The following guest post is by Elizabeth Barnett, recipient of the 2019 Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant. Ms. Barnett is an assistant professor of English at Rockhurst University in Kansas City, where she is the director of the Midwest Poets Series and editor of the Rockhurst Review. Her essays and poems have appeared in Modernism/modernity, Gulf Coast, and The Massachusetts Review. She is working, with great pleasure, on Marshall’s literary biography, tentatively titled Egads!

“But how then can you really care if anybody gets it, or gets what it means, or if it improves them. Improves them for what? For death? Why hurry them along? Too many poets act like a middle-aged mother trying to get her kids to eat too much cooked meat, and potatoes with drippings (tears). I don’t give a damn whether they eat or not.”

—Frank O’Hara, “Personism”

James Marshall’s voice had two kinds of

drawls, the homey “ahs” of his Texas childhood—“I was told y’all are shy. You

can’t be any shyer than I am”—and the playful “ohs” of the queer, East Coast

communities he moved to soon after—“I live in New York as well as Connecticut

and I go to galleries all the time and everything I see in painting is soooooo

dull, suuuuuuch crap.” Marshall’s voice maps his identity. It also conceals it.

A voice, as opposed to the words it speaks, can’t be “on the record,” so can

supplement, complicate, and contradict those words.

I knew Marshall’s authorial voice—witty,

warm, and weird—from gentle hippo friends George and Martha; sweet teacher Miss

Nelson and her witchy alter ego, Viola Swamp; and the tragiocomedic Stupid

family.[1]

More than 25 years after his death, I

came to know Marshall’s actual voice when University of Connecticut archivist

Kristin Eshelman guided me to an amazing and extensive cache of recordings.

From 1976 to 1990 Marshall visited his friend, one-time landlady, and devoted

admirer, Francelia Butler’s “kiddie lit” class most semesters, reading his

stories; chatting about the art world, publishing industry, and their

intersection in picture books; and, most revealingly, participating in

Q&As. Thanks to the generosity of Billie Levy and the University of

Connecticut Libraries, I was able to listen to the run of these tapes, which

begin at the peak of Marshall’s career and end two years before his death of

complications from AIDS.

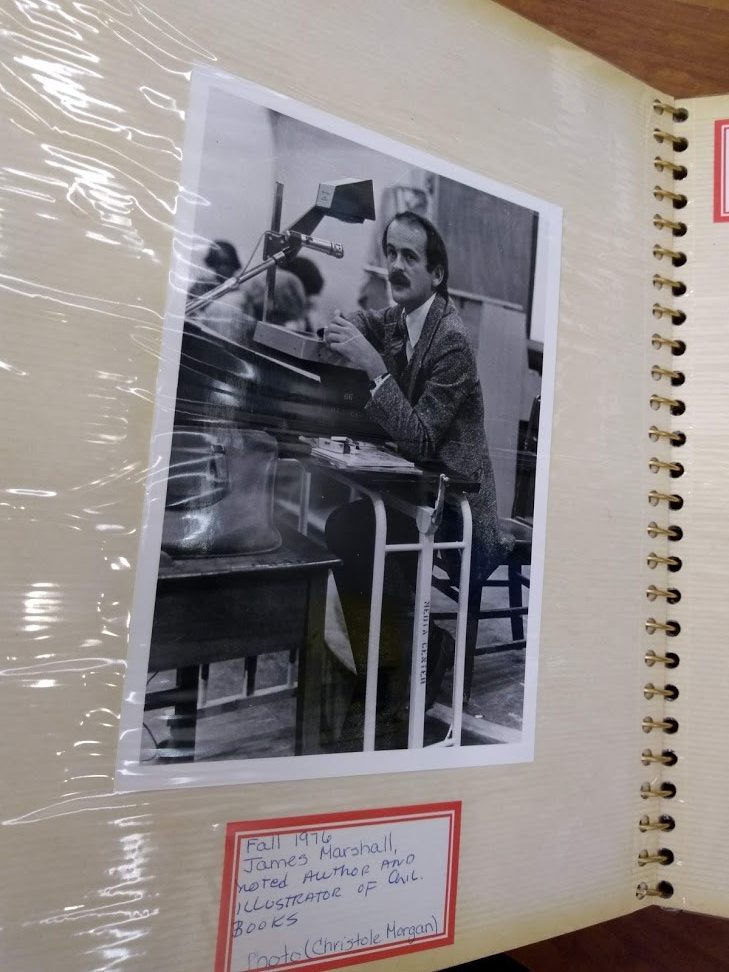

Marshall’s first visit, from the Fall 1976 class photo album. (The class made a photo album!). Francelia Butler Papers, Archives & Special Collections, University of Connecticut Library

A question I had for the tapes: how did

Marshall navigate being a gay artist at a time when it was, full stop,

impossible to be an openly gay man making books for children? Eavesdropping on

those Regan-era, AIDS-blighted years, I never heard Marshall say he was

gay. He never spoke as though he

weren’t. Marshall’s authorial persona, distilled in his voice, suggests a key

insight about his books, which also had to straddle the line between authentic

artistic creations and market-dictated norms. What he says and how he says it

are analogous to the words and pictures in one of his books. The voice says

what the words can’t, just as the pictures, at times, undercut the moralistic

conventions of children’s literature.

