Viewing a newspaper issue in the digital repository

Have you ever wondered when the first female editor-in-chief of the UConn newspaper was elected? Or wanted to examine student reactions to the attack on Pearl Harbor? Have you ever desperately needed to know the time and location of the Philosophy Club meeting on November 28, 1945? Thanks to an ongoing project here at Archives & Special Collections, the answers to these and other questions concerning campus history will soon be just a few clicks away. Several staff members, myself included, have been working since last summer on uploading past issues of the campus newspaper, from its inception in 1896 until 1990, to the Archives’ digital repository, a component of the Connecticut Digital Archive (CTDA).

To date, everything up to the 1942-1943 school year has been completed, as well as some years in the 1970s and late 1980s. Once uploaded, every issue becomes a permanent digital object that is searchable within the repository. Associated metadata includes publication date, editor, genre, and, when applicable, a short description that lists any errors particular to that issue (i.e. a mislabeled volume or issue number or date.) Users can conduct term searches within each issue, and there’s also the option to download and print a PDF version.

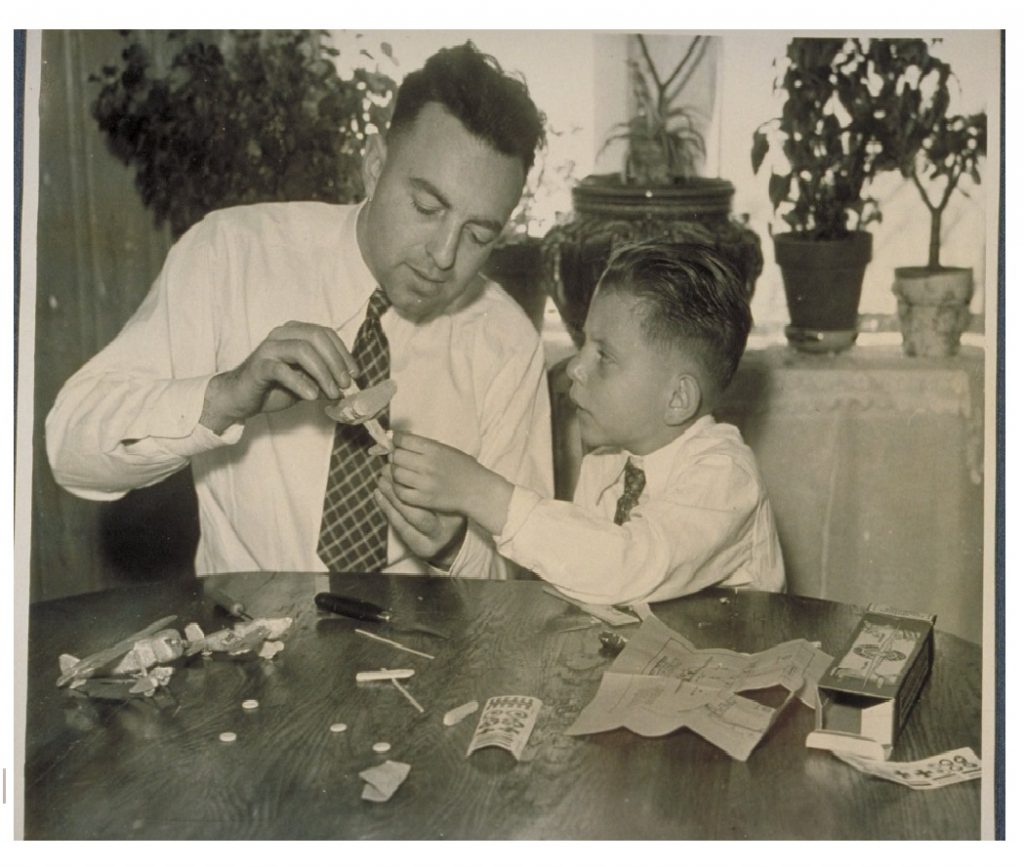

Prior to this project, access to most of the student newspaper archive was available only through the use of paper copies, like this one from 1940

Want to check out what we’ve completed so far? Visit the digital repository here.

Access to UConn’s student newspaper archive, in both physical and digital form, is relatively old news (pun intended.) Researchers who visit Archives & Special Collections have been able to examine bound volumes or microfilm reels for years, and the UConn Digital Commons has offered online access to some copies of the newspaper since early 2012. Frequent use and the passage of time, however, have begun to show their effects on both the physical copies and the microfilm, and although plans were made to make all issues available online through the Digital Commons by the end of 2012, the project was never completed. Finally having the collection completely digitized will address these concerns and essentially make the newspaper a “self-serve” resource, available at any time and from anywhere.

