Anna Zarra Aldrich is majoring in English, political science and journalism at the University of Connecticut. As a student writing intern, Anna is studying historical feminist publications from the collections of Archives and Special Collections. The following guest post is the final post in the series.

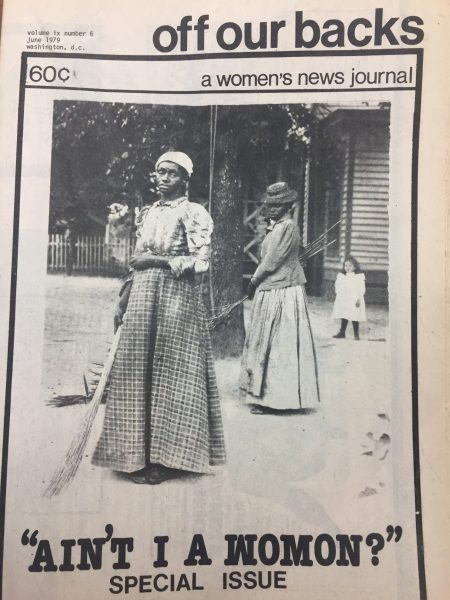

The feminist movement has long struggled with incorporating different groups’ concerns and modes of oppression into the movement. This problem was exacerbated by the multifaceted, turbulent U.S. political atmosphere that characterized the 1960s and 1970s. The differences between black and white women’s views of the movement clashed on several essential dimensions. But the issues of other minority groups were given less attention by the feminist movement, and by society in general, due to the fact that their ethnic/racial factions were much smaller than African Americans’.

Another marginalized group that galvanized in the activist culture of the 1960s and 1970s in America were Native Americans. These men and women sought to have their tribal autonomy recognized. They were also fighting issues such as environmentally harmful mining practices on their resource-rich lands and high rates of substance abuse and poverty within their communities.

Native American women had a unique relationship with the feminist movement because the issues this minority group faced were different from those that white or black women faced, and the ethnic population of which they were a part was a severely marginalized minority. U.S. Census data from 1970 shows that a whopping 98.6 percent of the total population was either white or black/African American (87.5 percent and 11.1 percent respectively). Native Americans constituted less than .004 percent.

Native Americans were fighting for their unique political rights as well as larger environmental concerns during this period.

The March 1977 issue of “Off Our Backs” includes an article summarizing the findings of a report by the Association on American Indian Affairs (AAIA), a non-profit organization founded in 1922 to promote the well-being of Native Americans and Alaskan Natives. The report found that Native American children are placed outside of their families at a rate 10 to 20 times higher than that for non-Native American children.

The AAIA argued that this practice deprives Native American children of the ability to be raised with a proper awareness of and appreciation for their culture. This concern emphasizes the fact that Native American women who were involved in the feminist movement during this time were simultaneously combatting the United States government’s systematic efforts to diminish their independence and culture as well as the wide-spread sexism that was the feminist movement’s main concern.

Native American culture celebrates its strong connection to and appreciation of nature. When Native American tribes were forced off their lands in the nineteenth century, they were put on reservations in states like Oklahoma and South Dakota. The U.S. government later came to realize these areas were rich with natural resources such as oil and uranium.

“In the days of diminishing U.S. energy resources, the push is on to take what’s left of Indian land,” according to an article in “Off Our Backs.”

The U.S. government used environmentally hazardous practices to extract these resources, exposing people living on the land to cancer-causing radioactive materials. It also paid the Native Americans working in these hazardous mines very low wages. These practices led to outcry by Native American men and women.