In Butler’s classroom, for example, I

heard Marshall gesture to the limits of what he was allowed to say in an

October 10, 1979, interaction with a female student. The student asked if

Marshall was married. Marshall answered first with several beats of silence,

then with a single word, “no,” then another beat of silence, then “I’m not”

followed by a dismissive “next question.” The question asker perhaps wanted to

catch Marshall out or perhaps didn’t understand what Marshall’s voice had been

telling her. She asks an “innocent,” superficially unobjectionable question.

But that banal surface hides (or not) the power of the dominant culture that

the question summons. It really asks: Are you one of us? The asker uses the

language of power and Marshall subverts that language by making it superfluous,

his answer conveyed through silence and tone, not the words themselves.

This brief interaction reminded me of

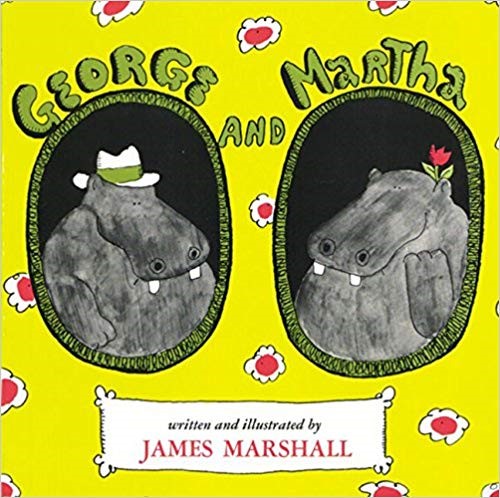

“Split Pea Soup,” the first story in 1972’s George

and Martha, Marshall’s first book as both author and illustrator. It

begins, “Martha was very fond of making split pea soup. Sometimes she made it

all day long. Pots and pots of split pea soup.” These three simple sentences

amplify each other and give a sense of something a little off about Martha’s

soup making, the repetition mirroring Martha’s repetitive actions, recasting

conventional domesticity as a less-cozy compulsion. Why is she making soup all

day long? Why is she making so much? What begins in a normal place ends in a

slightly absurd one. Or perhaps it’s just that the absurdity of normality comes

through in the repetition. In the illustration, the framed slogan “Soup’s On”

underlines Martha’s extreme enthusiasm for soup.

James Marshall, George and Martha

The illustration shows Martha, a hippo,

in a massive checkered apron tied with an equally massive bow. She wears no

other clothes. Her performance of femininity draws attention not to her

femininity but its status as performance. (Here I echo and Marshall anticipates

Judith Butler’s theorization of performativity). She is a topless large animal

playing the part of a demure housewife. A drawn border surrounds the image,

emphasizing that, like Martha in the kitchen, the book itself is performing.

The redundant border puts “children’s story” in quotation marks by not allowing

the page itself to function as the boundary, by insisting on something more

artful, and by drawing attention to that artificiality.

So Martha loves making soup. We then

learn that George hates split pea soup but eats it anyway to make Martha happy.

However, he’s only hippo and reaches a point where he can eat no more. How,

though, can he tell Martha that this good, normal thing she’s doing makes him

miserable? He can’t—he pours the soup into his loafers. His pink loafers. And

Martha catches him.