Completing the project is no small task, in part because there is so much material to process. For the paper’s first eighteen years, for example, it was published monthly during the school year with an occasional summer issue. That works out to approximately 170 issues produced for the years 1896-1914. At an average of 20-25 pages per issue (although some, like the Commencement Issue, ran much longer), the total number of pages is more than 4,000! The numbers only increase as the years progress and the paper becomes a semi-monthly, weekly, biweekly, and finally a daily in 1953.

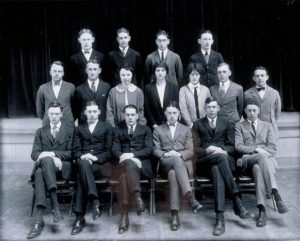

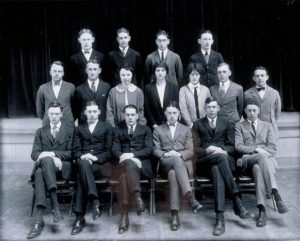

Editorial staff, Connecticut Campus, 1924

Another challenge has been tracking the changes undergone by the paper to ensure that the proper metadata is created and recorded for each individual issue. Just as the university has changed its official name several times over the course of its existence, so too has the campus newspaper gone by a number of different titles: the S.A.C. Lookout (1896-1899); the C.A.C. Lookout/Lookout (1899-1914); The Connecticut Campus and Lookout (1914-1917); the Connecticut Campus (1917-1955); the Connecticut Daily Campus (1955-1984); and finally the Daily Campus (1984-Present). There is also the Connecticut Scampus, an annual satirical issue first published in the 1920s. In addition, a new editor-in-chief was elected at least annually, and sometimes more frequently than that.

Luckily, the necessary groundwork had already been completed before we began the project. Realizing the historical significance of the newspaper, the UConn Libraries funded the scanning of the entire collection onto microfilm in the early 1990s. The Library again offered its support in 2012 when that microfilm was scanned and .txt, .jp2, and .pdf files were created for each individual page. It was from this cache of digital images that the Digital Commons issues were produced, and it is from there that we’ve been doing the majority of our work, grouping the individual pages into zip files (each one representing a single issue), ingesting them into the repository, and then adding the necessary metadata and PDF files.

Quality control is an important step throughout this process. The editors of yesteryear were far from perfect, and there are plenty of instances where volume and/or issue numbers are mislabeled and page numbers are out of order (or omitted entirely.) There are also errors from the microfilm scanning that need to be accounted for, like removing duplicates resulting from the same page being scanned more than once.

Challenges notwithstanding, progress has been steady, and we are looking forward to completing our work. In its entirety, the newspaper represents an integral part of UConn’s historical record, and is an ideal complement to the several excellent histories of the university that have been written (the out-of-print Connecticut Agricultural College: A History by Walter Stemmons, Bruce Stave’s Red Brick in the Land of Steady Habits, and Mark J. Roy’s University of Connecticut) which, owing to limitations of space and other factors, can never hope to include everything. When finished, the online archive will span more than a century and include thousands of pages. In using it, researchers will be given a unique perspective into the everyday nuances of campus life, and the reactions of students, staff, and the Storrs community to events, both major and mundane, that affected the campus, the nation, and the world.

A Brief History of the Student Newspaper:

1896 — Students of the Storrs Agricultural College establish a student newspaper, the S.A.C. Lookout. It begins as a monthly, and the first issue is published on May 11, 1896. The cost of a subscription? 50 cents a year, paid in advance.

1899 — The school is re-named Connecticut Agricultural College, and the paper becomes The C.A.C. Lookout.

1902 — The paper transitions to the simpler title the Lookout.

1914 — The paper changes its name to the Connecticut Campus and Lookout, and is published semi-monthly during the college year. It also takes on the standard newspaper format.

1917 — The paper simplifies its name to the Connecticut Campus beginning with the October 30, 1917 issue.

1919 — The paper begins publishing weekly with the October 3, 1919 issue.

1942 — The Connecticut Campus is published semi-weekly, on Tuesdays and Fridays. It will revert to a weekly two years later.

1946 — The paper again becomes a semi-weekly.

1950 — The paper is published three times a week.

1953 — Beginning with the September 21, 1953 issue, the Connecticut Campus becomes a daily.

1955 — The paper is renamed the Connecticut Daily Campus, and is published every weekday morning.

