IT’S ALL ABOUT STORY

When I began my research on the relationship between text and art in picture books, I was hoping to uncover the “secrets” of some of the author/illustrators whose work is housed in the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection archives. I studied a number of different collections, and I am leaving with many ideas of how to improve my craft. My writing process will now include consistent creation of picture book mock-ups (dummies), and I have a greater understanding of specific approaches to writing text that “leaves room” for an illustrator.

Interestingly, though, I conclude my research with one overriding thought. The very best picture books—whether written by an author and illustrated by someone else, or created by an author/illustrator—have at their heart a good story. So authors and author/illustrators have equal opportunity to begin their creative picture book journeys in the same place – at the deep well of great stories we each have within us, stories about memorable characters who change as they solve problems or encounter conflict.

Revising text plays an important role in refining such stories (although the author/illustrator also revises art to strengthen his or her work). But always, it is the story that is the starting point. I will share a fine example:

WINGS: A TALE OF TWO CHICKENSby James Marshall

The kernel of this story appears to have been James Marshall’s vision of an old, hungry fox trying to outwit foolish fowl to find a meal. A preliminary sketch shows the disguised fox tricking a chicken into a bag.

Marshall, James. WINGS: A Tale of Two Chickens. Sketch of fox bagging chicken. Series I, Box 12: Folder 217 of James Marshall Papers. All rights reserved. No reproduction of any kind allowed.

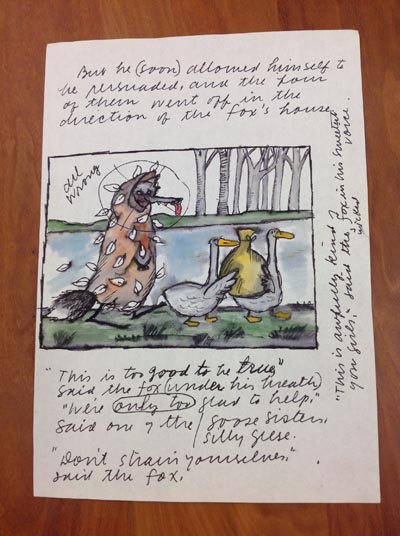

When two silly geese sisters offer to help transport the heavy bag, the fox says, “This is too good to be true.”

Marshall, James. WINGS: A Tale of Two Chickens. Sketch of fox and geese, in Series I, Box 12: Folder 217 of James Marshall Papers. All rights reserved. No reproduction of any kind allowed.

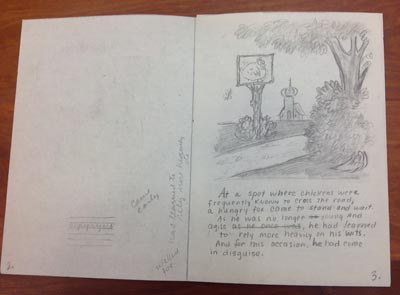

An incomplete, early dummy of this story line shows a “chicken crossing” sign and a fox hiding behind a tree:

Marshall, James. WINGS: A Tale of Two Chickens. Untitled, incomplete dummy, p.3. Series I, Box 12: Folder 216 of James Marshall Papers. All rights reserved. No reproduction of any kind allowed.

The text on this opening page reads:

At a spot where chickens were

frequently known to cross the road,

a hungry fox came to stand and wait.

As he was no longer young

and agile, he had learned

to rely more heavily on his wits.

And for this occasion, he had come

in disguise.

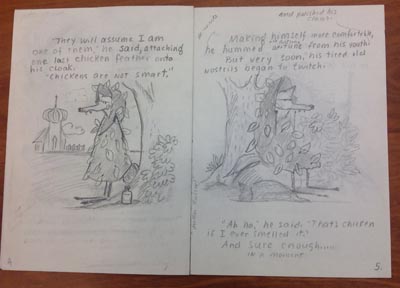

The focus on the fox as protagonist continues in this version of the story, where we see the fox waiting in his chicken disguise:

Marshall, James. WINGS: A Tale of Two Chickens. Untitled, incomplete dummy, pp. 4–5. Series I, Box 12: Folder 216 of James Marshall Papers. All rights reserved. No reproduction of any kind allowed.