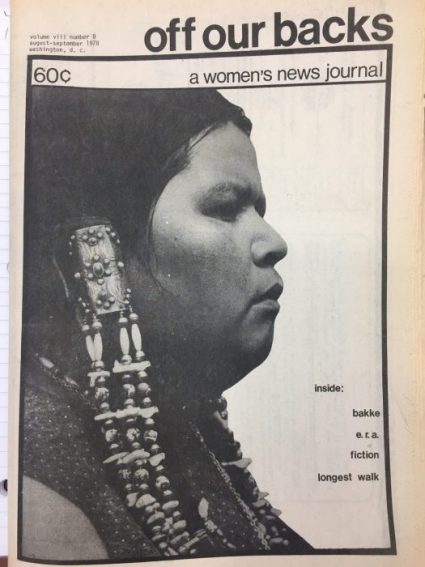

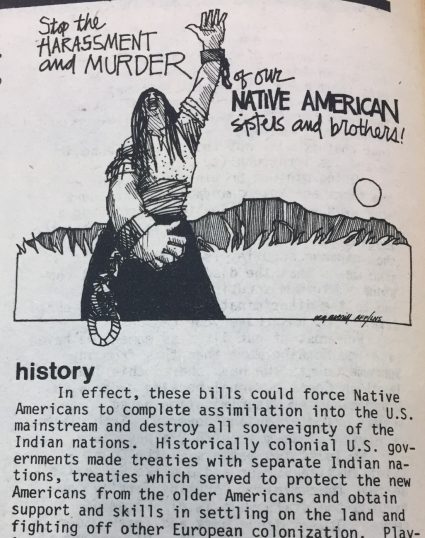

In 1978, thousands of Native Americans participated in The Longest Walk, a protest organized to bring attention to threats to tribal lands pose by several pieces of proposed legislation.

“In effect, these bills could force Native Americans to complete assimilation into the U.S. mainstream and destroy all sovereignty of the Indian nations,” the article on the march said.

In the same August/September 1978 issue that covered the march, “Off Our Backs” included coverage of a conference in New Mexico that addressed the upsurge in domestic violence against Navajo women. This increase was attributed to a “pressure cooker syndrome” created by white culture: “women-battering and child abuse (were) once practically non-existent…and has now reached crises proportions.”

The attempted forced assimilation of native people into white culture created a class system that did not exist in Navajo tribal society. This led to high poverty and unemployment rates which in turn came to be correlated with high rates of substance abuse and domestic violence.

The writers draw attention to the fact that few of the speakers at the conference were from the Navajo or from any other Native American community. Calling attention to the lack of authentic representation at this conference may be an indication of the evolution of “Off Our Backs” in how it dealt with minority issues. When the paper first began in 1970, it struggled to expand their coverage to minority women’s issues, as evidenced by its problematic coverage of a black feminist group’s conference in 1974.

Similar to black women who were involved with groups like the Black Panthers, politically active Native American women were part of efforts led by men. Women of All Red Nations (WARN) was a Native American women’s group that brought attention to issues that affected their community including the displacement of their children, forced sterilization, tribal rights, resource exploitation and racism in the educational system. The group invited several Native American men to speak at a conference it held in South Dakota in 1978 as it did not “believe in the separation of men and women who were working for the same objective.” This serves as a perfect parallel to black women activists who wanted to be a part of the black and feminist movements.

Burning Cloud’s letter serves as a quintessential example of a woman’s struggle to find a way to be politically active as someone with a complex set of oppressed identities.

In the December 1978 issue of “Off Our Backs,” the editors printed a letter from Burning Cloud, a self-described “Filipina/Indian Dyke.” In the letter, Burning Cloud shared a sentiment common with those expressed by black women — that she was “Indian first and above all other matters.”

Burning Cloud felt she could not be both an Indian and a gay woman in society. She also expressed frustration with the fact that non-black minorities’ concerns are much more widely disregarded because there are comparatively few of them in number.

Burning Cloud’s letter included a call to action for environmental activism which, from her perspective, was something of which native people were much more conscious due to their spiritual cultural connections to the earth.

“If Mother Earth is to die WE ALL DIE. Think about that one. What is the future of your children and sisters and mothers to be?” she wrote. “Are we not killing each other because we allow such things as racism, classism, separatism right here in the Lesbian community. How shall wimmin be totally free when three-quarters of the (Coloured Wimmin) are dying?”

(Feminists took to using alternative spellings of “women” and “woman” in order to avoid using the masculine root of those words.)