James Marshall, George and Martha

“Light in his loafers” was a common

euphemism for homosexuality in the mid-century heyday of loafers and sexual

repression. Pink is coded as female or gay. Until a new, more economical method

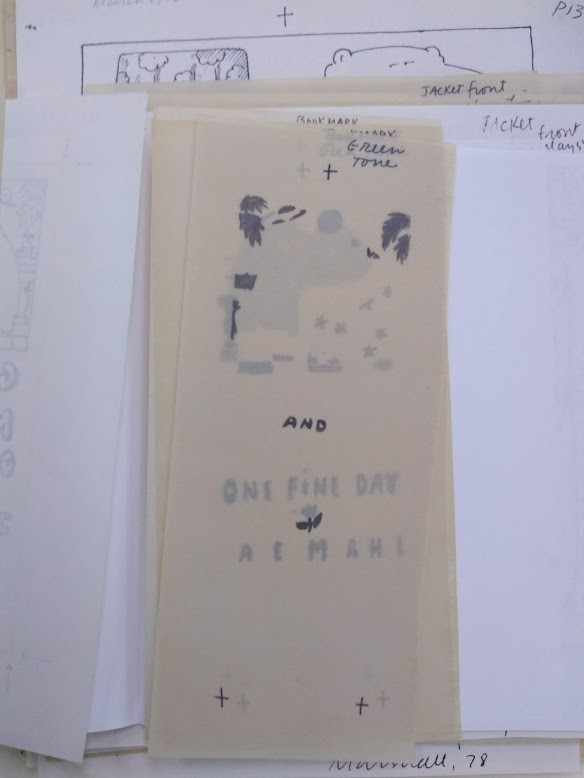

of full-color printing was pioneered in Japan in the mid-1980s, most of Marshall’s illustrations were color

overlays, which means that Marshall drew the picture then traced each thing

that he wanted to be yellow, or blue, or red onto separate sheets of paper and

colored those in with graphite, indicating if any colors were to be diluted by

giving the percentage of that color to be applied. All to say, the pink was

absolutely a deliberate choice.

Example of color overlay from George and Martha One Fine Day. de Grummond Children’s Literature Collection, University of Southern Mississippi.

George’s disposal of the soup in his

loafers might be read as a symbolic refusal of compulsory heterosexuality. It

is also a refusal of language, suggesting the complicity between the two.

George “says” he hates the soup through his actions because language would

imbricate him in the very power structure he’s resisting. I see Martha as the

question-asker here. She is playing the feminine role as she’s supposed to.

She’s aligned with the dominant culture. George is Marshall; he can’t tell

Martha he hates the soup because here she is doing exactly what she’s supposed

to do (however inane), and he’s messing it up. George avoids the language trap

just as author/illustrator Marshall does—they don’t put the subversive part

into words.

The too-pat ending of “Split Pea Soup,”—Martha

tells George, “Friends should always tell each other the truth,” and they eat

chocolate chip cookies—to me signals that Marshall wants his reader to feel the tension between what the story says

and what it means. I probably think that because that’s what I hear happening

in the classroom interactions on the archive’s audio tapes. Marshall’s

language, punctuated with strategic silences and curtness, insists on its own

inadequacy, drawing an arrow to what’s left out. The story’s sharp turn to the

didactic reads to me like the drawn border around the illustrations. It signals

its own performativity, here of the norms of the picture book, which are

weakened, rather than reinforced, by their inclusion.

Frank O’Hara’s 1959 critique of poetry-as-moral-vitamin

anticipates Marshall’s later refusal of children’s literature’s didactic

imperative. In both cases, queer writers already existed outside of mainstream

culture, their morality maligned by that culture. It follows they may have been

especially wary of the inherent value of literature being used for ethical

indoctrination. Both suggest the value of their art form is not the moments it

teaches us something, but the moments it refuses to.

In 1979 Marshall “answered” the student

question with words that would not endanger his art and livelihood. Marshall’s delivery suggests he wants the

audience to know that’s why he’s saying them. The performative conformity is

one way to understand the more conventional moments in Marshall’s startlingly

original body of work. He tells us when he’s playing by the rules to protect

the magic of when he’s not.

[1] The latter credit Harry Allard with authorship but, as Jerrold

Connors convincingly argues in his post on this site, and Marshall’s

materials confirm, Allard often provided the creative spark for a piece, but

Marshall shaped the narrative and the finished prose.

Introduce your class to primary sources from Archives and Special Collections, UConn’s only public archive that offers students opportunities to explore and experience original letters, diaries, photographs, maps, drawings, artists books, graphic novels, student newspapers, travel narratives, oral histories, and rare sound recordings to illuminate a given topic of study. With over 40,000 linear feet of materials – located in the center of campus at the Dodd Research Center – the Archives welcomes all visitors to its Reading Room, a quiet space to contemplate potentially transformative resources.

Introduce your class to primary sources from Archives and Special Collections, UConn’s only public archive that offers students opportunities to explore and experience original letters, diaries, photographs, maps, drawings, artists books, graphic novels, student newspapers, travel narratives, oral histories, and rare sound recordings to illuminate a given topic of study. With over 40,000 linear feet of materials – located in the center of campus at the Dodd Research Center – the Archives welcomes all visitors to its Reading Room, a quiet space to contemplate potentially transformative resources.