However, it appears that James Marshall soon decided he could tell a better story from another angle (the incomplete dummy ends on page 6).

The first complete dummy reveals that the plot has taken a very different turn. Marshall completely switches the beginning to focus on two chickens who are close friends (maybe the two silly goose sisters in his preliminary sketches inspired this turn); the fox still plays a key role, but he is no longer a protagonist.

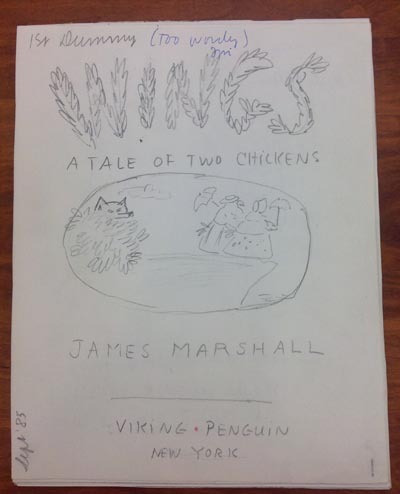

The title of the book, shown on this hand-drawn dummy cover, is:

WINGS

A TALE OF TWO CHICKENS

Marshall, James. WINGS: A Tale of Two Chickens. Sept. ’85 dummy, cover. Series I, Box 12: Folder 215 of James Marshall Papers. All rights reserved. No reproduction of any kind allowed.

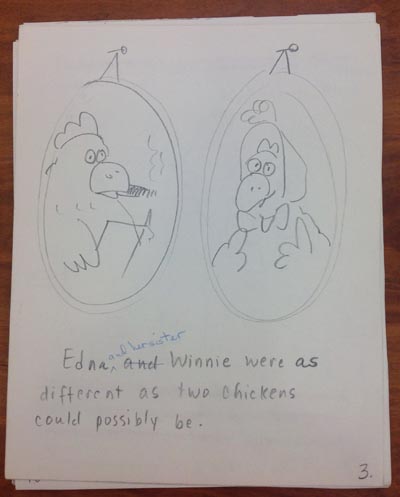

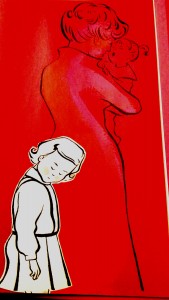

Two chickens, with parasols, stand side by side at the edge of a precipice, and a fox hides in bushes in the background. The reader immediately knows this is a story of friendship and danger, and the first line of the dummy introduces Edna and Winnie (Harriet and Winnie in the published version) who are “as different as two chickens could possibly be.”

Marshall, James. WINGS: A Tale of Two Chickens. Sept. ’85 dummy, p.3. Series I, Box 12: Folder 215 of James Marshall Papers. All rights reserved. No reproduction of any kind allowed.

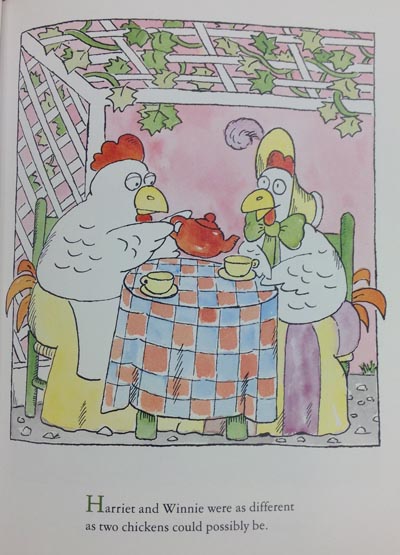

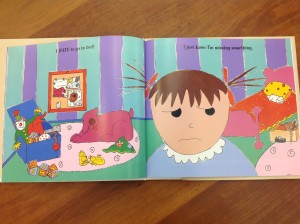

The first page in the published book shows the two good friends sharing tea:

Marshall, James. WINGS: A Tale of Two Chickens (New York: Viking Kestrel, 3. Photo taken from CLC C38, Archives and Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Edna (Harriet) loves reading and hobbies. Winnie would “rather swat flies than read” and is easily bored. Marshall sets up this pair of friends immediately, and when the disguised fox appears and offers foolish Winnie a ride in a hot air balloon, Edna (Harriet) fears for Winnie’s safety. A whole series of events follows, with the dastardly fox ultimately outwitted by Harriet, disguised as a fox. The plot twists and understated text are hilarious, and readers cheer for the friends right up until the closing page, when Harriet tucks Winnie into bed.

