This is the first of a series of blog posts by Nick Hurley, who earned a M.A. in History at UConn and previously worked as Research Services Assistant at Archives & Special Collections.

How time flies!

Since its founding in 1916, the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (better known as ROTC) has become a fixture on many U.S. college campuses, and UConn is no exception. More than two hundred Huskies are currently serving as Cadets in either the Nathan Hale Battalion, the Army’s only ROTC unit in Connecticut, or Air Force ROTC Detachment 115, “Snake Eyes Five”.

I spent four years in the Nathan Hale Battalion, from 2009-2013, reaching the rank of Cadet Captain and eventually commissioning as a Field Artillery officer. Given my personal connection to UConn and the military (not to mention my love of all things history), I thought it would be appropriate, especially because ROTC is turning 100 this year, to examine the long and fascinating story of military training at UConn.

To do so, there was no better starting point than the holdings here at Archives and Special Collections. Series VI of the University of Connecticut Photograph Collection contains three boxes of photographic prints which document all aspects of Cadet life from the early 1900’s to the present, including training exercises, social events, and inspections. There are also numerous portraits of Cadets, Instructors, the Cadet Band, and the Color Guard. A small number of these photographs have been uploaded to our digital repository. Physical artifacts are contained in the UConn Memorabilia Collection, including a dress uniform jacket from the late 1930’s and a unit patch dated 1918, and general administrative files from both Army and Air Force ROTC can be found in the UConn Office of Public Information (OPI) Records.

CAC Cadet Band, circa 1907. Note the blue uniforms and collar insignia marked “C.A.C”. These would be replaced by Army green uniforms and ROTC insignia beginning in 1917.

Though this year marks the centenary of ROTC, UConn’s affiliation with military training in general dates back to 1893, when the Storrs Agricultural School was renamed the Storrs Agricultural College. Along with the name change came the conferral of land-grant status to the university. Under the terms of the Morrill Act of 1862, land-grant colleges received federal land and assistance in return for offering academic programs in agriculture, engineering, and military tactics. The administration at Storrs deemed it appropriate to not only offer military classes, but make them mandatory, and thereafter every male student who enrolled at the school received instruction under the direction of a newly-hired Professor of Military Science. This training was not intended to produce commissioned officers, however, and students incurred no military obligation upon graduating from Storrs Agricultural College, which in 1899 became the Connecticut Agricultural College (CAC).

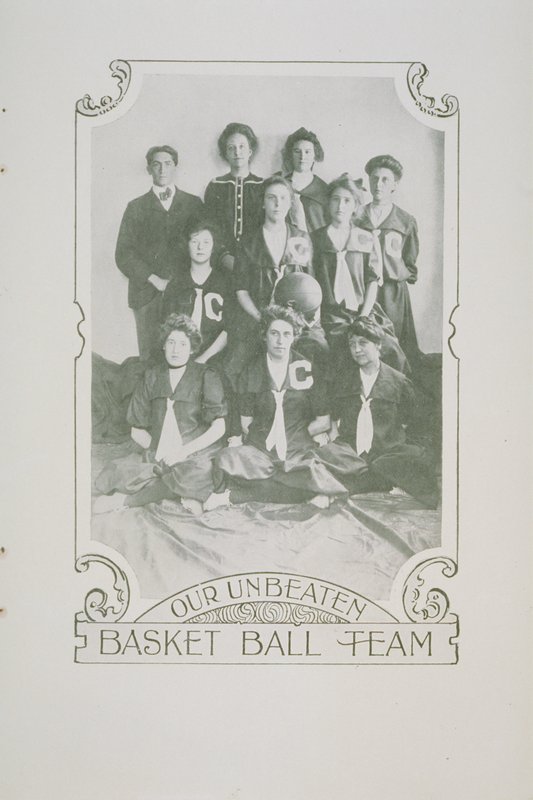

Members of the CAC Cadet Battalion, 1905. The officer in the second row, fourth from left is Lieutenant E. R. Bennett, Commandant of Cadets

The roots of what we now know as ROTC can be traced back to the National Defense Act of 1916. Among its other provisions, it provided federal assistance for the establishment of officer training programs at a number of universities. UConn was one such institution, and on November 1st, 1916, War Department Bulletin No. 48 announced the creation of “an Infantry unit of the Senior Division, Reserve Officers’ Training Corps” at Storrs.

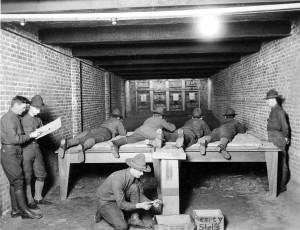

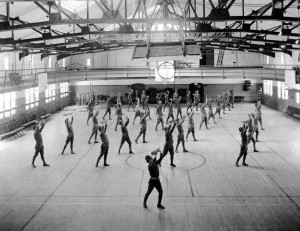

The introduction of ROTC brought both change and continuity. Activities like the Cadet Band and Color Guard remained integral components of ROTC life, and drill continued to be held in Hawley

Armory, named for SAC graduate Willis Nichols Hawley following his death during the Spanish-American War. Completed in 1915, the facility also housed facilities for athletics, an auditorium, and even a rifle range in the basement. (Today, the armory continues to serve as a supply room and exercise area for UConn Cadets—but, not surprisingly, the rifle range is no more!)

