[slideshow_deploy id=’9160′]

For more than a century, the E. Ingraham Company was a prominent family-operated manufacturer of clocks and watches, with headquarters and plants located in Bristol, Connecticut. Most of its employees were natives of the Bristol region, and members of the Ingraham family of Bristol controlled its management.

The company was founded in 1831 by Elias Ingraham (1805-1885), who opened his own shop in Bristol as a cabinetmaker and designer of clock cases. After several mergers with other companies and name changes the company was known as E. Ingraham and Company by 1884. From 1884 to 1958, the period during which most of the surviving company records were created, the firm was known as E. Ingraham Company. In 1958, the name was changed to Ingraham Company, and in November 1967, when the company was sold to McGraw Edison Company, it became Ingraham Industries.Through much of the company’s history, members of the Ingraham family served as its presidents and in other official capacities. The last to hold the office of president was Dudley Ingraham, until 1954.

E. Ingraham Company’s products throughout its history reflected technological advances and changing consumer demands for timepieces. Until about 1890, the company manufactured only pendulum clocks. During the 1890s, they began making lever escapement time clocks and alarm clocks. Radical changes in manufacturing methods during the following decade enabled E. Ingraham Company to produce 30-hour alarm clocks, pocket watches (1914), and 8-day alarm lever and timepieces (1915). In 1913 the company began to manufacture the popular “dollar watch.” In 1930, Ingraham added non-jeweled wrist watches and in 1931 began marketing electric clocks.

