century whose music reflects the first and second waves of the women’s liberation movement. Two of these LPs are the post-first wave Mean Mothers Independent Women’s Blues LP and the second wave era New Haven and Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Bands’ Mountain Moving Day LP. Through the use of powerful, explicit lyrics and the moving techniques of blues and rock music, both LPs grapple with the issues of women’s rights, equality, and activism. They are timeless, auditory representations of the turbulent social contexts from which they came, and as such, they represent the century-long development of women’s rights awareness.

Volume 1 of the Mean Mothers Independent Women’s Blues album was produced in 1980 by Rosetta Reitz of Rosetta Records in New York, New York. According to Duke University Libraries’ Inventory of the Rosetta Reitz Papers, Reitz was a feminist writer, lecturer, and owner of Rosetta Records, which produced re-releases of female jazz and blues musicians’ songs from the early twentieth century. The LP’s gatefold cover, as mentioned by Graham Stinnett, the Curator for Human Rights Collections, contains biographical information about the female blues singers of the 1920s-1950s who are represented on this album.

Also, according to other content on the gatefold, the title’s term “mean mother” is meant as a compliment to all women, including those represented in the album, in that it is

a positive view of an independent woman, granting her the regard she deserves as one who will not passively accept unjust or unkind treatment.

The gatefold also states that these female singers were not just mourning lost love “in spite of the historic stereotyping imposed on them”, but were actually exploring every aspect of life through their music. These songs were created after the first historical wave of the women’s liberation movement ended in 1920, the year in which women were finally granted the right to vote. Yet despite the creation of this Constitutional amendment, the issue of women’s equality remained contentious. This is apparent when listening to the Mean Mothers album, which contains sixteen songs in total. For instance, Bessie Brown’s 1926 “Ain’t Much Good in the Best of Men Nowdays” laments that “married men have a tendency to roam,” while Bernice Edwards’ 1928 “Long Tall Mama” righteously claims that she is her own, independent woman and shall stand tall against adversity from men and other people in her life. On side B, Lil Armstrong’s 1936 “Or Leave Me Alone” ends with a long bluesy musical accompaniment, adding to the strength of the piece, much like Gladys Bentley’s deep, strong voice does in her 1928 song “How Much Can I Stand?” on side A.

Years later, during the second wave of the women’s liberation movement, The New Haven Women’s Liberation Rock Band and the Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band collaborated to create their 1972 nine-song album entitled Mountain Moving Day through Somerville, Massachusetts-based Rounder Records. The second wave was characterized by similar social issues pertaining to women’s rights but with particular regard to women’s equality in the workplace and a woman’s right to choose.

A woman’s right to choose is dealt with in the New Haven band’s “Abortion Song” in which Jennifer Abod and her accompanying vocalists demand for their right to choose singing, “Free our sisters; abortion is our right.” Their frequent use of “sister” works to establish a common sense of sisterhood between themselves and other women. This term is also heavily used in “So Fine” as in the lyric “Strength of my sisters coming out so fine.” While the New Haven band’s songs deal more with female sexuality, the Chicago band’s songs work to oppose stereotypical women’s gender roles in songs such as “Secretary” and “Ain’t Gonna Marry.”

Ultimately, these female bands produced music in a similar vein as their jazz and blues predecessors indicating their intent to develop and maintain a nationwide women’s rights consciousness that is rooted in the past century and yet relevant today.

Carey MacDonald, writing intern

Carey MacDonald is an undergraduate Anthropology major and writing intern. In her blog series Through the Lens of an Anthropologist, Carey analyzes artifacts found in the collections of Archives and Special Collections.

The Beat poets characterized themselves as non-conformists who dismissed the growing materialism of 1950s American society in order to lead a freer, more spontaneous lifestyle. The poetry of Jack Kerouac reflects the Beat ethos, and it is within the collection of spoken word records that we find several LP albums on which Kerouac recites his own poetry to the tune of music.

Poetry for the Beat Generation is the result of the 1959 collaboration of Jack Kerouac and composer Steve Allen under New York’s Hanover-Signature Record Corporation. According to the LP’s jacket, this recording session lasted only an hour, as decided by both Kerouac and Allen who felt that this first, improvised recording sufficed – and it certainly did. Their unusual collaboration illustrates through words and music the curious life of the nonconforming individual. In “October In The Railroad Earth” Kerouac warbles about the many different people he sees in the diverse city of San Francisco. This poem is like Kerouac’s own sociological study: he juxtaposes the rushing commuters with newspapers in hand with the roaming “lost bums” and “Negroes” of the “Railroad Earth.” Kerouac furthers this theme of dualism when he remarks about things as ordinary as the movement of day to night and from sunny, blue sky to deep blue sky with stars.

Despite this thematic duality however, it is apparent that Kerouac does not mean to draw distinctions between the groups of people he observes. Instead he familiarizes himself with all sorts of people, breaks down the social divisions separating them, and lives among them: “Nobody knew – or far from cared – who I was all my life, 3,500 miles from birth, all opened up and at last belonged to me in great America.”