Still, no one could deny that a significant shift in military training at Storrs had occurred. An article in the April 30, 1917 edition of the Connecticut Campus noted that:

A young man now entering the Connecticut Agricultural College, if a citizen of the United States and physically fit, becomes a member of the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps. Without cost he is furnished with rifle, uniform and necessary equipment. For two years he devotes three hours a week to military training under the prescribed course. At the end of the two years, if he so elects, and if he is recommended by the President of the college and the Commandant he may sign an agreement to devote five hours a week to the advanced course in Military Training for the remaining two years of the college course…a graduate of the college who has completed the advance course is eligible for appointment by the President of the United States as Second Lieutenant in the regular army for a period of six months with pay at $100 per month and to a commission in the Officers’ Reserve Corps.

There were more visible changes as well; students no longer wore the Cadet blue uniform, exchanging them for Army greens with an olive drab cuff insignia emblazoned with the letters “U.S.” and “R.O.T.C.” In addition, new rifles and other equipment were soon delivered to campus courtesy of the War Department, and Lieutenant Frank R. Sessions arrived in October of 1917 to replace Captain Charles Amory as Commandant. The arrival of Lieutenant Sessions was not a moment too soon. War had been declared that April, and many male students had already left campus for the battlefields of France and Belgium. Of the nearly six hundred CAC students and alumni who would ultimately serve in the Great War, at least seven would not live to see the armistice declared in November of 1918.

Those who remained in Storrs trained with a new sense of purpose and urgency. By the summer of 1918, however, the Cadet contingent at CAC was overshadowed by a new government-initiated program: the Students’ Army Training Corps (SATC). The Corps essentially placed participating universities on a war footing; students and staff alike were inducted into the military, and remained on campus for instruction in trades and skills deemed vital to the war effort. At the completion of such courses, the intent was to assign graduates to officers’ school, regular duty as enlisted men, or further technical training. Some four hundred CAC men had signed up by the time the short-lived program was disbanded in December of 1918. Following a brief lull, ROTC was reinstated the following January with the arrival of Captain Claude E. Cranston as the new Professor of Military Science. By the end of that year, Cadet training had more or less returned to what it had been before the introduction of the SATC.

ROTC Cadets standby for inspection of their encampments and equipment, 1919. Hawley Armory and Koons Hall are in the background. Oak Hall now stands on the site of the parade field

Notwithstanding a brief suspension during the First World War, then, ROTC had by 1920 established itself as a fixture on the Storrs campus. The future of the program would be anything but tranquil, however, as the remainder of the twentieth century would prove eventful, both on campus and abroad. In my next post, we’ll look at the debates over compulsory participation in ROTC. Stay tuned!

–Nick Hurley

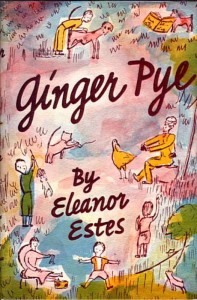

Eleanor Estes (1906-1988) was one of the most highly acclaimed children’s authors of the mid-twentieth century. I grew up reading her classic stories about the Moffats and the Pyes, and her hauntingly beautiful, iconic tale of childhood bullying, The Hundred Dresses. Born in West Haven, Connecticut, and launching her career as a children’s librarian in the New Haven Free Public Library, Estes reaped three Newbery Honors in three successive years for The Middle Moffat (1942), Rufus M (1943), and The Hundred Dresses (1944) and finally went on to win the John Newbery Medal, awarded for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children, for Ginger Pye (published in 1951), followed by a sequel, Pinky Pye, in 1958. Praised for her microscopically careful observation of the inner life of children, she’s invariably heralded as a leading figure in any discussion of the genre of the “family story.” But she’s also been criticized for what is taken to be her failed attempts, in her later books, to provide more of a sustained and satisfying plot.

Eleanor Estes (1906-1988) was one of the most highly acclaimed children’s authors of the mid-twentieth century. I grew up reading her classic stories about the Moffats and the Pyes, and her hauntingly beautiful, iconic tale of childhood bullying, The Hundred Dresses. Born in West Haven, Connecticut, and launching her career as a children’s librarian in the New Haven Free Public Library, Estes reaped three Newbery Honors in three successive years for The Middle Moffat (1942), Rufus M (1943), and The Hundred Dresses (1944) and finally went on to win the John Newbery Medal, awarded for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children, for Ginger Pye (published in 1951), followed by a sequel, Pinky Pye, in 1958. Praised for her microscopically careful observation of the inner life of children, she’s invariably heralded as a leading figure in any discussion of the genre of the “family story.” But she’s also been criticized for what is taken to be her failed attempts, in her later books, to provide more of a sustained and satisfying plot. Thus, John Rowe Townsend complains that, in contrast to the Moffat family stories, “[i]n Ginger Pye . . . there are plots of mystery and detection which call for a dramatic build-up, a logical progression toward climax, which the author is infuriatingly unable or unwilling to provide.” [1] Virginia L. Wolf writes that while Ginger Pye “more effectively focuses on a problem and builds suspense than do any of the Moffat books, [i]t does not, however, as the critics have charged, offer the tightly constructed plot of a successful mystery. . . .” [2]

Thus, John Rowe Townsend complains that, in contrast to the Moffat family stories, “[i]n Ginger Pye . . . there are plots of mystery and detection which call for a dramatic build-up, a logical progression toward climax, which the author is infuriatingly unable or unwilling to provide.” [1] Virginia L. Wolf writes that while Ginger Pye “more effectively focuses on a problem and builds suspense than do any of the Moffat books, [i]t does not, however, as the critics have charged, offer the tightly constructed plot of a successful mystery. . . .” [2]

danger, and to center her story less on what happens than on children’s quiet and wry observations in response.

danger, and to center her story less on what happens than on children’s quiet and wry observations in response.