[slideshow_deploy id=’8928′]

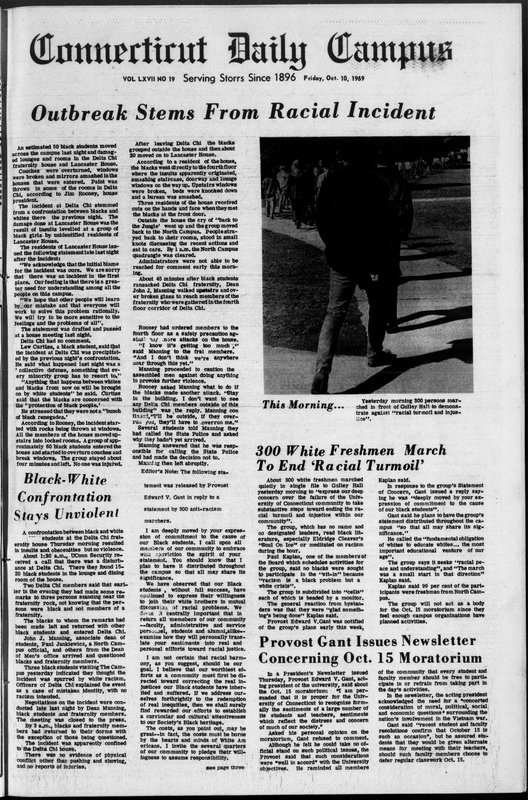

Near the center of the University of Connecticut

campus sits Hawley Armory, one of many oblong brick buildings. Built in 1915

and named after Willis Nichols Hawley, a UConn graduate who died of yellow

fever in the Spanish-American War, the armory has long served as a site for athletic

events, campus gatherings, and military exercises.

Yet as the historian Jeremy Brecher reminds us, sturdy

brick-buildings like Hawley Armory once appeared across the United States for another

purpose. They were designed to help defend the country, though not from distant

enemies but rather disturbances at home.

In the late nineteenth century, working people across

the country began to organize and agitate for higher wages, improved working

conditions, and a better quality of life. In these efforts, their key weapon

was the strike—the mass refusal to work. But capitalists and their political

allies had weapons of their own, and they didn’t hesitate to use them.

During the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, for example,

when local police refused to break up strikes, governors called in state

militias to do it for them. In these grisly skirmishes, armories proved useful

to government officials intent on breaking the power of workers. Even though

the Great Railroad Strike ended in failure, labor militancy continued in the

following decades, and the strike remained an essential tactic for workers.

As a leading industrial state, Connecticut has been

home to a fair share of labor unrest, much of it well documented in the

business and labor collections held by Archives & Special Collections.

One early example was the 1935 strike of 1,000 workers

at the Colt Patent Fire-Arms Manufacturing Company located along the

Connecticut River in Hartford. In the middle of the Great Depression, workers

routinely used work stoppages and picket lines to improve their working

conditions. And the workers at the Colt plant had good reason to strike. As one

striking worker, Leo LaForge, later recounted, “There was, in them days, no

holidays, no vacation, no sick days, no time and a half.”

The strike was a raucous affair, involving violence

and intimidation against workers, as well as an attempted bombing of the plant

manager’s home. Students from Yale and Wesleyan University even joined the

picket lines. Yet despite new laws protecting collective bargaining, the

company refused to negotiate with the workers and the strike was eventually

called off after a few weeks.

Workers at the Pratt and Whitney Division of the

Niles-Bement-Pond Company had greater success when they went on strike in 1946.

Organized by Unity Lodge 251 of the United Electrical, Radio and Machine

Workers of America, several thousand workers refused to work in an effort to

achieve higher wages. They aimed to raise their pay 18 ½ cents an hour, equal

to industry-wide rates. The company’s president, Charles W. Deeds, rejected the

worker’s demands, citing labor costs and supply shortages left over from World

War II.

But the striking workers had the wind at their backs.

In the years 1945-1946, the United States saw the largest strike wave in the

nation’s history. In 1946 alone, as many as four million workers walked off the

job. Despite concerted opposition from management, and tensions with local authorities,

thousands of Pratt & Whitney workers led mass pickets at the plant. After

twenty-one weeks, the company eventually settled, agreeing to a 12-cent raise.

The years after the Pratt & Whitney strike saw

significant improvements in the lives of American workers. Between 1947 and

1973, the working-class standard of living nearly doubled, and much of that

growth owed to the strength of organized labor. Yet the heyday of the

labor-management accord would not last long. Organized labor’s fortunes began to

wane as early as the late 1960s.