While “October In The Railroad Earth” is comprised of his momentary observations of the world, Kerouac’s recitation makes these observations inherently complex and compelling. The unique combination of his deep Lowell, MA accent with his precise word placement, expressive diction, and comical use of onomatopoeia makes this particularly vivid poem grab the attention of and resonate with the listener. Kerouac also tends to end his phrases with an upward inflection instead of dropping the last word to give pause to his thoughts. This is indicative of the almost never-ending stream of consciousness that runs through his mind, just like what each of us experiences every day.

Steve Allen’s improvised jazz piano accompaniment further enhances the potency of Kerouac’s recitations in that it reinforces the tone of the poem. In the case of “October In The Railroad Earth,” Allen’s rifts become fast and exciting when Kerouac discusses the busy commuters and then mellow out when day becomes night and when Kerouac comments on California’s “end of land sadness.”

“The Sounds of The Universe Coming In My Window” also reflects on an individual’s everyday sensory experiences, such as listening to the humming of aphids and hummingbirds or marveling at the trees outside. Allen’s piano and Kerouac’s alliteration and echo amplify the “sounds of the universe” described in this poem.

The somber piano accompaniment on “I Had A Slouch Hat Too One Time” establishes the wistful tone of Kerouac’s poem in which he laments that perhaps he does not belong with the Ivy League men of New York City who wear slouch hats and Brooks Brothers slacks and ties. Instead, on top of a now whimsical piano melody, he tells a (most likely) fictional tale about consuming drugs in the bathroom of a store in Buffalo, NY and then proceeding to steal a man’s wallet and begin a shoplifting spree. This poem clearly reflects the non-conforming values of the Beats and calls into question the value of the posh lifestyle of the men described in the poem.

Jack Kerouac and Steve Allen’s Poetry for the Beat Generation effortlessly reveals the dissenting ideals of the Beats, and across the span of American history we see a similar pattern of social disdain for the status quo.

Carey MacDonald, writing intern

Dr. Lisa Sanchez Gonzalez, associate professor in UConn’s English Department, has published a new book on Pura Belpre, the storyteller, author and librarian at New York Public Library who brought Puerto Rican folklore and the needs of bilingual children to light. In addition to extensive biographical information about Belpre and a selection of pictures, Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez has included 32 of Belpre’s stories and 12 essays. The essays range from such topics as “The Art of writing for children” to “Library work with bilingual children.”

Cover, The Stories I read to the children: the Life and writing of Pura Belpre, the legendary storyteller, children’s author, and New York Public Librarian by Lisa Sanchez Gonzalez (New York : Hunter College, 2013).

One of Belpre’s delightful stories that Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez has selected for inclusion is “The Parrot who liked to eat Spanish Sausages.”

Once there was a parrot who liked to each Spanish sausages. Every day he would saunter into the kitchen, watch for the cook to leave for a few minutes, then snatch the Spanish sausages from the pot and saunter out before she came back.

At last the cook became suspicious and decided to watch the parrot. One day she hid behind the kitchen door and waited for the parrot to come. She had placed on the table a pot of vegetables with a string of sausages, as she often did before she lit the fire.

By and by the parrot came sauntering in. He went straight to the table, lifted the pot’s lid, took out the string of sausages, and made short work of them. Then off he sauntered again.

The cook said not a word. But later on, when she had placed the pot on a low fire, and the water was lukewarm, she picked up the parrot and poked his head into the pot. The parrot lost all of his head feathers and never again snuck into the kitchen to lift the Spanish sausages out of the pot.

One day a very important guest arrived to visit the family. And, as he often did, he overstayed his visit. Since it was time for dinner the family invited him to eat with them. The guest accepted graciously. While they ate, the parrot sauntered into the dining room. He circled the table twice, then flew up and sat on the guest’s shoulder. Suddenly he noticed that the guest’s head was completely bald. “So,” the parrot cried, “you too like to eat Spanish sausages!” And laughing and screeching the parrot flew out of the room.

Wednesday, April 17th is Take Back the Night on the University of Connecticut campus. An event recognized across North America in response to violence against wimmin. Since its inception Take Back the Night has been about reclaiming space beyond the physically passive act of recognition and observation. Wimmin, the disproportionate victims of domestic violence, rape, sexual assault and harassment, have found solidarity through the action of speaking out and mobilization en masse against this violence. It’s sister mobilization, Slutwalk, has also achieved support across the broad spectrum of wimmin who experience patriarchy in the streets, an intended social space for interaction in work, transit and play.

The Alternative Press Collection (APC) in the Archives contains numerous publications on wimmin-positive theory and praxis in response to gender violence since the 1960s. Of note is the feminist publication Aegis: Magazine on Ending Violence Against Women published in 1978 by the Feminist Alliance Against Rape. Defined by the magazine’s statement of purpose, the movement to build solidarity through information was seminal in establishing wimmin’s resources in regions where silence was (is) the normative response to gender violence:

The purpose of Aegis is to aid the efforts of feminists working to end violence against women. To this end, Aegis provides practical information and resources for grassroots organizers, along with promoting a continuing discussion among feminists of the root causes of rape, battering, sexual harassment and other forms of violence against women.

