To drink or not to drink? This is a question most Americans rarely address, regarding the safety of their drinking water. Indeed, water contamination often appears irrelevant to us—a far-off issue confined to developing countries. However, as Jonathan King argues in his book Troubled Water: The Poisoning of America’s Drinking Water, instances of environmental contamination are far from isolated.

Written in 1985 by the Center for Investigative Reporting, one of the nation’s oldest nonprofit agencies covering crucial yet often neglected issues, Troubled Water raises awareness about contaminated groundwater. Burying toxic wastes is particularly harmful to groundwater –and, by association, drinking water—because chemicals “don’t readily disperse, settle out, or degrade” (King xi) at this level. Land disposal is a cheap, common, and sometimes significantly harmful waste management technique, as there is no way to fully ensure that the toxins will be kept from leaking into groundwater. In fact, “a leak of a single gallon of gasoline per day is enough to render the groundwater supply for a town of 50,000 people unfit to drink” (King xi).

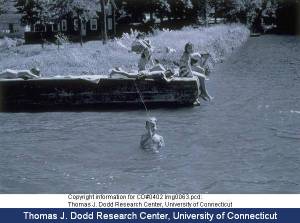

Such contamination has had dire results in the past: the 1978 Love Canal scandal being one example. Despite warnings from Hooker Chemicals Co., schools and residential areas were built on and near a buried chemical waste site in Niagara Falls, NY. Wastes and toxins such as dioxin eventually spread as the water table rose—leaking into basements, sewers, and eventually area creeks. This contamination was also associated with an unprecedented number of health concerns among residents including miscarriages, birth defects, and the development of rare diseases.

Federal initiatives such as the 1980 Superfund program were established in the wake of these environmental scandals in order to hold polluters accountable after the fact. However, King suggests that the best way to seek environmental justice is for citizens to be proactive, so that environmental injustice never becomes an issue. He argues that “contamination has to be prevented before it happens” (173). He quotes Lois Gibbs, a prominent environmentalist and local leader in the call for action at Love Canal: “ ‘I’m really very optimistic. I see people moving, and I see things [i.e. citizen involvement] happening’ ” (180). If not, then, as Joel Hirschhorm—a 1980s Capitol Hill expert on toxic waste management—put it: “We will end up paying that [environmental] debt either with our money [in having to treat polluted areas] or our health” (qtd. in King xiv-xv).

Krisela Karaja, Student Intern

Resources:

“About CIR.” Center for Investigative Reporting. Center for Investigative Reporting, n.d. Web. 26 Sept. 2011. Center for Investigative Reporting

DePalma, Anthony. “Love Canal Declared Clean, Ending Toxic Horror.” New York Times 18 Mar. 2004. Web Archives. 26 Sept. 2011. http://www.nytimes.com/2004/03/18/nyregion/love-canal-declared-clean-ending-toxic-horror.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm.

King, Jonathan. Troubled Water: The Poisoning of America’s Drinking Water—how government and industry allowed it to happen, and what you can do to ensure a safe supply in the home. Emmaus Pennsylvania, Rodale Press: 1985. Print. Alternative Press Collections. Archives and Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries. Call number: APC Bk 389.

“Love Canal New York. EPA ID# NYD000606947.” EPA. United States Environmental Protection Agency, 25 Jan. 2010. Web. 26 Sept. 2011. <www.epa.gov/region2/superfund/npl/0201290c.pdf>.