In 1967, for example, 100 workers at the Sessions

Clock Company in Bristol, Connecticut, voted to go on strike. Through their

union, Local 261 of the International Union of Electrical, Radio, and Machine

Workers, the workers at Sessions, many of them women, sought a 20-cent pay

increase. The company response was all too familiar. Picketing workers were

beaten at one point during the strike, sending one union organizer, James

Ingalls, to the hospital.

After nine weeks, the union accepted a 10-cent pay

increase and the workers returned to the factory. Despite the measured success,

the writing was on the wall: organized labor was in decline. Only a few years

later, the same union representing workers at the Sessions Clock Company was

lobbying members of Congress to increase worker protections. Foreign

competition combined with laws allowing corporations to easily move production

was battering once-thriving union towns. Rather than face strikes, companies

closed plants and moved them to areas with low taxes, low wages, and laws that

made it difficult to unionize.

Since the 1970s, the declining fortunes of organized

labor has been a key feature of American life. But this trend may soon be

changing. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018 saw more work

stoppages than at any time since 1986. Either way, there’s no better time to

explore the exciting history of strikes in Connecticut, and no better place to

do it than Archives & Special Collections at the University of Connecticut.

Among the relevant collections are:

Henry Stieg Collection of the Pratt & Whitney Company The collection comprises materials gathered by Henry R. Stieg, a master gage inspector at the Pratt & Whitney Division of the Niles-Bement-Pond Company from 1940 to 1973 and departmental steward in the Unity Lodge Local 251 of the United Electrical, Radio & Machine Workers and, after 1948, Unity Lodge, Local 405 of the United Automobile, Aircraft and Agricultural Implement Workers of America, CIO. The materials include publications, newsletters, flyers, and memoranda related to the company and unions, including the 1946 strike. They also contain drawings and machine plans, reports and maps, correspondence, contract proposals, as well as other union-related material, such as work agreements, job evaluations, newspaper clippings, and pamphlets. The finding aid can be found here: https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/679

James A. Ingalls Papers The papers comprise materials generated and gathered by James A. Ingalls when he served as a Field Representative of the International Union of Electrical, Radio & Machine Workers, AFL-CIO. They include contracts, correspondence, legal records, financial records, and newspaper clippings. They also contain notes from when Ingalls represented Connecticut local chapters to negotiate contracts, resolve strikes and lockouts, and develop collective bargaining agreements, pension plans, and compensation and health benefits packages. Included in the papers is material on the 1967 strike at the Sessions Clock Company. The finding aid can be found here: https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/454

Nicholas J. Tomassetti Papers Nicholas J. Tomassetti was a labor organizer associated with the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers Union, as well as a Democratic representative to the Connecticut General Assembly. The papers document Tomassetti’s labor activities and involvement in the United Electrical, Radio & Machine Workers Union (UE) and include correspondence, reports, administrative and legal records, strike and negotiation materials, directories, minutes, publications, scrapbooks, photographs, and newspaper clippings. The finding aid can be found here: https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/705

Ralph J. Pancallo Papers Ralph Pancallo was a long-standing member of the International Typographical Union (now the Communications Workers of America). Pancallo also served as vice president of the Connecticut State Labor Council, secretary and president of the New Britain Central Labor Council, and as both president and treasurer of the New Britain Typographical Union #679 (now the Connecticut Typographical Union #679). The papers comprise materials collected by Pancallo, including union meeting minutes, financial ledgers, printed materials, correspondence, clippings, convention reports, programs, and films. Other materials include publications from a variety of local typographical unions, as well as the AFL-CIO. The finding aid can be found at https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/584

University of Connecticut, Center for Oral History Interviews Collection The collection comprises interview transcripts conducted by the University of Connecticut Center for Oral History, and individuals and programs associated with the Center. The Center began life as the Oral History Project in 1968 and after expanding over the 1970s was made a center by the UConn Board of Trustees in 1981. The collection includes the transcripts of interviews with workers who participated in the 1935 Colt strike, along with other collections focused on labor and industry in Connecticut. The finding aid can be found at https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/984 and digitized material can be found here: http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:19840025

We invite you to view these collections in the reading room at Archives & Special Collections. Our staff is happy to assist you in accessing these and other collections in the archives.

This post was written by Shaine Scarminach, a UConn History Ph.D candidate who is a student assistant in Archives & Special Collections.