Depicted in the image below is the cover of the September/October 1979 issue, portraying the advocacy debate around wimmin’s rights to self defense.

In addition to our extensive APC collection of periodicals is a recently acquired special collection art installation about building solidarity and non-violence amongst wimmin through art therapy. In this case, pulping panties into paper! From the Peace Paper Project comes another alliterative piece, Panty Pulping! The installment consists of loose pieces of paper made from mulched wimmin’s underwear that has been forged anew through storytelling and constructing the foundations of a new page for which a narrative can be written about wimmins voices together.

To view these pieces or any materials about wimmin’s rights and radical feminism, please contact the curator.

Darlin’ Corey in the Fireside Book of Favorite American Songs. From the Billie M. Levy Collection. Never heard Darlin’ Corey? Try this.

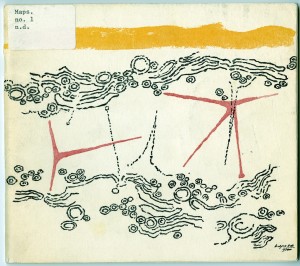

Celebrate National Poetry Month by exploring today’s poets and poetry available from our friends at the living-breathing heart of the now: poetry portals. These sites bring to the 21st century a tradition of independently curating, collecting and publishing poetry that existed during the mimeograph revolution of the 20th century. Kin to the muscular-yet-short-lived little magazines that thrived in the 1960s and 1970s, they are realms of the extraordinary, offering what the poet John Taggart in Number 1 (1969) of his little magazine Maps, describes as

…Poems [that] are not on the furthermost borders of the avant-garde. They are of the now in the continuum sense of ‘being’ – eyes open, perhaps screaming, but not leaping out of the present, and occasionally, they are of the past as renovated by those open eyes.

Students’ actions at the University of Connecticut during the Vietnam War era were charged with radical and idealistic electricity. At a time when the student population was smaller, quieter, and only a third of the size that it is today, the on-campus presence of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) helped mobilize individuals who either did or did not associate themselves with the group. One action that took place on campus during this era was the ten-day long demonstration of December 1968. Producers A.H. Perlmutter and Morton Silverstein of National Educational Television captured this demonstration on film and turned it into the 1969 black and white production Diary of a Student Revolution.

The film suggests that the reason for that December’s unrest was that many students were strongly opposed to the principles of the companies conducting job recruitment interviews on campus. One such company was the DOW Chemical Company, the maker of both Saran Wrap and Napalm, a chemical weapon whose rampant usage in the Vietnam War became highly controversial in the U.S. in the late sixties. Students demonstrated against the university’s permission of DOW recruitment by first occupying the office of President Homer D. Babbidge in November 1968. SDS continued to garner support from some students and faculty and called for the student government to join their side on December 8, 2012. This was just the beginning of that December’s ten-day period of unrest.

Although the immediate cause of the December action was students’ opposition to recruiters on campus, interviews with students reveal the underlying moods and motivations advancing the demonstration. One individual stated, “Power, you know, is at the top; it’s held by a corporate elite. And the country is organized to protect the corporate elite.” Another student claimed that “this system cannot be tolerated and must be destroyed.” This severe distrust of American government and industry existed at a time when the Vietnam War was becoming more and more brutal and thus unpopular, and when social and civil rights activists like Abbie Hoffman and Martin Luther King, Jr. were at the forefront of the media.

In response to students’ and SDS’s call for a moratorium on recruiting starting on Tuesday, December 10, 1968, President Babbidge stated in a campus-wide announcement that, after great deliberation, there would be no moratorium on recruiting. Needless to say, that Tuesday saw the height of the action; people demonstrated against Babbidge’s announcement outside an off-campus building where recruiting was taking place. 67 students and faculty who weren’t formally associated with SDS were arrested by state police. The film shows that many of those individuals wished to be arrested to symbolize their dedication to the cause.

Contrarily, in an impromptu interview conducted in a lecture hall, a non-acting student called the acting students a “minority”, and one student claimed that the activists should be arrested and suspended. When a small number of SDS members entered that lecture hall to arouse their fellow students while the cameras were filming, a group of non-acting students shouted at them, “Keep the status quo, keep the status quo!” This debate would continue on until 1971, even after this specific period of action began to collapse on its ninth day.

The film also reveals President Babbidge’s tribulations during the demonstrations. Viewed by radical students as part of America’s ‘corporate elite’, Babbidge actually appears more conflicted and concerned than anything. We ultimately know from documents found in the President’s Office Records that Babbidge, too, believed in the same causes as the students, including racial, educational, occupational, and economic equality and justice. But he believed in pursuing different means to those ends. This can be seen in a statement he made on May 10, 1970 in response to another student action: “I can honestly say that I believe I understand the foundation causes of the student strike, I support many of them…but I cannot support the strike.”

The events of 1968 at the University of Connecticut indicate that the community struggled locally with issues that originated from society at large. Our university community continues to do the same today.

Carey MacDonald, writing intern