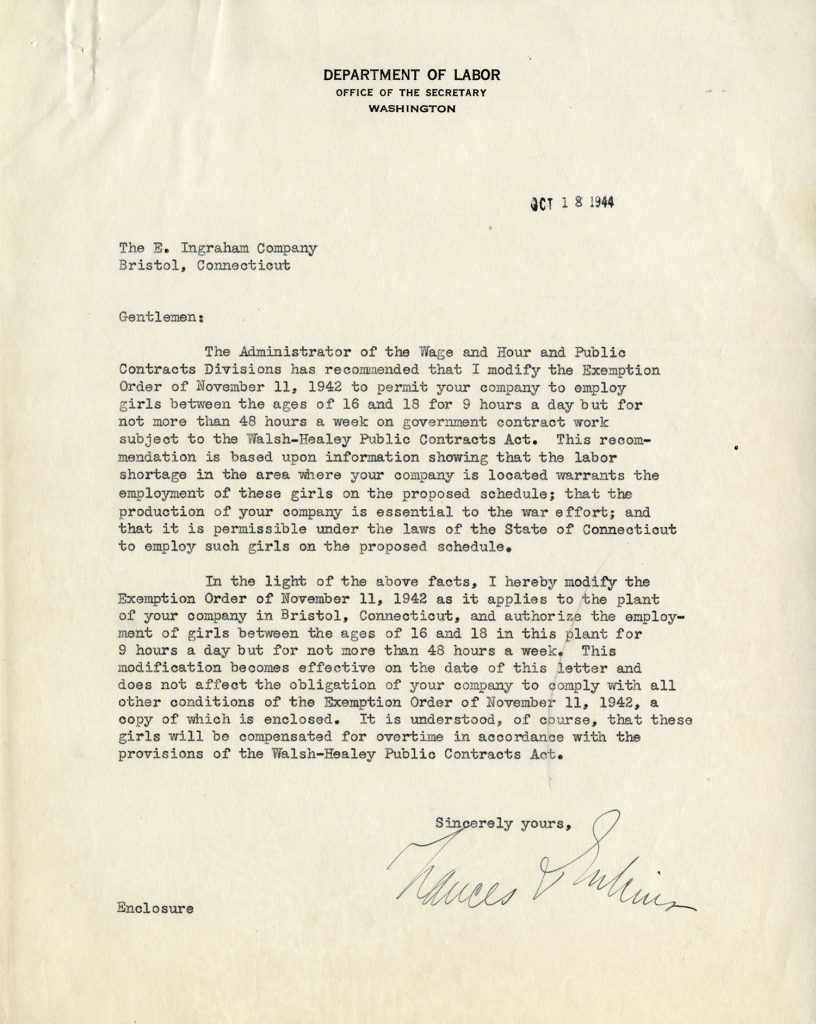

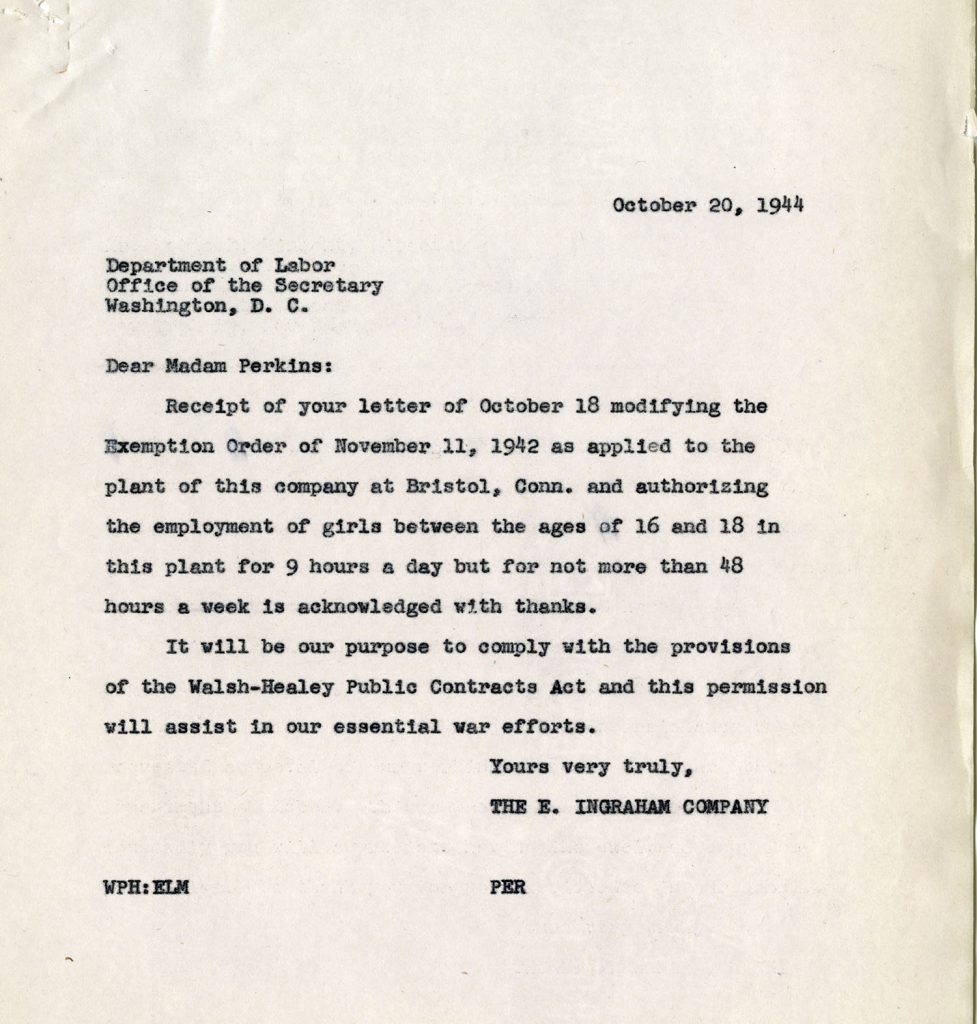

The depression of the 1930s did not affect E. Ingraham Company as severely as it did many other businesses. Employment never dropped more than 15% and wage and salaries were not cut. By the beginning of the Second World War, the company was producing clocks and watches at maximum capacity in order to meet the great export need after many European supplies were cut off. However, in 1942 the War Production Board ordered E. Ingraham Company to cease manufacture of all clocks and watches. By August 1942 the company had entirely re-tooled for production of items of critical war use, such as mechanical time-fuse parts for Army and Navy anti-aircraft and artillery. Full production of clocks and watches was not resumed until 1946, but the years 1946 to 1948 were boom years for company sales.

The company was sold to McGraw Edison Company in November 1967 and its name changed to Ingraham Industries.

In 1980 the company donated its records to the University of Connecticut Library. They consist of account books, general business records, correspondence, printed materials, photographs, maps and drawings which document the company’s history from 1840-1967. Also included are general accounting and administrative records; records relating to sales, purchasing, production, and labor; subsidiary company records. The general correspondence, which comprises more than half of the records, is particularly voluminous for the years 1916-1947.

Now available online in the UConn Archives digital repository is a set of sales catalogs of the E. Ingraham Company’s clocks and watches, beginning at http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:19800034Catalogs. These catalogs are a terrific resource for clock collectors and historians.