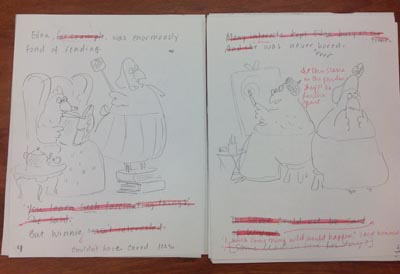

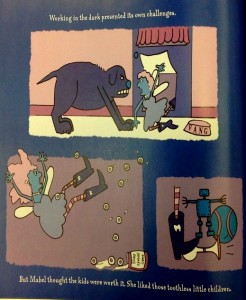

Marshall revised and refined his text zealously—on the top of the cover of his Sept. ‘85 draft (see above) there is a parenthetical note he wrote to himself in blue pen, “too wordy.” The following pages are replete with red pencil cross outs and revisions, to pare the text of this story. For example:

Marshall, James. WINGS: A Tale of Two Chickens. Sept. ’85 dummy, pp.4–5. Series I, Box 12: Folder 215 of James Marshall Papers. All rights reserved. No reproduction of any kind allowed.

Marshall clearly thought about pacing and forward movement as he revised. The above page 5 has a crossed-out, bracketed note he wrote to himself: [Some lead in here for story?]. He created that lead-in by penciling in the line spoken by Winnie just before the hot air balloon floats into the garden:

“I wish something wild would happen,” said Winnie.

And the story takes off from there. James Marshall continued to revise his text to strengthen his story and characters throughout that first complete dummy, a second dummy, a final dummy, and various pages of text revised within some of his sketchbooks.

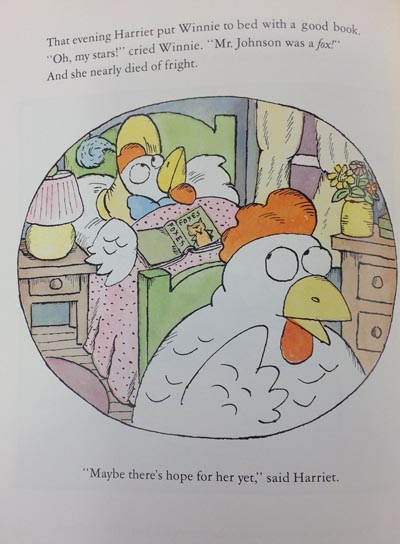

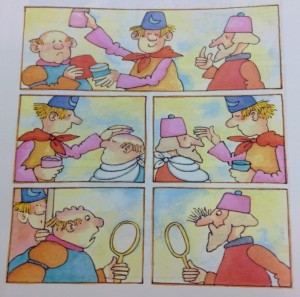

As for character growth? Winnie is at last reading a book— about foxes. She exclaims, “Mr. Johnson was a fox!” Meanwhile, Harriet hasn’t given up on her friend. “Maybe there’s hope for her yet,” said Harriet.

Marshall, James. WINGS: A Tale of Two Chickens (New York: Viking Kestrel, 32. Photo taken from CLC C38, Archives and Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

INSPIRATION

I am concluding my research at the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection greatly inspired. For several months, I have been working on a picture book, Chipmunk and Robin, about two close friends who are very different. As I polish and revise this story, I will draw on my new knowledge of how some of the best picture book story tellers (who happen to also be illustrators) craft character, crisis, and resolution into a full and satisfying story arc. Even though it will be a lot of work, the real secret is—it will be a lot of fun!