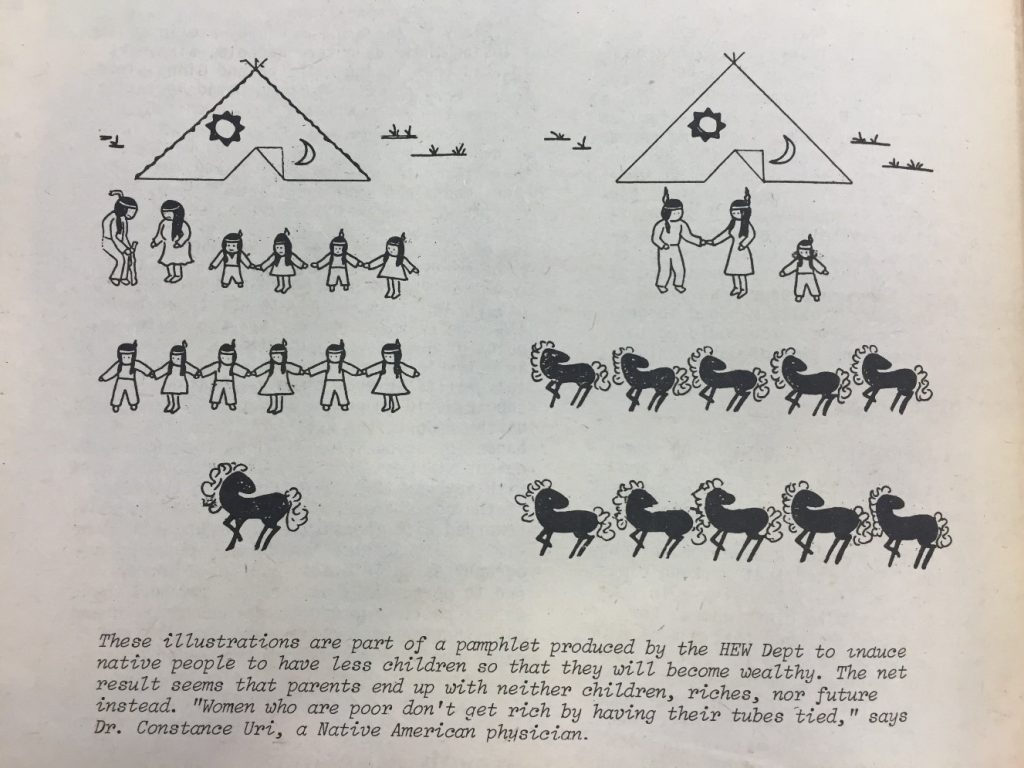

Native American women also faced the issue of forced or coerced sterilization. In “Off Our Backs” article from December 1978, WARN said that 25 percent of Native American Women were forcibly sterilized.

During this period, the United States government instituted polices of population control that targeted minority, underclass women. One third of Puerto Rican woman of reproductive age had been sterilized in 1976. This policy was veiled as a necessary method of population control that would help Puerto Rico develop economically. However, many argued that the problem was not overpopulation, rather that the available resources were concentrated in the upper echelons of society.

In her 1976 University of Connecticut Ph.D. thesis “Population Policy, Social Structure and the Health System in Puerto Rico: The Case of Female Sterilization,” Peta Henderson found that in addition to medical reasons, the law in Puerto Rico regarding female sterilization allowed for women to be sterilized or use other contraceptive methods in cases of poverty or already having multiple children. Henderson found that most sterile Puerto Rican women said they voluntarily chose to have the operation. However, she explores how this choice was corrupted by the fact that government actors worked to persuade these women that sterilization was in their best interest.

The U.S. Government put forth the idea that having fewer children was the surest path to wealth for minority women, ignoring institutional issues including racism and sexism that impeded their social mobility.

These kind of population control polices were also implemented elsewhere in Latin America.

The April 1970 issue of “Off Our Backs,” a female member of the Peace Corps who went to Ecuador said, “Providing safe contraceptives must be a part of a comprehensive health program,” Rachel Cawan said. “Most importantly, however, there must be available other emotionally satisfying alternatives to child raising.”

The prevailing feminist interpretation of these population control programs was that they masqueraded as liberating family planning alternatives when, in fact, many of these women were being coerced or forced to stop having children.

The Young Lords Party was founded in 1960. The men who founded the organization had a series of objectives including self-determination for Puerto Rico, liberation for third-world people and, problematically, “Machismo must be revolutionary and not oppressive.”

Early in the party’s history, the men in the movement did not listen to women’s ideas and concerns during meetings. These women were limited to essentially being glorified secretaries for the party according to a November 11, 1970 New York Times article.

The women in the movement soon tired of this dynamic and demanded to be taken seriously – and they succeeded. Several women were able to assume leadership positions in the party and the pillar relating to machismo was changed to one supporting equality for women. However, this victory did not mean women were automatically able to achieve true political and social equality within the party or on a larger scale.

In a subsequent issue of “Off Our Backs,” a black/Native American woman wrote a response to Burning Cloud’s letter, which had also said black people should support Native Americans’ issues, saying that: “There is a need for Dialogue, a conversation, between Indian people and Black people…We have been divided in order to be conquered, even though for many, our blood flows together.”

A theme that emerges again and again when studying the second-wave of the feminist movement is that by separating women into sects with seemingly irreconcilable differences, men have managed to prevent them from forming a powerful united front capable of combatting not only sexism, but racism and other social ills that afflict them.

-Anna Zarra Aldrich