1984 — The school paper again simplifies its name, becoming the Daily Campus.

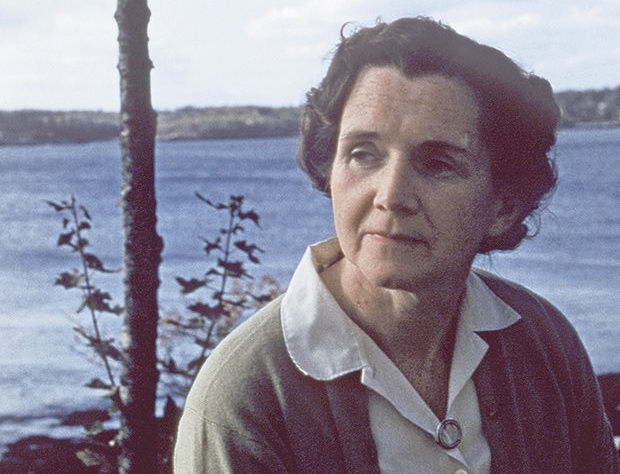

Rachel Carson, a new documentary film produced for the PBS series American Experience, is now available to watch online marking its debut broadcast on CPTV Connecticut public television.

Rachel Carson, a new documentary film produced for the PBS series American Experience, is now available to watch online marking its debut broadcast on CPTV Connecticut public television.

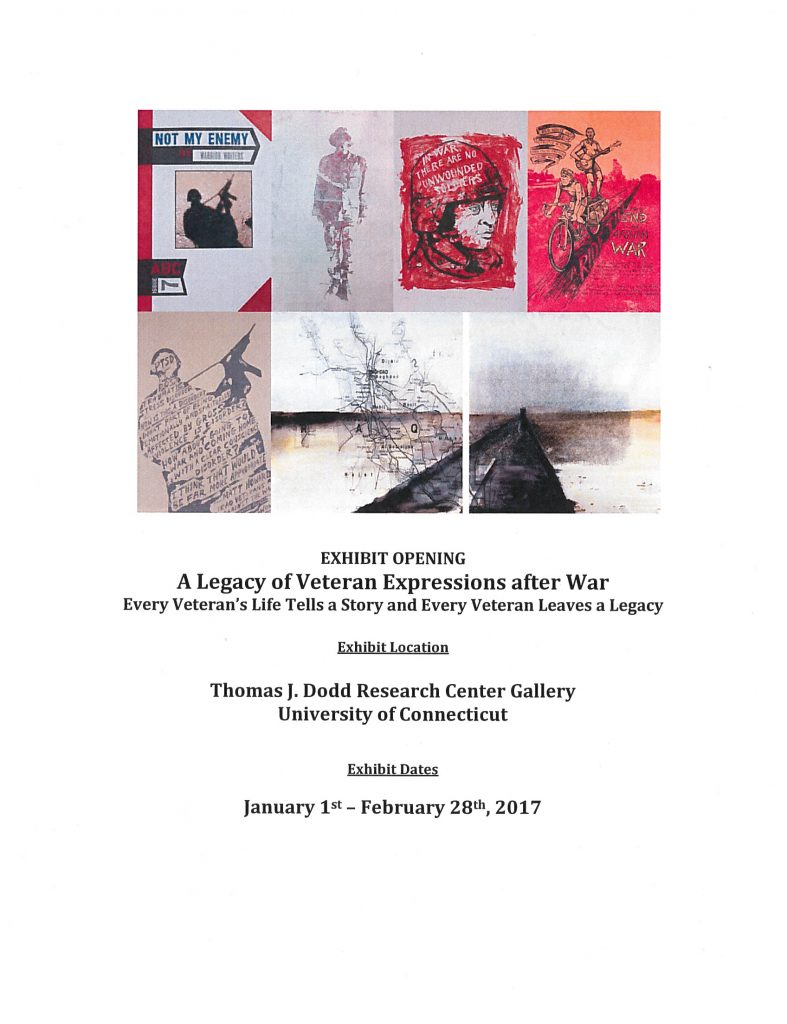

A correlating exhibition will be on display this spring in the hallway of the Dodd Center featuring photographic prints and oral histories of veteran’s from the Balkans conflict. Materials featured will be products of Robin’s photographic work and Jordan’s PhD research.

A correlating exhibition will be on display this spring in the hallway of the Dodd Center featuring photographic prints and oral histories of veteran’s from the Balkans conflict. Materials featured will be products of Robin’s photographic work and Jordan’s PhD research.